Ernest Dikgang Moseneke being congratulated by his friends and family after being admitted as an attorney

In an edited excerpt from his autobiography, Dikgang Moseneke describes how he and his and his fellow prisoners were sent on their way to Robben Island after their conviction in 1963 for sabotage.

“All line up, face the wall and take off your clothes,” a voice commanded.

On July 2 [the day of sentencing] we were well into winter, and the afternoon was cold and overcast. We all stood naked. I had never seen an adult naked before. The instructions continued. “Every new prisoner washes and shaves. The showers are on your right and the razors are in a bowl nearby.”

In no time our shivering bodies were dripping and our heads were cleanly shaven. Were there towels in prison, I wondered. No. We stood naked and wet.

To our left were piles of items of prison clothing. You had no choice of size. Seemingly a choice was redundant. Their clothing was styled to fit all. The items were massive in size, certainly way too big for a young lad like me, even a growing one. The pants came without belts but there were pieces of long cloth sewn on to the waistline. Mine went twice around my tiny waist. The shirts were collarless and crinkled. I supposed it was prudent to save inmates the bother of keeping a collar sanitised. Similarly, it would have been tricky to iron the shirts. You could add an army brown jersey and open-toed sandals. These appeared to be optional. We chose the sandals and the jerseys. It was very cold. The prison did not issue underwear nor socks.

The next order was that we surrender all personal belongings. I had none save for the little pile of clothes I’d left on the floor when I had had to submit to the freezing shower. Those who had them gave in their identity documents, cash, watches and jewellery, pens, books, toiletries and other personal effects. Gone were the external markers of material well-being. From then on the amenities or perhaps the lack of them was even. We all shared the lowest denominators.

We were issued with a prison kit: an aluminium plate with dents everywhere, a cobbled coffee mug, a spoon, a felt mat and three grey-black blankets. But it was what we were not given that struck home. Besides no underwear, the kit had no pyjamas. Did we sleep in the same clothes? We were not issued with a toiletries pack. How were we supposed to wash our faces and brush our teeth?

We looked around at each other in our over-sized prison garb and clean-shaven heads. No one had the courage to say a word.

We were in an ominous transition. My will had been supplanted by their will. I was a prisoner and would be for the next 10 years. Was this, I wondered, a fair example of an average day in prison? Would the prison break up our group and spread us across cells of hardened criminals? That, more than anything else, struck the fear of God into me. What was more, that and all other vital decisions were not mine but theirs.

When the kit process was done, one of the African warders shouted: “Two, two umthetho wasejele!” We marched in pairs, each carrying his prison issue, along a long corridor with many gates to pass through. Each gate was manned by a warder. Habitually, the warder who led us would say “Dankie hek” to get the gate opened.

After many winding corridors and stairs we were all put into an empty communal cell, which had apparently been cleared to hold us. Prison doors are never closed gently and quietly. As they banged closed, we were all frozen by the deep discovery that we were indeed convicted captives. And yet we were silently relieved that we had not been strewn across ominous prison cells. We were still together. We might have been stripped bare and cold and then dressed in strange apparel, but at the end of the day, we had each other. When you walk a difficult road, you do well to have a companion at sunset.

One of my naughty erstwhile classmates – it could have been Absalom Nkwe or Mike [Matadingoana Michael Mohohlo] –came apart laughing and pointing at me. “Hey, s’boshwa, hey, prisoner, your attire is crazy. Look at your wrap-around pants and skinny head.”

The jokes rippled across the cell as we laughed out loud at ourselves and at each other in our new, awkward look. The laughter was merciful.

We randomly picked sleeping bays the size of a felt mat. You had to place the mat on the floor with one blanket over the mat and two over your body. Before long all of us had taken refuge under the blankets.

The following morning, I rose feeling stronger and certainly less afraid than the previous day. “Mike,” I said, “I am no longer a 10-year prisoner. My sentence is one day less. I am left with nine years, 364 days.”

After our first prison breakfast we were ordered out to the reception for the admission paperwork. We spent the morning in a queue. They took down personal details. You had to rehearse your family tree. We submitted to fingerprinting and photographs.

The process matched slave logbooks. You had to drop your pants and lift your shirt and open your mouth wide because they wanted to record every scar, deformity, unusual feature or teeth pattern. The session of the day ended with a prolonged medical examination. It came across more as a bodily data-gathering than an effort to detect or exclude illness.

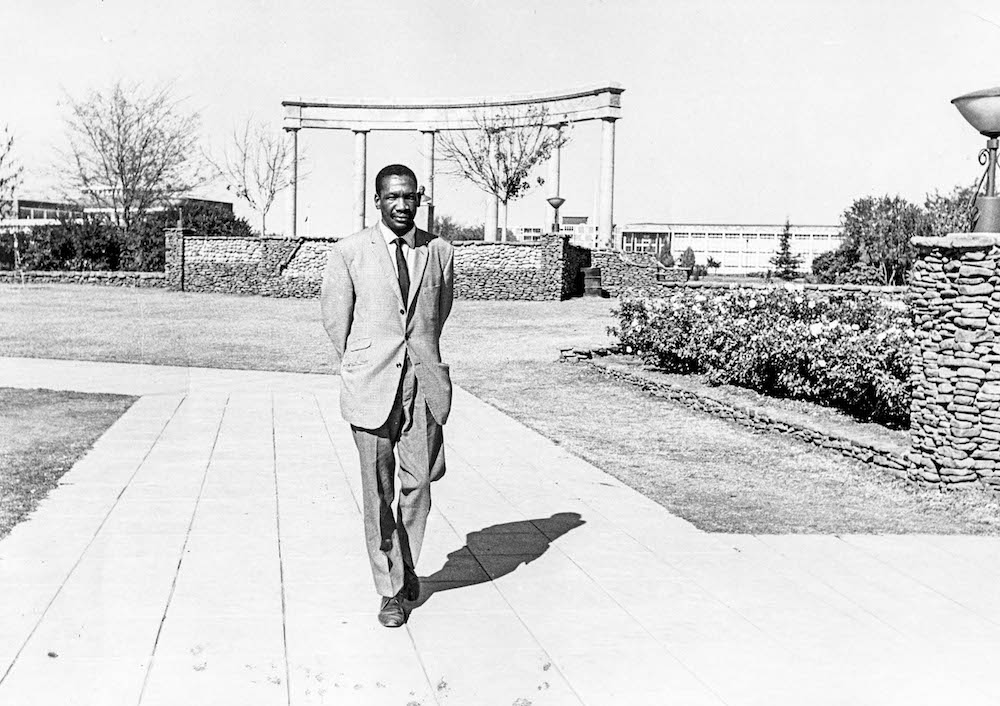

Robert Sobukwe in the 1950s. (Avusa/Gallo)

Then I did not know as fact what they were recording. Now I do, thanks to the National Archive, which recently gave me access to my prison records. The detail of my physical description is truly chilling. It displays a remarkable disregard for personal privacy in favour of a single-minded objective to know your enemy and captive down to the finest detail.

We had no idea how long we would be kept at Pretoria Central Prison. It turned out to be only for a few days. During the second week of July, at the crack of dawn we were woken up, handcuffed hand to hand and chained leg to leg. Like Siamese twins, we were forcibly attached to each other.

Chained in pairs, we had to negotiate the little steel steps up into the back of the yellow closed police truck. It was a very chilly morning. They never formally told us that they were trucking us to Robben Island. We worked this out through an unguarded conversation in Afrikaans, when our captors talked about stopping over in Ficksburg and reaching Cape Town the following afternoon late.

The trip was horrible. The back of the van was porous and the canopy was made of steel mesh. The icy breeze blew right through the steel caging and it froze us to the bone. The warders had tossed a few blankets at us, and placed a drum of drinking water and a bucket for toilet use in the back. With the movement of the vehicle the water drum tipped and water slopped out, soaking most of the blankets. The security convoy never stopped for nearly 10 hours as it charged towards Ficksburg in the Orange Free State.

We might have been cold outside but inside we were warm. We were set to serve our long prison terms together on Robben Island. Hopefully, it would be a prison standing on open and generous grounds. That had to be better than a claustrophobic inland maximum-security prison. The maximum-security class of facilities permitted a prisoner a 30-minute walkabout in the courtyard in the morning and another in the afternoon. That was the sum total of natural light we could hope to see in a day in New Lock. There was a more felicitous reason to cheer up, too. We had come to know that there were other political prisoners on Robben Island. At that time, in July 1963, the most significant of those detainees was Robert Sobukwe himself.

The reason for Sobukwe’s detention on Robben Island boggled the mind. After the 1960 anti-pass campaign, he served three years’ imprisonment with hard labour. While we were in solitary confinement during April 1963, Parliament passed the so-called Sobukwe extension clause. This was an extraordinary piece of legislation. It was not a law of general application. It targeted the liberty of one person. The law decreed that Sobukwe must be kept in continued detention, even though his prison term had ended and he had not been tried and convicted of an offence. The Sobukwe extension clause was renewable every year by Parliament. The PAC [Pan Africanist Congress] and the ANC had both been declared unlawful organisations and the government was on a path of political repression.

To her credit, politician Helen Suzman stood up in Parliament and opposed the measure most strenuously. She was the only opposition member in Parliament. She bemoaned the fact that a law had imposed an egregious and unlimited breach of a citizen’s personal liberty without a fair trial and a finite punishment.

We spent the night at Ficksburg prison. The prison accommodation was comfortable and certainly better than the truck ride. We were also untied from the shackles. The dinner was good – the best we had had, in fact, since our conviction.

Next day, again at the crack of dawn, we were placed under restraint once more and loaded back on to the trucks. The convoy set off to Cape Town, into the Cape winter rain and wet wind, which did not let up as we drove into the docks at about 5pm.

Dikgang Moseneke recently retired as deputy chief justice. My Own Liberator: A Memoir is published by Picador Africa