According to Mthethwa

In the rolling hills of KwaZulu-Natal and in its urban crevices, believers on either side of the Nazareth Baptist Church will say one thing in unison: the case is over but the case is not over.

Such is the interregnum that has pitted uncle against nephew and, among its rank and file, has turned parents against offspring.

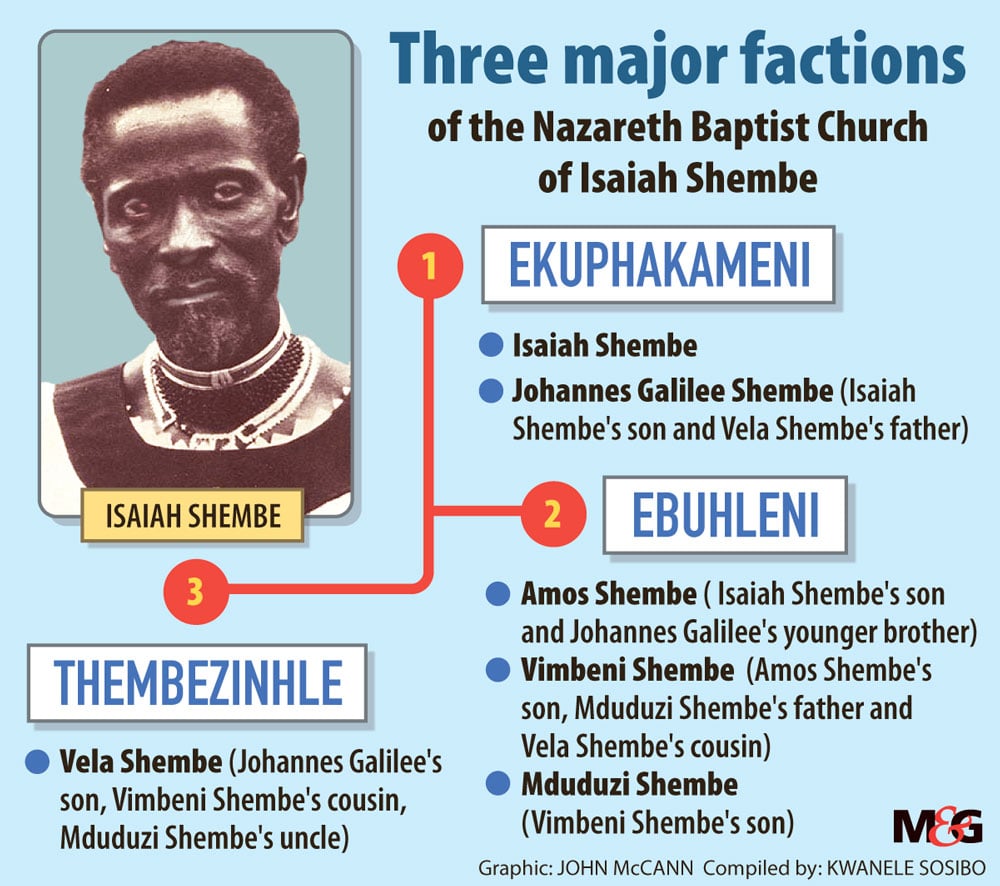

At the heart of the stalemate in the church’s largest faction, based at Ebuhleni in Inanda, is a succession battle between Vela Shembe and his nephew, Mduduzi Shembe.

On April 3 2011, the date of Ebuhleni leader Vimbeni Shembe’s funeral, Mqoqi Ngcobo, the chief of the Emaqadini Traditional Council, announced Mduduzi (Vimbeni’s son) as the winner of the succession race and not Vela (Vimbeni’s cousin).

Vimbeni’s lawyer Zwelabantu Buthelezi announced the contents of his late client’s nomination deed. The name he read out was that of Vela.

But the bluster of the chief had won the day. Buthelezi, who was under police guard, hurriedly left.

The effect of the day was huge, for besides the five million-strong congregation and the legitimacy they represent, church assets worth millions of rands were at stake.

Vela was educated and groomed by Vimbeni while Mduduzi, with only a primary school education, is seen by some as a pawn of an influential cabal of priests, who enjoy Ngcobo’s support.

In the court action that followed to dispute the legitimacy of Mduduzi, his uncle Vela applied for an interdict to freeze a trust worth hundreds of millions of rands in the name of the church and, later, another interdict for Mduduzi not to be customarily installed as the new head.

The court battle went on for five years.

In October KwaZulu-Natal Judge President Achmat Jappie concluded that the deed of nomination signed by Vimbeni was valid, making Vela the legitimate successor. This will be appealed before a full Bench of the high court.

A village settlement of thousands, Ebuhleni doubles as the

church headquarters and the residence of Mduduzi. It is a picturesque, flat-topped hill near the Inanda Dam, stretching out between deep gorges.

It stands in contrast to Esibusisweni, the home base of Vela Shembe’s exiled Thembezinhle faction. Esibusisweni is situated along a busy stretch of tar road connecting Ebuhleni to Ekuphakameni, where Isaiah Shembe established his church in 1911.

Vela’s Esibusisweni, which is one of the properties Isaiah bought as he set up camp in Ekuphakameni, is essentially a family compound, with several outbuildings and a small family grave site overlooking a congregation yard.

Just as thousands ascend Ebuhleni every Saturday to commemorate the Sabbath, a few score gather at Esibusisweni for the same reason.

Despite the high court decision declaring Vela the legitimate leader of Ebuhleni, Mduduzi remains the de facto head of the church, having been secretly sworn in during a ceremony in March 2013 as the court battle progressed.

Mduduzi enjoys the devotion of millions who say the court case is inconsequential, despite draining the church purse to the tune of millions in the past five years.

In a video taken moments after the judgment was announced, Mduduzi, dressed in his high-collared robe and fedora, proclaimed to a huge uniformed crowd covering the expanse of Durban’s Albert Park: “Those that claim to have won seem unhappy for they know their victory is hollow.”

Amid deafening shouts of “Amen,” he continued: “In Ebuhleni, nobody holds the keys to Gethsemane besides myself. And finally, nobody has the strength to carry ubhoko [staff] that I carry to the mountain [in the annual pilgrimage].”

It seemed Mduduzi was about to proclaim himself lord over all the world before stopping himself and dropping the microphone in melodramatic fashion.

Inside the courtroom, by contrast, Vela thanked the courts for vindicating his late cousin.

Menzi Msomi*, who backs the Mduduzi faction, says: “The case and its outcome are insignificant to us.

“It has never been the courts who decide who assumes power. Instead of breaking our faith, this decision makes us more resolute.

“The reason we keep the faith is because of the works this church has done. We receive blessings. My son asked for a job and he received one overseas. I don’t have a fancy job but look at my house.”

The bearded, lanky Msomi lives in peri-urban Inanda, a few kilometres from Ebuhleni. His house has marble tiles and a 150cm flat-screen television.

Although the church is not strictly patrilineal, any deviation from this has always led to major splits.

Church legend has it that its founder, Isaiah Shembe, had ordained that two particular sons successively take over the reins of the church on his death, beginning with Johannes Shembe.

When Isaiah’s second-anointed son, Amos Shembe, tried to assume power following his elder brother Johannes’s death, Londa, one of Johannes’s numerous sons (and Vela’s brother), would have none of it, forcing his uncle Amos to leave Ekuphakameni in the late 1970s. Amos then set up at Esibusisweni.

When Amos died, his son Vimbeni became leader. On Vimbeni’s death the succession battle resumed through Vela and Mduduzi.

On a humid Friday afternoon before the beginning of the 24-hour-long Sabbath observance, the greying, bespectacled and barefooted Chancey Sibisi, for a time Vimbeni’s right-hand man, sits at the satellite temple of Esibusisweni.

“When the congregation is reunited with the rightful leader [Vela],” says Sibisi, “all those properties [in Ebuhleni] and everything material will return to Shembe [Vela]. That’s where Shembe will stay, pray and walk. Whatever belongs to the Nazarenes, the Nazarenes shall return to.”

Sibisi is speaking of a divinely ordained return to Ebuhleni, which is so physically near (10km) to yet so symbolically far from the Esibusisweni temple.

In the meantime, the Thembezinhle faction remains in a sort of religious purgatory, hardened hearts and the threat of violence elongating the distance between Esibusisweni and Ebuhleni.

It is this inclination for violence and the show of numbers that Ebuhleni regularly relies on that will ensure that Vela never ascends the Ebuhleni throne.

“If you read the judgment, they [Mduduzi] have no case,” says Sbu Shembe, a church member related to Vela Shembe and aligned to the Thembezinhle (Esibusisweni)faction.

“They thought they had the numbers to exhaust us financially so that the case dies. Remember that the general membership has no clue as to what is going on. They only know that the king [the leader of the church] is worshipped.

“I’ve heard that people have become rich off this case and bought houses in Ballito [a wealthy enclave on the KwaZulu-Natal coast].

“The longer the case drags on, the longer the congregation forks out for lawyers. It’s just a moneymaking scheme. They [Mduduzi] may even push this to the Constitutional Court.”

In Jappie’s judgment, he ordered that Ebuhleni pay the costs of the Thembezinhle faction’s court fees.

An Ebuhleni member, Nomzamo Dube*, while leaving the temple after Mass, quips that framing all this is a bid to “capture” the church and make it pay taxes. “Often the government tried to threaten the late leader Vimbeni into paying taxes but he refused. You need to ask yourself: Who is funding Thembezinhle’s case, as tiny as they are?”

The comments are probably without proof, but they heighten the sense of obstinacy and paranoia that dominates both sides of this marathon court battle.

In the midst of the deadlock, brothers and sisters that once fed off the same nipple refuse to attend each other’s funerals, locking their supposedly divine connections into the ghettos of turf war.

* Names have been changed because members of the Ebuhleni faction may not speak to the media