Pick 'n Pay employees on strike demonstrate outside the Gardens' store in Cape Town.

Last month, a Labour Court appeals judgment referred to the salary paid to a cashier by Woolworths as shocking.

“At the time of her dismissal, she was working at the appellant’s store at Maponya Mall in Soweto earning a shocking monthly salary of R2 090.21,” reads the judgment.

Granted, the case dates back to 2010 and the company this week said: “Woolworths pays all of our employees above minimum wages, as per the department of labour’s sectoral determination for retail and wholesale.”

The reality is that, for more than five million South Africans, a job is not a ticket out of poverty because they earn too little.

Despite discussions about a national minimum wage having been on the cards for the past two years, very little has happened.

The National Economic Development and Labour Council established a national minimum wage advisory panel two weeks ago and it hopes to give its first round of feedback in October. The seven-member panel will also have to make a call on how much the minimum wage should be.

Trade union federation Cosatu is asking for it to be about R4 500. Cosatu’s strategies co-ordinator, Neil Coleman, said this would be a safety net to prevent the wages of the most vulnerable from being depressed to such a level that people cannot afford to get to work.

“There are situations where people are being paid just to get to work and they can afford very little else. This kind of situation is very unhealthy for the workers and their families concerned, and it’s unhealthy for the economy because it means that there is very low productivity,” Coleman said.

In June there was an agreement in principle that by the end of this year the implementation phase should have started, according to Coleman.

“Legal drafting and all of these things will start happening soon. We take this seriously and we are very concerned about how long the discussions have taken, so we are hoping that the spirit of that will be taken forward,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Labour Court painted a picture of how the Woolworths cashier was fired for having excess cash in her till at the end of her shift. The court upheld Woolworths’ action but the one line from the judge was telling of many other industries and the call for a national minimum wage.

A 25-year-old woman, also employed in the retail sector, earns R2 800 a month, well below the proposed minimum wage. She asked not to be named because she was scared of losing her job.

“My mother was shocked when she saw my payslip because all this time she thought I was earning good money,” she said. She takes care of her parents and her two-year-old child, and payday can never come soon enough. She says the only reason she can make it through the month without her child starving is because of assistance from her boyfriend.

“There was a time I needed to take a taxi to work every day and that took the bulk of my salary. To cut down on transport fees, I decided to take the bus but that means I have to wake up hours earlier and waste time at the mall before my shift,” she said.

The National Minimum Wage Research Initiative launched by the School of Economic and Business Sciences at the University of Witwatersrand released its report in June. It reveals that there are 5.5-million people working who are technically poor.

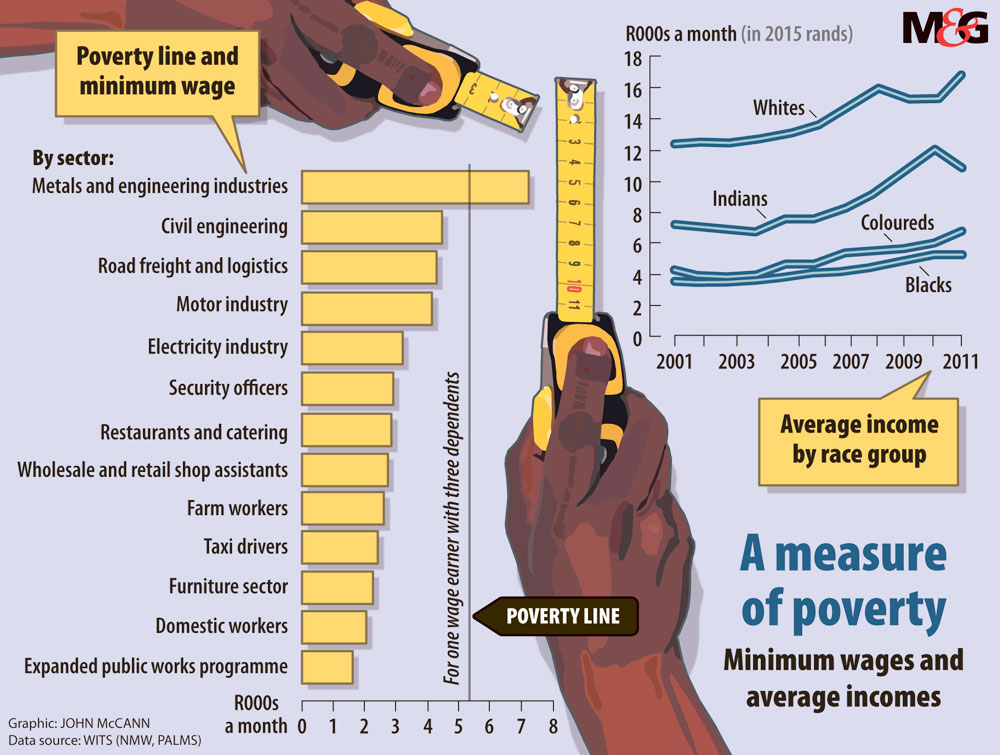

“A high proportion of wage earners in the country live in households that falls below the poverty line. We use a recently calculated poverty line that takes the costs of basic needs of South Africans into account in order to link individual wages to household poverty, and derive a threshold definition for the ‘working poor’ of R4 125 in current 2015 prices,” it notes.

The report, which is mostly based on statistics and international literature, states that a sensible definition of “working poor” considers the fact that wage earners in poor households face higher dependency ratios than wage earners in non-poor households. The research found that each of the wage earners had between two and three dependents.

The picture is grim in lower-income sectors, including those employed through the expanded public works programme, a government initiative to alleviate poverty by providing temporary jobs in the state sector. The department of public works, through a ministerial determination, increased the workers’ salary last year November to R78.86 a day or for a “task performed”. This equates to no more than R2 000 a month.

The report also found that collective bargaining, which covers about 32% of lower-wage workers, has managed to maintain wage levels, although it was unable to deal with working poverty.

Many workers affected by sectoral determination pay continue to earn below the acceptable level, with 75% of agricultural workers earning less than R2 600, while 90% of domestic workers earn less than R3 120.00 a month.

According to the department of labour’s sectoral determination scales, the current minimum wage for domestic workers, calculated at between five- to eight-hour shifts, ranges from R1 412.49 in rural areas to R2 230.70 in urban areas.

The retail sector is supposed to be paying cashiers in the urban areas about R3 660 a month and in rural areas R3 120, according to the sectoral determinations.

Wits’s report states emphatically that a national minimum wage is a modest labour-market intervention aimed at allowing workers simply to meet their most basic needs.

“A national minimum wage could significantly increase wages for South Africa’s lowest earners, benefitting them and their families. In addition, they are predicted to reduce inequality.”

Why Labour Appeal Court found for Woolies

Retailer Woolworths successfully appealed against an earlier finding that firing a cashier for having R628 extra in her till was too harsh a sanction. The Labour Appeal Court last month found in favour of the company.

The case dates back to 2010 when the cashier was hauled up on a charge of misconduct because of the extra cash in her float.

The court had heard that each till operator is allocated a float for the day and, alone, operates the till allocated to him or her. At the end of the shift, the operator then places the day’s takings in a sealed bag, which he or she then drops into a “drop safe”.

A security company collects the bags and transports them to the Standard Bank cash counter. At the bank, the bags are opened and the contents counted under surveillance cameras. The bank thereafter issues a worksheet that indicates whether the money corresponds with what was collected at a particular till. It was at this stage that it was discovered that the employee was in excess by R628.78.

In terms of Woolworths policy, shortages and excesses that are R500 or more have to be investigated, accompanied by a sanction of dismissal.

In this case, there was testimony that the employee in question could not account for the extra cash in the till and appeared to have followed all required procedures.

But she was dismissed and the case went to arbitration. The arbitrator found her dismissal to be substantively unfair on the basis that the sanction was too harsh under the circumstances. The arbitrator also found that the employee’s till takings discrepancy was not the result of any negligence on her part because the employer could not find irregularities in her.

The arbitrator also found there was no evidence that the she had been dishonest or that she intended benefiting from the surplus of the till.

He concluded that a warning would have sufficed to correct the employee’s conduct and ordered that she be reinstated with back pay of more than R14 000. Woolworths lost its initial challenge of this finding at the Labour Court and then lodged an appeal.

Last month, the Labour Appeal Court found the dismissal of the till operator to have been substantively fair.

There was no evidence to suggest that the punishment for the offence was not consistently applied by Woolworths. It could not be disputed that the employee had five previous till discrepancies and was on a final written warning, and the arbitrator had failed to appreciate that the sanction for a transgression of more than R500 was dismissal. – Jessica Bezuidenhout