Phoenix is a near-goddess who can lay city blocks to waste with her flames.

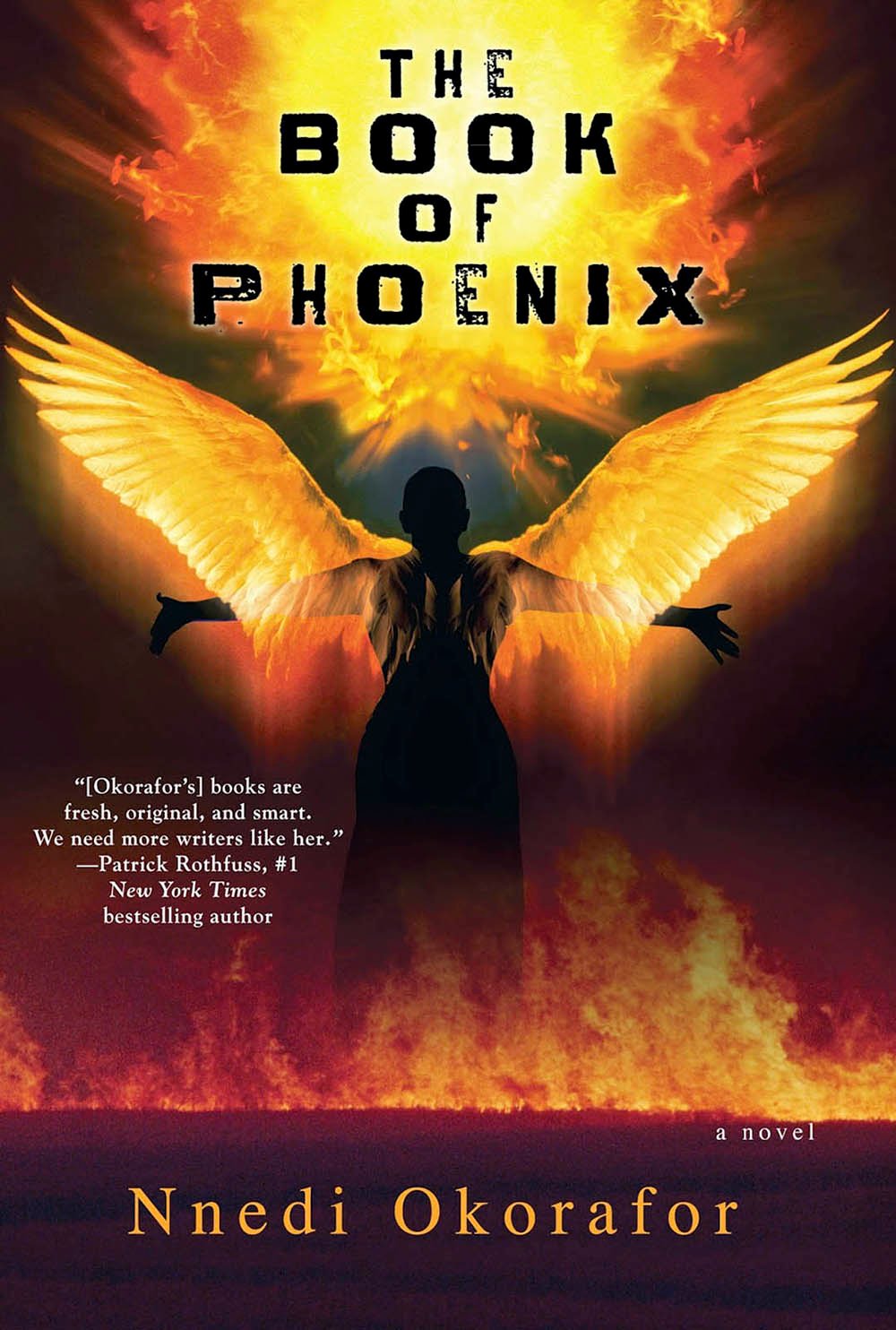

The Book of Phoenix by Nnedi Okorafor (Hodder & Stoughton)

Gwen Ansell

The more levels it works on, the more delicious a book is. Nnedi Okorafor’s The Book of Phoenix – nominated for the Arthur C Clarke Award, to be announced later in August – is a positive millefeuille, with piri-piri between its layers.

Phoenix is an “accelerated woman”, one of a host of genetically enhanced SpeciMen created by a secretive American corporation. She has grown up with her peers, imprisoned in a locked tower, not fully realising the extent or purpose of her superpowers, which include intelligence, light-speed reading skills, rapid healing and eventually – and this is a spoiler, but one implicit in her name – wings and the power to self-combust, creating and then rising from her own ashes. Although regular readers of fantasy know exactly what’s coming when characters develop itchy growths around their shoulder blades.

Already, that might provide sufficient material for a substantial literary riff on superhero fantasies. But there’s more. Phoenix and her peers are almost all of African descent, with their ruthless genetic exploitation presenting a painful metaphor for colonialism, slavery, racism, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the immortal cell line built without permission (or royalties paid) from the cervical scrape of Henrietta Lacks.

After the tower is broken, the SpeciMen break free and travel, moving between Africa and the United States in search of knowledge, healing and finally – as they are hunted down and eliminated by government and corporate goons – vengeance. Despite their powers, these are not one-dimensional cartoon superheroes but people with deep, complex and sometimes just ordinary human emotions.

Phoenix is at once a near-goddess who can lay city blocks to waste with her flames and the girl (she looks 40, but in calendar years she is only two) enjoying doro wat stew or luxuriating in shea butter to ease her flame-cracked skin – even if, in this world, the unguent has bullet-repellant powers. This layer of the tale explores how and why Phoenix and her companions become aware. They embrace the necessity of fighting back, for the sake of self-respect as well as justice.

The destruction Phoenix wreaks ends the old world in which the creation, torture and exploitation of her kind was made possible. Thus the foundations are laid for a new world, the one Okorafor evoked in her debut novel, the award-winning Who Fears Death.

And that reveals the most interesting and challenging layers of them all; the ones that make the book not only a prescient, righteous dystopian tale but also a magnificently crafted work of literature. This is certainly a book concerned with awareness, humanity, racism and the evils of the military-industrial complex. It makes those points powerfully, in ways that move the heart as well as convince the mind – and sometimes evoke laughter, both bitter and warm with recognition. But at the same time it is centrally a book about myths and stories: how they are made and how they impact on the world.

Phoenix’s tale is accessed centuries later by an old man who finds it in a deserted cave full of computers, a cave that also features in Who Fears Death. He and his wife transcribe it, rewrite it and proselytise from it.

“The old African man took the bones, blood and quivering flesh of Phoenix’s book, digested its marrow and defecated a tale of his own. Then he and his oracle of a wife spread this shit far and wide. And their Great Book deformed the lives of many …”

With that revelation on the final page, Okorafor shakes up everything that precedes it. Readers are forced to interrogate their reactions to Phoenix’s tale and, if we’ve read it, even to Who Fears Death. Because we all carry myths from our own Great Books, spiritual or secular, popular or literary. They help shape how we read not only other books but also the world.

Okorafor plays with material from many of them, from Star Wars sci-fi to Kenyan writer Ng?g? wa Thiong’o to African folktale character Anansi to her own short stories and the tenets of various faiths.

Phoenix’s tower prison surrounds a massive tree; we first meet her mentor Seven with outstretched arms, imprisoned against the tree. Because of those faecal Great Books, certain readers will think at that point of Christ on his cross, or Norse god Odin and the immense mythical tree Yggdrasil. But could we not simply see an imprisoned man of colour, yearning to be free – and join in changing the world?