Under then-Transnet chief executive Brian Molefe

Sam Sole, Craig McKune, Stefaans Brümmer

Picture: Former Transnet CEO Brian Molefe. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Transnet paid more than R600-million to two companies – one linked to the ANC and the other to the Gupta family – by shovelling ever more consulting work their way without a competitive tender.

The state rail company, insiders say, often paid far too much, and for services that could have been performed internally.

The two companies are Regiments Capital and Trillian, a group that emerged out of Regiments.

Transnet allowed the companies to piggyback on a contract they did not bid for. A R10-million slice of work awarded to Regiments was increased by tens and then hundreds of millions of rands without a further tender, and then Trillian was paid tens of millions more for work earmarked for Regiments.

In amaBhungane’s calculation the total paid to the two companies is well in excess of R600-million. This includes some separate contracts.

These damning conclusions are backed by internal documents and a range of confidential sources both inside and outside Transnet who have told amaBhungane about their anguish – one was in tears – over what they regard as the looting of the parastatal and their fear of reprisals if they spoke out openly.

The allegations greatly amplify the concerns expressed by Futuregrowth when the investment fund announced a moratorium on lending to Transnet, Eskom and other state companies, and add to the body of evidence about the “capture” of parastatals.

The allegations also raise questions about the actions or judgment of senior Transnet staff: its treasurer, Phetolo Ramosebudi, its former chief executive, Brian Molefe, and its former chief financial officer, Anoj Singh.

Molefe and Singh now occupy corresponding positions at Eskom.

Regiments is regarded as being close to the ANC and has previously confirmed that it or its principals made donations to the party.

The Trillian group is controlled by Gupta family associate Salim Essa and is led by Eric Wood, a former Regiments director. Although they are now at loggerheads, Wood remains a 32% shareholder in Regiments.

Eric Woods. (LinkedIn)

Ramosebudi, Molefe and Singh did not respond to questions.

In turn, Regiments, Trillian and Transnet have all denied being party to state capture.

Regiments said: “We state categorically that we do not engage in unlawful practice. We always operate with integrity.”

Transnet said it was “satisfied that the transaction advisory and execution support has delivered significant and measurable benefits to Transnet”. It added: “Any evidence of wrongdoing by Transnet (we are confident that there is none) should be reported to the relevant authorities … Transnet is willing to co-operate with any authority or investigative organisation where necessary.”

Trillian associated itself with Transnet’s comments.

The Regiments balloon: Transnet’s party trick

At the heart of this story is Transnet’s ambitious plan to spend R50-billion-plus on new locomotives to kick-start the growth of its general freight business.

In December 2012 global consulting firm McKinsey led a consortium that won a Transnet tender as transaction advisers for the locomotive acquisition. Their consortium partners included Nedbank and McKinsey’s long-time empowerment associate, Letsema Consulting.

Importantly, financial advisory services were included in the mandate and payment was clearly capped at R35.2-million. Transnet’s formal letter of intent noted: “Any overrun in terms of time will not be for the account of Transnet as the engagement is output based and not time based.”

These restrictions were soon swept aside.

Just months after the contract was awarded, Transnet came up with conflict of interest concerns relating first to Letsema and then to Nedbank. Regiments was proposed as a substitute, although at whose behest remains unclear.

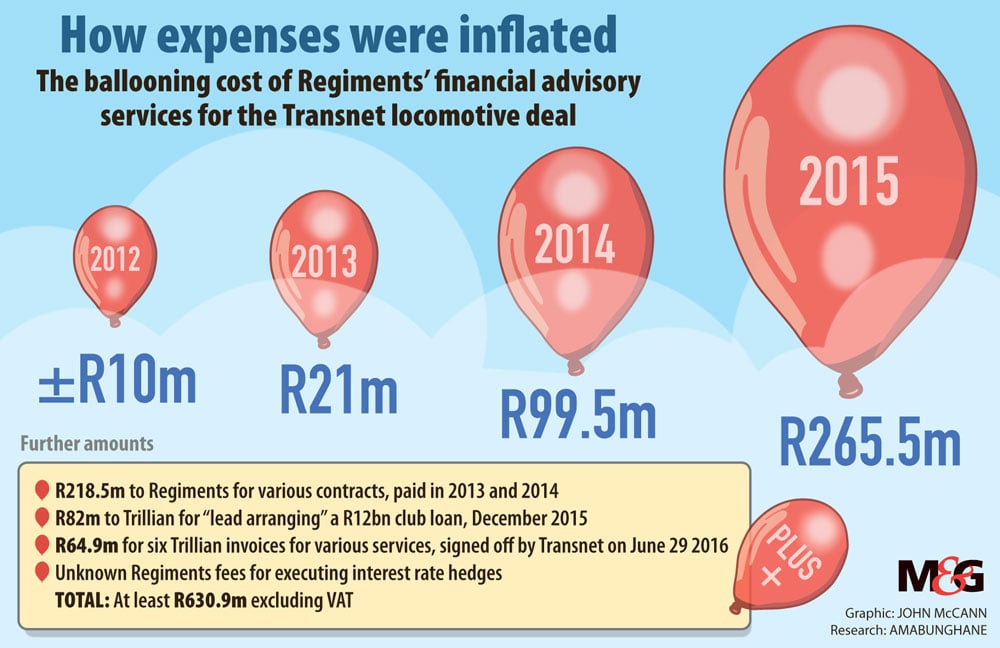

At that point, Regiments was given an estimated R10-million share of the contract. But, as will be seen, there then followed an extraordinary ballooning of the scope and cost of services, driven by Singh and approved by Molefe.

In response to questions, Regiments and Transnet said Regiments was selected and contracted by McKinsey. Transnet said: “Regiments was appointed … on the basis that it was a supplier development partner to McKinsey, which McKinsey had chosen.”

McKinsey declined to comment in detail, citing client confidentiality, but emphasised that it would not be correct to imply that Regiments began its relationship with Transnet through McKinsey. The company noted: “Neither Regiments nor Trillian are currently supplier development partners to McKinsey.”

The balloon gets bigger …

In November 2013 Singh confirmed in writing that the main scope of the engagement was now allocated to Regiments. McKinsey, originally the consortium leader, remained “only responsible for the business case and limited technical optimisation aspects”.

In February 2014 the contract scope for Regiments was amended to reflect the new reality. Although the addendum purported to be between Transnet and McKinsey, Wood simply scratched out McKinsey and signed on behalf of Regiments.

Singh, signing on behalf of Transnet, also increased the contract value by R6-million, bringing the total contract to R41.2-million, of which a R21-million “fixed price” would now go to Regiments.

Regiments said: “We do not have knowledge of the details you describe … Regiments was usually appointed as a subcontractor to McKinsey in terms of the supplier development programme.”

Supplier development of black-owned business is a Transnet requirement in large contracts.

And bigger …

That “fixed price” lasted two months. In April 2014 Singh sent a memo to Molefe in which he now motivated for a post-facto revision in the fee allocation to Regiments, to add an additional R78.4-million.

Singh’s unique rationale was constructed as follows:

Regiments apparently demonstrated to Transnet that it could save money by splitting the locomotive order between four bidders, rather than choosing one or two.

Although this would make each locomotive more expensive, as bidders would have a smaller volume to dilute their overheads, the full complement of 1 064 could be delivered more quickly.

Regiments argued that this would save Transnet in escalation and hedging costs. Hedging refers to the cost of insuring against currency depreciation and interest rate increases until the final payment is made.

Singh also argued that quicker delivery would allow Transnet to grow its freight volumes and earn additional revenue.

The R78.4-million fee was based on Regiments’s own calculation of the billions its advice had supposedly saved Transnet.

Yet those forecast “savings” were explicitly unreliable, with Singh’s memo noting: “The forecasts were based on using historical trends of appropriate indices as calculated by Regiments Capital … The above calculations were prepared to demonstrate the impact of reducing the batch size and will not tie up to the final negotiated position.”

| State capture |

| Wikipedia defines state capture as: “A type of systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state’s decision-making processes to their own advantage through unobvious channels, that may not be illegal.” |

Singh also noted that Regiments had been brought in under a fixed remuneration model accepted by McKinsey, but preferred a “success fee”.

What Regiments preferred, it seemed to get. This amendment to the value of the contract took Regiments’s windfall from R21-million to R99.5-million.

Molefe signed off on what was the equivalent of an employee being given a bonus four times his salary for simply having done what he was paid to do.

Regiments said: “The details you describe … are not within our knowledge. The negative characterisation of the fees we have earned as a ‘windfall’ … is unfounded, inflammatory, and false … We earned our fees in line with the contractual obligations and the professional services we delivered.”

Transnet said: “The initial scope of the transaction advisory work included advising on deal structuring, financing and funding options to minimise risk for Transnet.

“The scope of work was later extended to include execution of the funding strategy. This was driven by an urgent need to respond to the tight delivery period and manage the impact on Transnet’s balance sheet and funding.”

Behind the balloon

In reality, the accelerated delivery schedule has put serious pressure on Transnet’s cash flow, given the actual decline in freight rail tonnage.

In its latest annual report Transnet cautions that a reduction in cash flows from operations could result in it breaching its self-imposed gearing limit of 50%. It also discloses that, as of March 2016, two years after the contract was signed, two of the four bidders had made no deliveries at all.

Treasury falls

Transnet has – or had – one of the largest and most sophisticated corporate treasury departments in the country.

This is the unit that manages the risk and cost of Transnet’s multibillion-rand borrowing portfolio, yet, insiders allege, it was increasingly sidelined in favour of Regiments – and at great cost.

Under Singh, Regiments was now, without any competitive process, also appointed as transaction advisers and to lead negotiation of the terms of a loan from the China Development Bank.

It is alleged that Regiments, with Wood at the helm, acted as Singh’s direct advisers, with neither their role, terms of reference, budget nor their deliverables clearly defined. One source claimed Singh would simply issue ad hoc payment instructions.

The Chinese state-owned bank was proposing to put up the cash to fund the purchase of locomotives from the two Chinese bidders, China North Rail and China South Rail. Insiders claim that both the bank’s initial terms and the fees proposed by Regiments were very expensive – and that outsourcing such a negotiation process was contrary to Transnet policy and practice, given that it had an experienced internal treasury department.

| The numbers |

| R218.5-million – To Regiments for various contracts, paid in 2013 and 2014 |

| R265.5-million – To Regiments for transaction advice on the 1064 locomotive transaction; up to mid-2015 |

| R82-million – To Trillian for “lead arranging” a R12-billion club loan; December 2015 |

| R64.9-million – Six Trillian invoices for various services; signed off by Transnet on 29 June 2016 |

| Unknown Regiments fees for executing interest rate hedges on loans totaling R27.8-billion |

| Total: At least R630.9-million, excluding VAT |

Transnet’s treasury department, it is said, pushed back, but in early 2015 the then group treasurer, Mathane Makgatho, resigned unexpectedly. According to one inside source, she told her staff: “I arrived here with integrity, and I will leave with my integrity intact.” Makgatho declined to comment for this article.

On March 1 last year Transnet appointed Ramosebudi, the previous group treasurer of SAA, to the position. A close relative of his happened to be a trader at Regiments Fund Managers, a Regiments subsidiary.

Regiments said: “The relationship question should be addressed to the individuals … [Our employee] was never involved in any Transnet work … and therefore there was never any conflict of interest.”

Transnet said: “Regarding the use of consultants, Transnet assesses its need for specialised services on an ongoing basis and we award work to external parties based on these assessments, ensuring that there is no conflict of interest with Transnet employees.”

The balloon gets enormous

Ramosebudi wasted little time. On April 28 2015, he compiled a proposal purporting to approve a “contract extension” for Regiments’s support to Transnet on the 1 064-locomotive transaction, raising its fee from the previous R99.5-million by R166-million to total a whopping R265.5-million.

The document credits Regiments with a series of supposedly innovative adjustments to the Chinese loan and estimates the financial benefits to Transnet from the negotiating strategy “pioneered by Regiments” to be in excess of R2.7-billion.

Without citing any contract, Ramosebudi suggests “the financial advice and negotiation support that Regiments provided through this entire process, which took in excess of 12 months, was done at risk with an expectation of compensation only on successful completion of the transaction”.

This transaction was supported by Singh in one of his last acts as chief financial officer before he joined Molefe at Eskom in July last year.

Transnet’s external auditors later queried the R166-million payment, pointing out that Transnet’s treasury was well equipped to handle this transaction.

Regiments said: “All Regiments mandates were underpinned by contracts with clearly defined deliverables … It is best practice that corporates appoint transaction advisers, and does not reflect on the size and competency of the corporate treasury. We cannot comment on the views of the external auditors.”

Transnet said: “All service providers in this transaction were paid for services rendered after we had satisfied ourselves that all obligations were fulfilled in terms of agreed contractual scope.”

Another bid to insert Regiments

Ramosebudi’s April 2015 document also proposes appointing JP Morgan, the huge American bank, to manage the foreign currency hedging on the Chinese loan, which was in dollars.

Ramosebudi purported to recognise Regiments Capital as “the BEE [black economic empowerment] and empowerment partner of JP Morgan to enable Regiments to benefit from a significant transfer of skill from JP Morgan”.

But JP Morgan and Regiments have denied any such relationship.

AmaBhungane was also told that JP Morgan was asked to pay Regiments what appears to have been a form of commission payment in respect of JP Morgan’s work on the Chinese loan. Marc Hussey, head of JP Morgan in South Africa, is said to have refused.

Neither Hussey nor JP Morgan would comment, citing client confidentiality.

Regiments said: “Best practice requires that all fees earned, whatever the mechanism of payment, have to be transparent to the client. Regiments has always complied with best practice.”

Regiments gets more contracts

There followed a series of transactions where Regiments was simply nominated without any tender process for further bouts of financial gymnastics, from which it raked off a percentage. But what Regiments earned was hidden in the overall cost of the transactions.

Three of these related to the cost of changing Transnet’s debt to a fixed interest rate from one that “floated” up and down according to the market rate. This fixed rate was much higher, though it reduced Transnet’s risk.

In one transaction Regiments was engaged to “assist” the Transnet treasury to hedge floating loans amounting to R4.4-billion. Regiments’s fee was undisclosed but was included in the new interest rate. This appears expensive, moving up about 3% compared to the floating rate.

Transnet repeated the process with a R12-billion loan to fund part of the locomotive purchase, appointing Regiments to hedge the interest rate risk on the floating rate. Again, the difference was about 3%. A Transnet insider has claimed this cost R100-million a year more than what a “fair value” price would have been.

Regiments said: “Regiments was always appointed in compliance with procurement policy and the law … The facts are that Regiments has consistently delivered value to the client in all its mandates and has always earned a market-related fee.”

Regiments was then used to execute a further floating-to-fixed-rate swap on R11.3-billion worth of debt, using one of the Transnet pension funds as counterparty (the other party entering into a contract or financial transaction) instead of a bank. It is not clear what the cost of this swap is, but it represents a potential threat to the pension fund, which would not normally assume such a large risk.

Regiments said: “We have never breached the terms of our mandates with respect to risks or otherwise.”

Insiders say many of Regiments’s transactions on behalf of Transnet were done with Nedbank as their only counterparty because other banks were reluctant to trade with them as an “agent” on Transnet’s behalf.

At one point, even Nedbank decided that the reputation risk was too large and refused to continue paying Regiments as an agent of Transnet, insisting that Transnet pay Regiments directly.

Nedbank said: “Confidentiality in our dealings with clients is central to our business integrity at Nedbank. We are therefore not at liberty to respond with any detail to your inquiry.”

Regiments said: “Regiments has conducted hedging transactions for its clients with a number of banks, on a fully transparent basis with respect to its clients in relation to fees.

“We have most often been paid the fees via the bank counterparty since it simplifies the accounting treatment for the client. There are banks that are not happy to pay the fee, but I would suggest that this is for competitive reasons as opposed to reputational reasons.”

The balloon pops and out bursts Trillian

The Transnet feast was too good to last – and there is a technical term for what happened next: kleptoparasitism. That’s when one predator steals another’s prey. Wood, the 32% shareholder in Regiments, was by all accounts the Regiments rainmaker at Transnet, but in late 2015 he jumped ship from Regiments – and took Transnet with him.

In March this year Wood formally joined the newly established Trillian Capital Partners, in which his family trust holds a 25% share. The 60% shareholder is a company called Trillian Holdings, where close Gupta family associate Essa is the sole director.

One source close to Regiments claimed that Wood first got to know the Gupta family around the time of the infamous landing of their wedding party at Waterkloof airforce base in 2013.

It appears that in late 2015 Wood’s Gupta connection began to cause friction and was an underlying reason for his parting from Regiments, which saw Regiments’s advisory business, including staff, assets, liabilities and certain contracts, being transferred with him.

The separation was not a happy one, but on March 15 this year, Regiments informed Transnet that Regiments would assign part of its business to Wood in terms of a separation agreement, that Wood was injecting the business into Trillian, and that Trillian could step into the shoes of Regiments to execute work on the “outstanding contract”.

In April the Transnet board approved the cession from Regiments to Trillian.

Now Regiments says the separation agreement with Wood has not been finalised and accuses Wood of undermining their business, something Wood vehemently disputes.

He insists the parting was “initiated with the full sanction of the Regiments board”.

The extent of Trillian’s windfall by inheriting Regiments contracts is unclear, but amaBhungane reported in August that Trillian had already been paid R82-million by the end of February and that Transnet chief financial officer Garry Pita signed off further Trillian invoices totalling R74-million at the end of June.

It seems the Trillian hyena has displaced the Regiments jackal – and it’s their turn to eat.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Sign up for our newsletter to get more.