The exhibition Henri Matisse: Rhythm and Meaning, which has opened in Jo’burg, gives us an idea of the ageing master’s last grand preoccupation and glorious breakthrough.

By the late 1930s, his drawing had become as simple and elegantly bold as grace can afford. On the other hand, his painting was growing ever more charged with brilliant blocks of colour. In fact, as he got older, Matisse is reported to have discovered to his regret that “my paintings and my drawing are growing in separate ways”.

One merely has to compare a number of his works hanging in the Standard Bank Art Gallery to see this neatly illustrated. There are two kinds of line portraits — one a bold line-drawing lithograph, titled Large Head, Katia, and another, a delicate etching, titled Portrait of a Martinican Woman. These can be compared with an oil painting, Woman in Blue Gandurah.

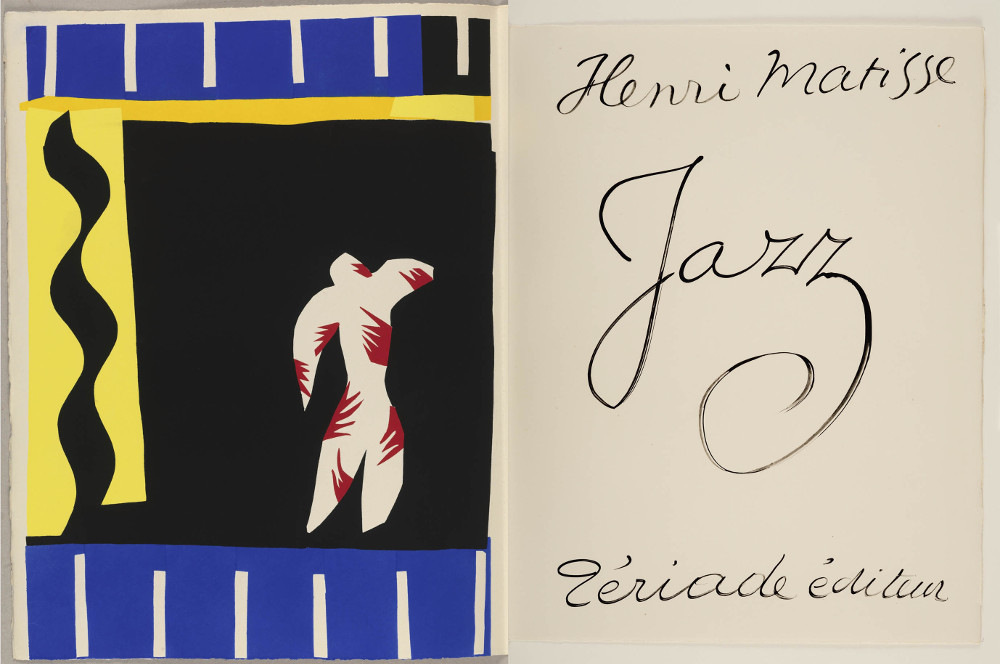

Hanging among the later style of paper cut-outs, one can see how the later works became a winning formal compromise. The myriad figures of the paper works are at once line-works and fields of colour. Matisse called this technique “drawing with scissors”.

A cut-out by Matisse is a drawing, painting and sculpture all at once. He found a method that could bridge the gap between his paintings and drawings, colour and line.

Matisse used the method of cutting coloured papers much earlier — in 1920 specifically — for his costume designs for Diaghilev’s ballet Le Chant du Rossignol.

But it was while working on the portfolio now on show that the penny dropped. To appreciate this, we must consider that Matisse was well into his 70s and recovering from cancer-related surgery that relegated him to a wheelchair. The resultant existential frustration make the glory of the cut-outs a defiant vignette of a grasp at vitality by a man with his own mortality in mind.

Le clown [The Clown] 1947. First plate of the book Jazz. Gouache stencil print on Arches paper 42 x 65cm. (Musée départemental Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis)

Matisse famously said: “Only what I created after the illness constitutes my real self: free, liberated.”

Cut-outs, so reminiscent of children’s books, are more than a beautiful solution by a painter who could no longer walk or use his easel. The cut-outs are the master’s clawing at the fading vestiges of creative vitality and striking gold.

As a technique, the cut-outs yielded three masterpieces: the dance mural in the Barnes building in Merion, Pennsylvania, the stained glass windows of the Dominican chapel in Venice, and Jazz, the artist book Matisse created at the prompting of his Parisian publisher, Tériade (Stratis Eleftheriades).

In about 1938, Tériade was exercising the idea of commissioning Matisse to do an illustrated book on the subject of the circus. He had already successfully published circus-related works by Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró and others. A selection from the resulting body of work gives the Matisse exhibition its verve.

The title of the exhibition may not be referencing Margret Stuffmann’s essay, Jazz: Rhythm and Meaning, but she is important because she can help us to understand the headspace of an old artist as he created what would become the world’s most famous artist booklet, Cirque, later renamed Jazz.

Stuffmann writes that, “as far as the title is concerned, the first idea was Cirque, and the notion of Jazz came up only as work progressed. Familiar as Matisse was with the United States, and much as he appreciated the clear light, crystalline look of the architecture and vitality of the country, Jazz is unlikely to refer just to individual experience, and is as unlikely to be meant solely as a visual equivalent of the American music that became equally fashionable in Paris from the 1920s.

“The term more probably refers to a more nebulous complex of ideas, from the rhythm of modern life to a specific existential feeling, both vital and free as well as aggressive and dangerous, constantly altering between risk and success, mischance and luck.”

The Jazz portfolio is littered with casts of clowns, acrobats and sword-swallowers. The idea of a circus with its clowns was for Matisse a metaphor for an artist’s life, too

Even with this knowledge, the world can’t help connecting Matisse’s playful ode to the circus with the most brilliant musical art form to emerge out of the black Atlantic. It figures though; the connecting dots are everywhere.

For instance, African-American writer and jazz critic Albert Murray was living on the eighth floor of the same building as Matisse at about the time the modernist master was working on many of the cut-outs. There’s a legend among jazz literati about how he walked past the open door of Matisse’s third-floor apartment and saw him surrounded by pieces of coloured paper.

Murray is arguably the single most-important intellectual influence on genius trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who used the image of one of Matisse’s cut-outs from the jazz portfolio Icarus for the cover of his daring 1989 jazz record, The Majesty of the Blues.

It is by this stroke that many South African jazz music lovers connect with the French painter’s later work.

To put on an exhibition of Matisse’s later work in South Africa is a gamble in many ways. First, at the Museum of Modern Art in the US and the Tate Modern in the United Kingdom, similar exhibitions of the master’s work became runaway successes. The Tate saw 560000 art lovers come to see the show, and the MoMa in New York registered an equally high number — in fact, the highest in both institutions’ history.

There’s an unspoken anxiety that, should the show at the Standard Bank Art Gallery not be as successful, it will be an indictment of either the South African arts community or the curator’s and organisers’ savvy.

Locally, the exhibition doesn’t have too high a standard to beat. It only has to be more than the number of people who visited the 2006 show, Picasso and Africa, which attracted an unconfirmed 68 000 people.

Unlike the exhibition of Matisse’s life-long Spanish rival, the curators now have a sexier game to play. The sense of familiarity with the body of work and the jazz tag might connect with the subaltern in ways Picasso couldn’t. It might do what controversies of cultural appropriation levelled against Picasso couldn’t do: tug at the hearts of everyday jazz people and boost numbers.

The co-curators of the show, Patrice Deparpe, the director of the Musée Départemental Matisse du Cateau-Cambrésis, and his South African counterpart, Federico Freschi, the executive dean of the faculty of art, design and architecture at the University of Johannesburg, have worked on an extensive educational programme to deepen the show’s meaning in the broader community.

Henri Matisse — Rhythm and Meaning is on at the Standard Bank Art Gallery from July 13 to September 17. There will be walkabouts hosted by Wilhelm van Rensburg from 1pm to 2pm on July 13, 15, 20, 22 and 29; August 5, 10, 12, 17, 19, 24 and 31; and September 1, 7, 9, 14 and 16