The crowd at the Union Buildings on August 9 1956. About 20 000 women marched to Pretoria to protest against passes for black women.

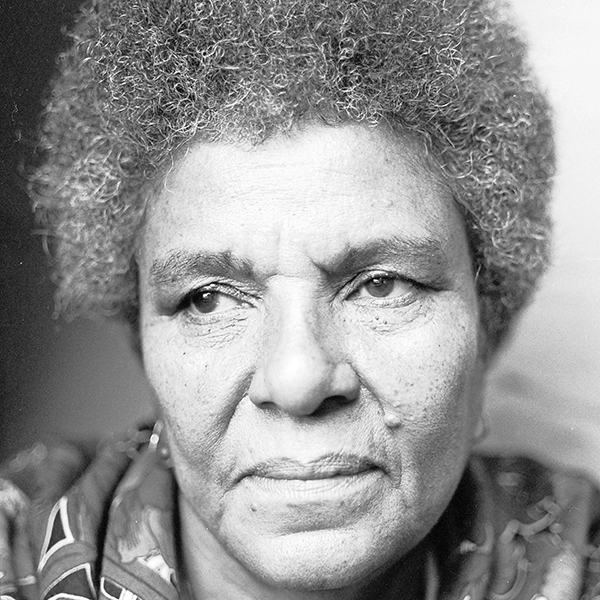

51. Rebecca Koloane

Rebecca Mamokeke Koloane was born near Skilpadfontein in Mpumalanga in 1915. She was employed as a domestic worker before moving to Alexandra in Johannesburg, where she became an active member of the ANC Women’s League.

Affectionately known as “Ma Koloane”, she was active in community projects, particularly teaching women healthy cooking, sewing, and how to buy vegetables in bulk as a way to stretch tight budgets. She played an enthusiastic role in the potato boycott of 1959, when women protested against poor working conditions and slave wages.

In 1955 Ma Koloane moved to Orlando West, where she continued her passionate activism. She took part in the march to the Union Buildings in 1956, and a year later was at the forefront of the initiative by Orlando women to cut cables to houses in their area, to protest against home radios spreading apartheid propaganda. — Linda Doke

52. Rica Hodgson

Rica Hodgson with Ahmed Kathrada (Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Rica Hodgson was born in 1920. She joined the Communist Party in 1946 and in 1953 became a founding member of the Congress of Democrats (COD), which organised white progressives into the mainstream Congress Alliance led by the African National Congress (ANC). She served as the national secretary of the COD until August 1954, when she was served with banning orders.

In 1957, following the arrest of 156 leaders of the struggle, Hodgson became fundraiser and secretary of the Treason Trial Defence Fund and later, in 1961, for the Johannesburg branch of the Defence and Aid Fund, South Africa. In 1959, she was secretary for the musical production King Kong, which promoted black jazz musicians and performances by people of all races.

Hodgson was detained during the 1960 state of emergency. In the build-up to the launch of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the Hillbrow flat belonging to her and her husband Jack was used to produce explosives for the 1961 Sabotage Campaign. She and Jack were placed under house arrest in the same flat in 1962. They left the country illegally in mid-1963 to set up a transit centre outside Lobatsi, in what was then Bechuanaland (Botswana), for MK cadres en-route to training abroad. The couple was declared prohibited immigrants by the British Government and was deported to London in September 1963.

From 1964 to 1981, Hodgson worked full-time for the British Defence and Aid Fund and headed the welfare section of the International Defence and Aid Fund, covertly channelling funds for the defence of apartheid prisoners and the support of their families. During this period, she continued to assist in clandestine ANC and MK work, and her small flat in London was a workshop and meeting place for comrades producing underground material for the struggle at home. Hodgson returned to South Africa in 1991. – Fatima Asmal

53. Ruth Mompati

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Ruth Mompati was born in in 1925 Khanyesa, a village in North West province. A qualified teacher, she worked as a typist at Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo’s law practice in Johannesburg from 1953 to 1961. She joined the ANC in 1954, and was elected to the national executive committee (NEC) of its Women’s League.

Mompati was involved in the 1952 Defiance Campaign and was a founding member of the Federation of South African Women in 1954. She was one of the leaders of the Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria on August 9 1956. She went into exile in 1962, holding office as the secretary and head of the Women’s section of the ANC in Tanzania, where she also underwent military training.

She remained a member of the ANC’s NEC from 1966 to 1973, during which time she was also part of president’s office of the ANC. Mompati also served as the head of the ANC’s Board of Religious Affairs. Between 1981 and 1982, she was the chief representative of the ANC in the UK and became part of the delegation that opened talks with the South African government at Groote Schuur in 1990.

On August 10 1992, a day after the anniversary of the historic Women’s March to Pretoria, she addressed the UN Special Committee against Apartheid in New York on the subject of women. The day was then declared an International Day of Solidarity with Women in South Africa.

In 1994, Mompati was elected a Member of Parliament in the National Assembly. She was appointed ambassador to Switzerland from 1996 to 2000 and upon her return became the mayor of Vryburg (Naledi) in North West province. She died in 2015 at the age of 89. — Fatima Asmal

54. Seapei Kgabale

Seapei Kgabale was born in Winburg, near Bloemfontein, in 1920. She was raised by relatives in Johannesburg and returned to Winburg in her 30s. She was appalled to find the oppression there was far worse than in Johannesburg, and was determined to make people aware that this was not right.

“People had to know that they could have better lives, but that they would have to be prepared to fight for it,” said Kgabale.

Over several months Kgabale and others from the township held meetings to empower themselves.

“The meetings were well attended, and men and woman turned up in abundance,” said Kgabale.

In 1955, shortly after the pass laws were extended to women, Kgabale, together with six women and two men, went from door-to-door, explaining what the new law meant. In a determined show of defiance, they gathered hundreds of passbooks and took them to the local police station, threw them on the ground and set them alight.

“We were determined to get the point across that we were tired of the oppression,” she said.

The following morning Kgabale and 10 others were arrested and charged with treason. The case was thrown out due to lack of evidence.

While eager to change their plight, activists in Bloemfontein were far more conservative than those in Johannesburg, and on August 8 1956, with her one-year-old child in her arms, Kgabale travelled to Johannesburg by train as the only person from Bloemfontein to take part in the planned march on the Union Buildings.

Once in Pretoria, she found herself “surrounded by women who possessed sheer determination to fight for their freedom”.

“The fact that 20 000 women showed up was phenomenal. We spent half the day there, protesting and demonstrating. There was no pushing or shoving. The only commotion was that caused by the police, who sprayed teargas every now and then.” — Linda Doke

55. Sonya Bunting

When Sonya Bunting died in 2001, an obituary in The Guardian described her as “one of a remarkable group of white South Africans who identified unreservedly with the liberation struggle at a time when to support the African National Congress was an almost certain route to prison or exile.”

Bunting was born in Johannesburg in 1922. She joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) in 1942, abandoning her studies in medicine to dedicate herself to political activism. She met her husband Brian Bunting via the CPSA and in 1946 the couple moved to Cape Town, where she worked in the CPSA office, and served as the secretary of the Cape Town Peace Council. The CPSA was banned by the Nationalist party government in 1950, and secretly re-formed three years later as the South African Communist party (SACP), of which Bunting was a founder member. In 1956, she was one of 156 activists arrested and charged with high treason; she spent two weeks in prison before finally being acquitted along with 91 others in October 1958. In 1959 she was banned from attending meetings and ordered to resign from 26 organisations. A year later she was detained for close to four months at Pretoria Central Prison, and in 1962 she and her husband were placed under house arrest. The couple went into exile in London a year later, returning to South Africa in 1991.

In exile Bunting held several positions in the liberation movement, including running the only office of the SACP in the world for 20 years. She organised the World Campaign for the Release of South African Political Prisoners, which mobilised worldwide support for the Rivonia accused and played a significant role in saving Nelson Mandela and his co-accused from the death penalty. Back in Cape Town, Bunting campaigned for the ANC in the 1994 and 1999 elections, worked within her SACP branch and helped to found the Cape Town Friends of Cuba. — Fatima Asmal

56. Sophie Williams – de Bruyn

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Sophie Williams-De Bruyn, aka “Aunty Sophie” was born in Villageboard, a racially mixed area of Port Elizabeth, in 1938. Her father was a community leader and a commissioner of oaths, and many would come to him for aid with their grants and pensions. The young Sophie was touched by their plight: many could not read and write, and her mother opened their home and table to them while her father wrote their letters.

As a young girl, she started working at a textile factory to earn some money. She joined a union, and was popular with her fellow workers due to her eloquent negotiating skills. She was a natural leader and representative to deal with management, and became a shop steward. She left school and continued working at the factory.

Williams-De Bruyn rose to the executive of the Textile Workers Union in Port Elizabeth, which brought her alongside leaders such as Raymond Mhlaba, Vuyisile Mini and Govan Mbeki. An advocate for economic as well as political justice for all South Africans, she was later a founding member of the South African Congress of Trade Unions.

The growing ANC decided an alliance was needed between a likeminded Indian and Coloured Peoples Congress in major urban centres. In 1955, the ANC appointed Williams-De Bruyn as a full-time organiser of the Coloured People’s Congress in Johannesburg.

Williams-De Bruyn was just 18 years old when she joined Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Rahima Moosa in leading 20 000 women in protest against the pass laws. The apartheid legislation classified people into a hierarchy of racial categories, and the leaders of the march represented each of the four main groups, standing united in their opposition to the state forcing black women to carry passes. The ANC Women’s League (ANCWL) took the decision to be fully involved. The success of the march was unprecedented in its mass mobilisation and its seamless execution.

Williams married Henry Benny de Bruyn in 1959; he was part of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto weSizwe. He was forced into exile in Lusaka in 1963, and they were separated for six years before she joined him there. She remained tireless in exile, working as an administrator for the ANC, secretary for the ANCWL, and completing her studies. By 1977, she had her teacher’s diploma, and was deployed to a key position in the ANC Education Council, working in Tanzania and Namibia.

They both returned to South Africa after the ANC was unbanned, and her husband served as South Africa’s ambassador to Jordan until he passed away in 1999.

De Bruyn-Williams continued to work for the betterment of communities after liberation. She served on the ANC national executive committee, and as deputy speaker of the Gauteng legislature from 2005-2009. She then moved to National Parliament, and was also a commissioner for the Commission of Gender Equality.

Speaking to a large crowd at the 60th anniversary commemoration of the Women’s March in 1956 in Pretoria on August 9 this year, Williams-De Bruyn (78) said: “It is for the youth to take up the baton that we have already handed over to them, and to fight the ills and the injustices in our country right now: the increase of the abuse of women and children, and the inequality, poverty and increasing gap between the rich and the poor.” — Romi Reinecke

57. Thoko Mngoma

In 2012, a plaque was unveiled in memory of Thoko Mngoma at a Marlboro clinic named after her. According to the City of Johannesburg’s official website, residents of Alexandra came in their numbers to honour the woman considered by many to be “the mother of the community, an organiser and a revolutionary,” and “speaker after speaker hailed her for selfless service to the community.”

Mngoma was a founding member of the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw), an organisation that advocated for the rights of women. Fedsaw was one of the leaders of the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria against the apartheid pass laws.

Mngoma also helped to form the Alexandra Women’s Organisation (AWO), after the African National Congress and the leaders of Fedsaw were banned in 1960. Under AWO, women would secretly convene at Mngoma’s house, hiding from the apartheid police. Mngoma was a member and supporter of the ANC as well as the South African Communist Party. Her involvement with the latter led her to being placed under house arrest for five years. She played a crucial role in the Defiance Campaign of 1952 and fought against Bantu education.

At the unveiling of the 2012 clinic plaque Buhle Xaba, a representative of Mngoma’s family described her as humble but mighty. “I knew her from my childhood; she was passionate about the community of Alexandra, particularly the youth. Even during the toughest times of apartheid, she would organise us.” — Fatima Asmal

58. Viola Hashe

Born in Gabashane in 1925 or 1926 in the Orange Free State (sources differ), Hashe was a teacher by profession. A pioneer trade unionist in the early 1950s, she served as the assistant secretary of the Chemical Workers Union and the Dairy Workers Union.

Later she became secretary general of the South African Clothing Workers Union, which then became a member of the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu). Hashe became a member of the management committee in 1956, and in 1960 was elected vice-president of the union.

She also joined the ANC in the early 1950s, serving on the Transvaal Provincial Executive of the ANC, and later becoming the first woman regional chairperson of the West Rand region.

In 1956, she was the first woman to be threatened with deportation under Section 29 of the Urban Areas Act. Described as a fiery personality, she fought for the betterment of life for factory workers and black women. She participated in the 1956 Women’s March, and was later jailed.

At the Sactu Annual Conference in 1960, Hashe said: “We will not budge an inch. We will not be divided. The interests of the workers are one.” In 1963, along with Frances Baard and Mary Moodley, she was banned under the Suppression of Communism Act and restricted to Roodepoort, where she lived until her death in 1977. — Tracy Burrows

59. Violet Weinberg

Violet Weinberg worked for the Garment Workers Union, and was a member of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). Her husband Eli was an anti-apartheid activist, photographer and trade unionist.

When the State of Emergency was declared in 1960, both Weinberg and her husband were banned, and Eli was detained for a period of three months. In 1964, Weinberg was called upon to serve on the Central Committee of the SACP. In November 1965 she was arrested and interrogated non-stop for 70 hours concerning the whereabouts of Bram Fischer.

In 1976, at the height of the Soweto uprisings and at the ANC’s bidding, her husband left for Tanzania, where she later later joined him. Significantly, Weinberg was a deputy for Helen Joseph at the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings. Her daughter Sheila was also a prominent political activist. — Fatima Asmal

60. Winifred Siqwana

Winifred Seqwana was born in 1897 and settled in Cape Town, where, in 1930, she became the first African member of the Communist Party of South Africa in Langa. Seqwana became increasingly involved in political activity and was a founder of the Langa Women’s Vigilance Association.

In March 1947 she was arrested for participating in a protest opposing the introduction of beer halls in Langa — in which two people died — but she was later acquitted. Municipal beer halls were not introduced until 1962.

In 1954 Seqwana became the chairperson of the African National Congress Women’s League in Langa. She was also a founding member of the Federation of South African Women, and vice-president of the National Council of African Women. She died in Langa in 1961. — Fatima Asmal

1-10

11-20

21-30

31-40

41-50