Many will know that Charlotte Maxeke is the name of a Heroine-class submarine. And a heroine she was

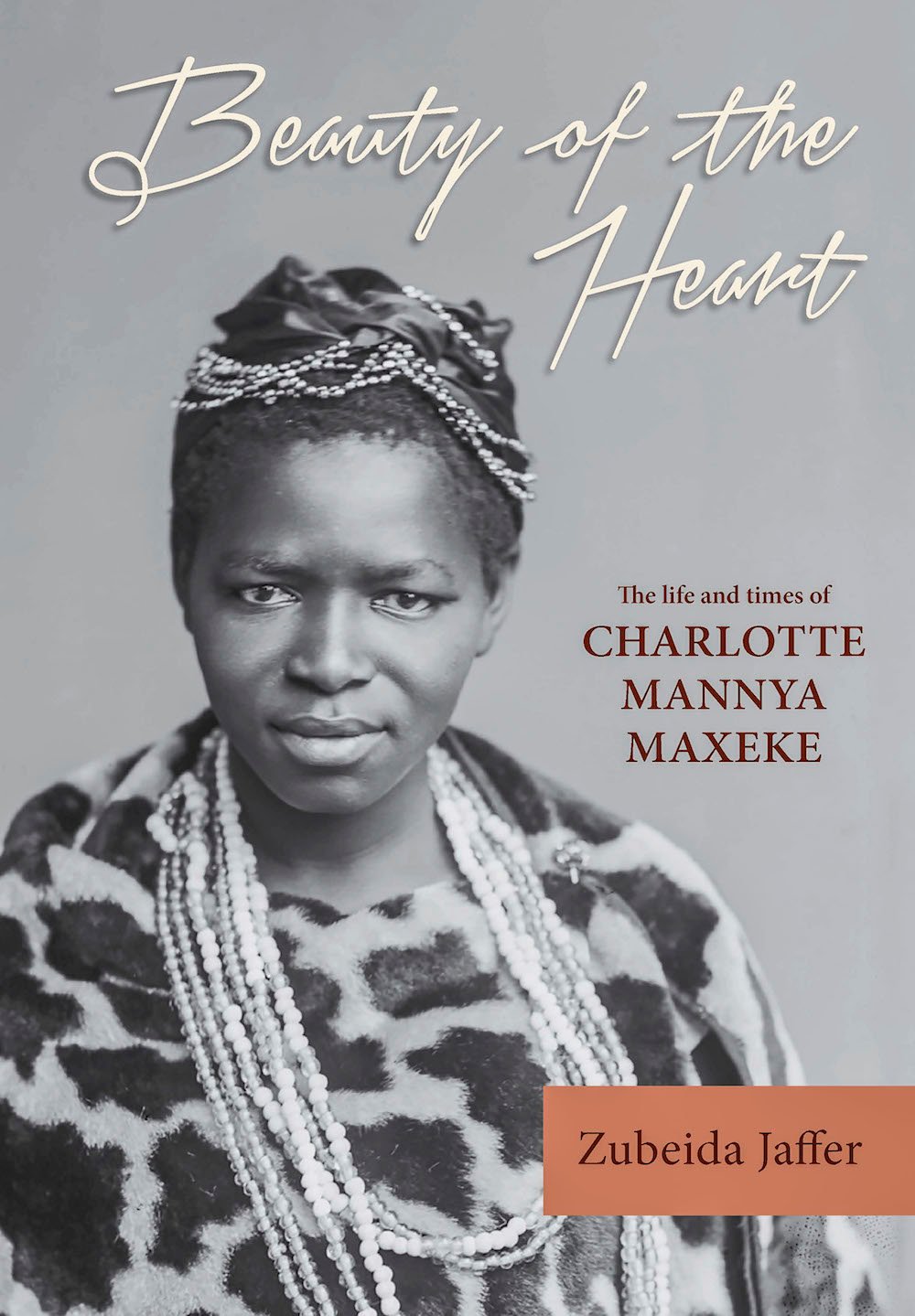

Beauty of the Heart: The Life and Times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke

by Zubeida Jaffer

Sun Media

Beauty of the Heart: The Life and Times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke is the story of a remarkable woman who has long been written out of history and pushed aside in official school and university curricula.

She was South Africa’s first black female graduate, obtaining a BSc degree at Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1901. It was a time when only a handful of white women were accepted for study in the country. No higher education facility would have granted her permission to study in the country of her birth.

Beauty of the Heart pulls together and fleshes out the different strands of her life. It offers the reader historical insight into a woman who deserves to be celebrated by all South Africans.

She travelled abroad, first to Britain and then to the United States, as part of a choir singing indigenous songs and church hymns. Maxeke came home to teach and became drawn into social work activities. She and her contemporary circle of intellectuals were committed to crafting an inclusive society in the last century.

As my research into her life unfolded, a photographic organisation in London unearthed photographs of the choir that had not been made public for 120 years.

In addition, her alma mater, Wilberforce University, has provided a copy of a photograph taken on her graduation day in 1901 and confirmed that Maxeke graduated with a BSc degree but did not do postgraduate studies, as suggested in some texts.

Her early life from 1871 to 1912 touches on a forgotten phase of conquest and resistance often not understood today. It tells the story of how colonialism decisively laid the basis for what was to become full-blown apartheid in 1948. Maxeke did not live to see this. She died in 1939, on the cusp of World War II, which placed Nazism on the world stage. The notion of racial superiority then was to be forever etched into the memories of millions of people. Despite the defeat of Nazism, it had influenced a small sector of the white South African leadership and the idea of racial superiority became the driving force of the notorious system of apartheid.

Maxeke was not to see how all her efforts and those of her circle to develop education would be crushed in the years that followed the war. She, like so many other millions, would continue to be considered of less value in the country of their birth.

Late in 2012, the vice-chancellor of the University of the Free State, Professor Jonathan Jansen, suggested I research and write Maxeke’s story. By then, democratic South Africa had named a submarine and a hospital after her – both odd choices, because she was neither a nurse nor in any way associated with the military.

From about 2000 to 2008, amid great contestation around the arms deal, South Africa had commissioned three submarines that the German builders referred to as “Heroine class” boats. As a result, they were named after three powerful South African women: S101 was named SAS Manthatisi after the female warrior chief of the Batlokwa tribe (Maxeke’s father was a Motlokwa); S102 was named SAS Charlotte Maxeke; and S103 was named after the South African rain queen, SAS Modjaji.

Most members of the public remained ignorant of Maxeke’s significance. If it had not been for the journalists of her time, who recorded her activities, much of the detail of her life would have been forever lost to us.

Pioneer journalist Sol Plaatje is once again the trailblazer. His analysis helps to inform us of her impact as an intellectual, and the role she played with other intellectuals, in the face of the colonial onslaught. The records of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church (AME), published in a number of books, also helped to preserve her thoughts. My book describes her role in bringing this church to South African shores and helping to build it into a strong presence.

Two texts in particular provided considerable direction for this project. First was Margaret McCord’s The Calling of Katie Makanya, published in 1995, based on extensive interviews with Charlotte’s sister Katie. Without this, there would have been no detail of her childhood years. Second was the ground-breaking work of Fort Hare historian Dr Thozama April, whose PhD thesis at the University of the Western Cape was entitled Theorising Women: The Intellectual Contributions of Charlotte Maxeke to the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa.

This thesis had flowed from April’s research into the intellectual inputs of women into the liberation struggle when she was attached to a presidential project commissioned by then-president Thabo Mbeki. It is a compilation of all the documents on Maxeke available in a number of archives – an attempt at compiling a comprehensive archival record. Her work saved the students and me and from having to do this basic research; instead it was our job to study some of this archival material and follow up on further leads.

From the book’s bibliography the reader will get a sense of how widespread our research was. Student researchers helped to dig and find the little jewels of information that could bring Maxeke to life.

The great difficulty was that there were often different versions of her life story. Even her date of birth was contested – 1871, 1872 or 1874? Despite Naledi Pandor, now home affairs minister, taking some interest in the research, no records were found. The year 1871 was the date chosen in the end, because the other dates conflicted with the age of her sister Katie, who was younger than her and born in 1873.

There were also different accounts of her involvement in the women’s protests against the pass laws in the Free State in 1913. There was only one living person who could be interviewed – in a small place called Zebedelia in Limpopo. Aged 106, Hilda Seete spoke of the day when she met Maxeke.

Future research into her life could be fleshed out in many more directions. The vastness of the musical interactions in the Kimberley area, as mining changed its face, is a subject that requires further research. The history of the AME and its relationship to the Ethiopian Movement (a breakaway movement from the Anglican and Methodist churches), efforts to connect with those who had been enslaved in North America and those resisting colonialism on the continent, are areas that deserve being delved into.

Other areas that require further research include the Free State resistance to the pass laws, which Professor Julie Wells is working on, the absence of schooling for the local population at the time and detailed research into the Bantu Women’s League.

Charlotte Mannya Maxeke is one of those historical figures who can inspire generations to come. Researching her life and writing her story was a personal journey of discovery into a time that I knew sketchily and into a life that has affected me deeply.

So long ago, she and her compatriots fought for the right of self-determination for the people at the tip of Africa. They built on the earlier foundations of other intellectuals and bequeathed a legacy that should no longer be absent from school and university curricula.

Zubeida Jaffer is an award-winning journalist and a writer-in-residence at the University of the Free State