Need for speed: Caster Semenya

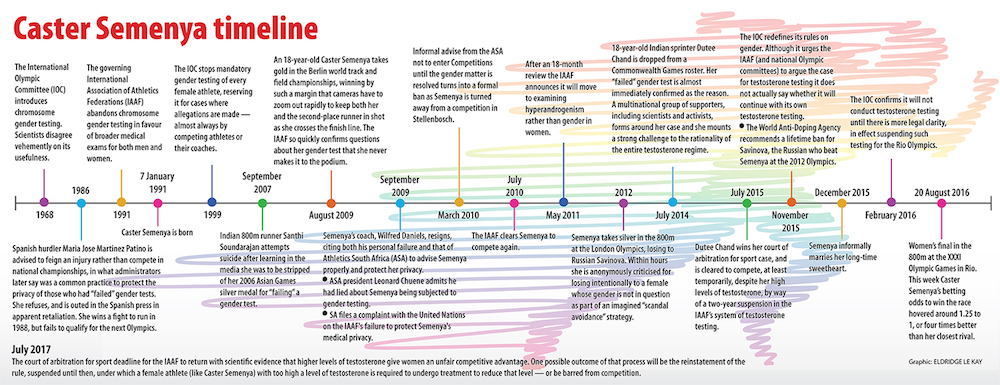

When Caster Semenya won the world championship 800m final in Berlin in 2009, she was rewarded with a ban on competing on top of a crushing invasion of her medical privacy.

The firestorm that started as soon as she crossed the finish line consumed sports administration careers like kindling and sparked a number of court cases and diplomatic fights.

If Semenya wins the 800m Olympic gold in Rio de Janeiro this August, everything suggests that the furore will be worse. At stake this time is not one medal but the future of women’s sports – and the money and prestige that depend on it – in a world that is rapidly leaving binary sexuality behind, with all the political and religious turmoil brought about by that change.

If she performs well enough Semenya, who has sought as quiet a life as an athlete of her stature can reasonably aspire to, may become the biggest story of an Olympic Games also featuring the Zika virus and financial calamity. If she performs poorly, she will be accused of throwing the race for political reasons.

But large as those scenarios loom, the South African organisations that failed Semenya so spectacularly in 2009 stand proudly unprepared for what is to come.

“For us it is not an issue,” said Athletics South Africa (ASA) president Aleck Skhosana on preparations for any fallout around Semenya’s performance. “There is nothing to worry about.”

“No need to,” said Tubby Reddy, chief executive of local Olympic governing body Sascoc and the diplomatic chief of the South African team going to Rio, on whether his organisation had taken any pre-emptive measures. Questions on how Sascoc planned to deal with controversy were not applicable, he said.

In 2009 Sascoc decapitated ASA with suspensions because of its poor handling of the Semenya debacle.

On Thursday sports minister Fikile Mbalula said he could not “speak about what would not have happened”, but that he hoped South Africans would rally around Semenya: “Anything that seeks to undermine the standing of Caster [Semenya] I think is anti human rights and not worth promotion.”

Both the ASA and Sascoc said they had faith in the promises made by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to prevent a repeat of 2009, and to protect athletes such as Semenya from controversy.

The IAAF fought hard against challenges to the gender-testing regime under which Semenya would have competed in August, until they were temporarily struck down a year ago. After the IAAF lost, the IOC called on it to continue that fight.

But there will be “absolutely no debacle” this time, Sascoc’s Reddy told the Mail & Guardian.

Great odds

On Monday the two top American contenders for the 800m women’s event, Brenda Martinez and Alysia Montano, were knocked out of the competition by an on-track collision during their United States Olympic track and field trials event.

The 2012 Olympic champion, Mariya Savinova, along with many Russian compatriots, will not be at the Rio games thanks to a massive doping scandal.

That has left Semenya with bookmaker odds that will pay out only R12 for every R10 bet on her to win – two weeks before she even gets on a plane to Rio, and with all the dangers of the early rounds before her. A R10 bet to win on Semenya’s closest rival in the race placed on Wednesday, by contrast, would pay R80.

If Semenya does well, there will be questions about whether she should thank recent changes in sports law for her performance. If she fails to do well, especially while looking as though she is not straining, history suggests she will be accused of throwing the race for political reasons. And anyone else who stands out in the race for any reason will end up being compared with Semenya, because she is the athlete who has a history of questions regarding her gender.

“I would frankly be rather surprised if the winner of that race was someone who was competing with the typical testosterone level that a female carries,” said medical physicist Joanna Harper this week.

Harper is one of many who have been drawn into a debate around sex in sport that is already raging in athletics circles, and that already has Semenya at its centre.

Harper is better positioned to comment than most, as a transsexual who has researched transsexual performance in competitive sport – but everyone is being forced to come up with an opinion.

“I like Caster,” US runner Martinez told the cameras with a big smile before she was knocked out of the competition. “She’s been so nice to me. She does have an advantage though … Yeah, she’s different, but that’s not her fault though. I like her, I respect her, I do want to race her.”

More diplomatic contenders have simply batted away the question, at least in public and at least so far. Malicious rumour, so rife in competitive sport, suggests that any number of them would love to see the issue blow up. And the issue is this: how much credit for Semenya’s performance should go to a feisty young Indian runner who successfully challenged the status quo around gender testing?

Testosterone

Semenya’s return to world-beating form has become increasingly evident with the approach of the Rio Olympics, which, given the rate of attrition among athletes approaching their 30s, could be her last. She had been building towards such performances for 20 months, coach Jean Verster previously told the M&G.

“All kinds of people will always try to make publicity for themselves when it comes to high-profile athletes,” Verster said on speculation about Semenya’s testosterone levels. “Unfortunately, you are always going to get people like that.”

Semenya herself has also refused to comment on the speculation about her legal position, stressing that her focus was on training and her performance.

That has not stopped others from seeing more than just correlation between Semenya’s improved performance and a change in the legal status of testosterone.

“The change has happened for an obvious reason,” said sports science professor Ross Tucker in May on Semenya’s great race times, referring the Court of Arbitration for Sport’s ruling against the upper limit the IAAF had imposed on legal levels of testosterone for women.

Statistics suggest that there are any number of high-profile professional athletes who, biologically, do not fall easily into the male/female split used in sport. Most of them will never be identified thanks to medical privacy rules. Semenya is not among those.

“I have been subjected to unwarranted and invasive scrutiny of the most intimate and private details of my being,” Semenya said in a 2010 statement, after the IAAF confirmed she had been subjected to “gender verification testing” and that those tests had been not been immediately conclusive.

‘The conjecture is that she is intersex,” Harper puts it bluntly.

That conjecture, in turn, leads to the assumption that Semenya had higher than average levels of testosterone, and would have been obliged to seek medical treatment to bring those levels down to what the IAAF considered appropriate for women.

In July 2015, however, Indian sprinter Dutee Chand satisfied the Court of Arbitration for Sport that the IAAF’s testosterone rule was based on very dubious evidence. The rule was suspended for two years.

That, Tucker said, “cleared the way for Semenya, and at least a handful of others, to return to the advantages that this hormone clearly provides an individual”.

Legally, by the precedent accepted by the IOC, women with higher levels of testosterone are not considered to have an advantage over others. Scientifically the matter is in dispute; testosterone’s effects before birth are very different from its effects in adults, and those effects vary widely based on genetic factors still poorly understood. Factually, nothing is actually publicly known about Semenya’s medical status – but some things have come to be taken for granted.

“I know the IAAF pushed her to push her hormones down and whatnot with medication,” said Martinez.

The final assumption, then, is that when the IAAF stopped being able to demand such treatment, Semenya must have stopped her treatment. With direct information on her private medical affairs out of bounds, however, the assumption is being measured against her performance.

So if Semenya wins, at least some will credit testosterone. If she loses, though, testosterone will still get the blame.

When Semenya came in second in the 2012 Olympic 800m – losing to a now alleged drug cheat – she was accused of playing politics. Second place, some observers speculated, would lay to rest suggestions of an unfair hormonal advantage.

The suspicion did not dissipate, and even Semenya’s fans and supporters are prone to worry that she has intentionally underperformed.

“Caster, you have been quiet,” US doctoral student Eleni Schirmer wrote this week in an open letter to Semenya published by sports broadcaster ESPN. “Maybe you have been holding back, not wanting to show the world just how fast you can be. Perhaps you are scared that your victory will provoke accusations about your right to compete as a woman, provoke more interrogation of your body.”

Schirmer told Semenya she would be cheering for her, and to “run fast”.

The IAAF will have to present data-rich evidence to win reinstatement of the testosterone rule, but anecdotal though they are, Olympic performances will still be top of mind come July 2017, when the next major hearing on the issue is due.

In the time since 2009, many people have become better educated about the range of human gender and sexuality, Harper said. That may count for something. “I certainly hope [the debate] will be more civilised than the furore that erupted in 2009, but I guess one never knows,” she said.

In the same interval Semenya tentatively confirmed her informal wedding to a long-time, female partner, with a predictable response from the trollosphere.

But the ASA is not worried. “The best thing is that Caster is not stressed with this,” said Skhosana. “She is mentally equal to the task.”

Testosterone: Sometimes the genes are an unusual fit

Pick any athletic discipline and you’ll find men perform roughly a tenth better than women. That is why there must be a way to sort the men from the women, the likes of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) argues, just as boxers are divided into weight classes.

But as much as athletics craves a sharp delineation between men and women, science is unable to deliver. If anything, science continues to make the problem more tricky.

Sporting bodies first sought to distinguish men from women by way of genital exams, naturally administered only to women.

That approach was halted, not because of its fundamentally invasive and offensive nature but because science pointed out that the state of external genitalia makes little difference to what makes men faster and stronger. Though never cited as such, the relative ease of surgically altering external genitalia may also have weighed on the minds of sports administrators.

In the 1960s the sporting world turned to the far more palatable chromosome testing for gender determination, using a cheek-swab test. Even as it did so, science was there to point out that the idea was fundamentally daft. Most men do have XY chromosomes and most women have XX chromosomes, but that is only on average.

The World Health Organisation estimates that several people in every thousand have either just an X or just a Y sex chromosome, and some have three or more, making them XXY, or XYY or some other variant. That is before confounding factors such as androgen insensitivity syndrome, which can see a XY person – who would usually develop as a male – develop as a female instead, or the further confusion that androgen insensitivity has three recognised categories of effect. People outside the XY/XX divide are not typical, but then neither are professional athletes.

In Olympic sport chromosome testing was, on paper, replaced with the consideration of a range of factors. As a November 2015 consensus position by the International Olympic Committee shows, however, it all came down to testosterone, primarily a male hormone. By that consensus, anyone who transitions from female to male can compete with no restrictions.

Those who transition from male to female, though, are required to keep their levels of testosterone below a specified level, 10 nanomoles per litre in serum, with mandatory testing and a 12-month ban for drifting into “male” levels of testosterone. The same limit on testosterone was in place for women athletes in what the IAAF dubbed regulations on hyperandrogenism, adopting a term for a medical condition.

But in a complex ruling running to more than 160 pages, the Court of Arbitration for Sport in July 2015 suspended those regulations for lack of evidence in a matter brought by Indian athlete Dutee Chand.

Although evidence indicates that higher natural testosterone “may increase athletic performance”, the court said, it was “not satisfied that the degree of that advantage is more significant than the advantage derived from the numerous other variables which the parties acknowledge also affect female athletic performance: for example, nutrition, access to specialist training facilities and coaching, and other genetic and biological variations.

“Further evidence as to the quantitative relationship between androgen levels in hyperandrogenic females and increased athletic performance is therefore required,” the court said. – Phillip de Wet