The government's sugar tax will affect consumers of soft drinks.

On the way to work on Monday, I turned around to find my two-year-old sucking happily on a discarded sugar sachet, with another clutched tightly in his sticky little hand. A battle of epic proportions ensued as I tried to confiscate the packets, while he frantically shovelled as much of it down his throat as he could.

Another fight over sugar has been intensifying as the government contemplates a proposed 20% tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB).

The lobbies from both sides will face off in parliament next week at public hearings on the tax, held by the standing committee on finance and the portfolio committee on health.

In the run-up to the hearings, a new report by Priceless SA, a division of the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of public health, was released this week, which explored fiscal policies on population health. The report was the work of a panel co-chaired by former Constitutional Court justice Kate O’Regan and Leila Patel, the director of the Centre for Social Development in Africa, at the University of Johannesburg.

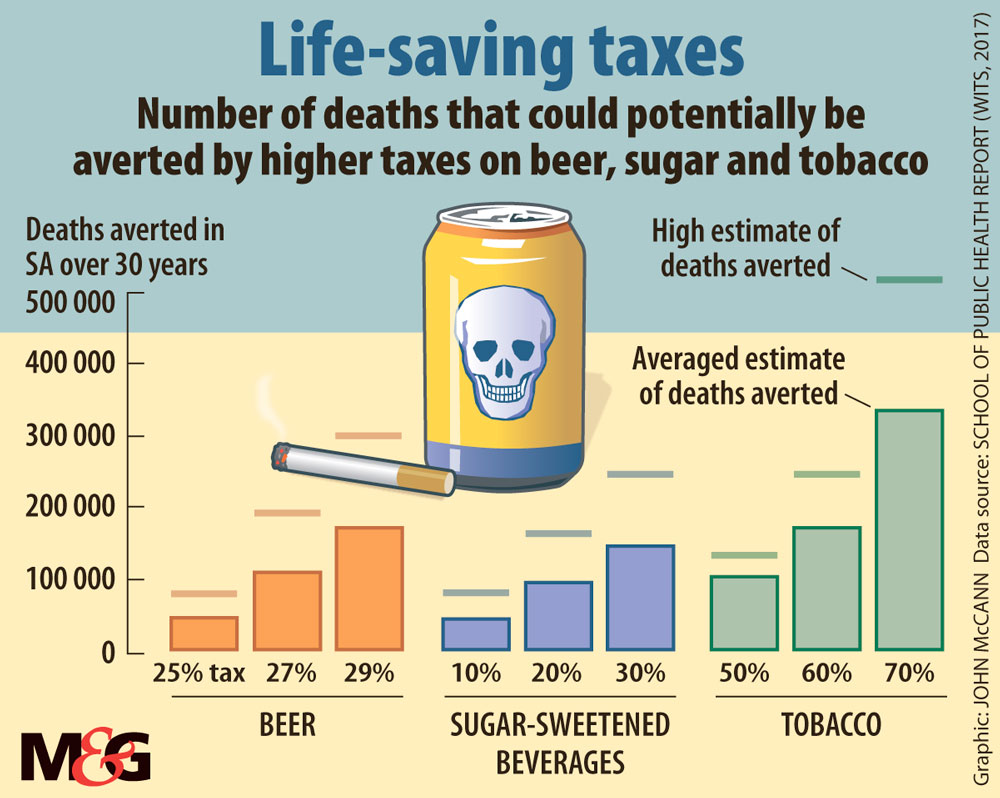

It examined a range of measures, from tax incentives to cash subsidies, and their potential for improving health without requiring additional budgetary allocations. As part of its findings, it suggested that increasing taxes on alcohol and tobacco and introducing one on sugary drinks will have major health benefits, reduce the burden on the healthcare system and help to raise revenues.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has come out in support of countries aiming to impose taxes on sugary drinks.

The WHO’s Dr Taskeen Khan, who spoke at the release of the Priceless SA report, said a 20% tax could lead to a similar reduction in consumption.

The savings in healthcare are another reason to do this, according to the WHO. It estimates that, over 10 years, a tax on sugary drinks of $0.01 an ounce (28.3g) in the United States would result in $17-billion in healthcare cost savings.

The Priceless SA report does not put a number on the revenue that the tax could generate in South Africa. But Priceless SA health economist Nicholas Stacey said, based on initial estimates, a 20% tax could raise between R5-billion and R7-billion.

South Africa is not the only country considering a tax on sugary drinks; the United Kingdom is among other nations planning to do so.

In 2014, Mexico implemented a 10% tax on sugary drinks and initial research on its effects appear to be positive. A report by the Mexican National Institute of Public Health suggested consumption declined by 6% in 2014, 8% in 2015 and 11.1% in the first half of 2016. It also found that after the tax was introduced there were no reductions in the number of employees in the sugary beverage or food manufacturing industries, or in the downstream businesses that sold these products.

The local debate over the tax comes at a time when there is a growing discussion about the role sugar plays in our lives. Science journalist Gary Taubes is arguably leading this charge with the release of his book, The Case against Sugar.

He makes a compelling, unashamedly anti-sugar argument for considering sugar as a “chronic toxin”, which should be seen as a major, if not the major, cause of rising obesity levels and diseases like diabetes.

He decries past dietary science, which he believes has given sugar a free pass. It has done so in part by maintaining the line that eating too much of everything and not expending that energy is why we get fat and sick; and for the persistent assumption that one nutrient cannot be blamed for so many chronic ailments.

There is another explanation for these problems, argues Taubes, and that is sugar. According to him, it has historically had an enormously powerful lobby behind it, which has succeeded in, if not outrightly corrupting nutrition science, certainly muddling it to the extent that clear conclusions become hard to reach.

He concedes that the science is not definitive but believes it is compelling enough to argue that sugar should be seen as a toxic substance and suggests that even a call for sugar in moderation may be naive.

But he does end with the point that the question, “how much is too much?” (as with alcohol, caffeine and tobacco), is ultimately a personal choice that adults make knowing the risks. And, like smokers who take on the battle to quit, unless we try to live without sugar, we will never know.

Taubes’s work has coincided with exposés published in the likes of the New York Times revealing how the sugar industry funded and influenced research into nutrition over decades, minimising the link between sugar and heart health and focusing the blame on the role of saturated fat.

It remains to be seen how a tax on sugary drinks in South Africa would work, or whether it will have any unintended consequences.

The social justice organisation Section27, which supports the tax, does note in its submission on the treasury’s policy paper on the tax that the regressive nature of the tax does bring into sharp focus the need for greater access to affordable healthy food. “Without such a change, the SSB tax will limit the calories available to many South Africans,” it said.

The soft drinks industry has warned of economic effects, including losses of between 62 000 and 72 000 jobs, according to a study done for the industry body BevSA.

These figures have been widely criticised, most notably by Neva Makgetla, a senior economist at the economic research body Trade and Industrial Policy Studies (TIPS).

She argues the industry’s claim that job losses, particularly in the value chain, will be catastrophic are premised on exaggerated estimates of total employment dependent on sugary drink production and sales, and on the assumption that producers cannot shift to the production of healthier untaxed drinks.

In its submission, Section27 also argued that jobs could be created in the fruit-growing or juice industry as a result of a switch to fruit juice, while the sugar cane or corn syrup currently being used in sugary drinks could be used to produce ethanol.

Nevertheless, concern about the wider economic effects persist. Research by the economics consultancy, Econonex, using Nielsen data, suggested that demand for sugary drinks is inelastic — in other words, South Africans might not cut their consumption of sugary drinks if prices rise.

A more “muted” reduction in sugary drinks will result in a lower health effect, according to the Econex authors Nicola Theron and Paula Armstrong. But even a small change in consumption habits, could have negative effects, they said.

According to three different scenarios testing for price elasticity, Econex claims that each of these reduce gross domestic product growth between 0.09% and 0.1% in the first year, depending on how much consumers change their behaviour.

Proponents of the tax argue that the potential savings in healthcare justify the tax, particularly given that the poor have the most to lose when they get sick. As Priceless SA notes in its report, “the poor who become ill will bear a higher cost for their consumption than the wealthy”.

Healthcare professionals have also pointed out that critics of the tax have not considered the long-term increase in incomes for people that results from better health, or the fact that less disposable income goes to medical costs.

In at least one assessment of the sugar tax, done by the advisory firm KPMG, it notes that a 20% tax could save the healthcare system about R10-billion in the coming 20 years through reduced costs of treating type 2 diabetes alone.

But the trade-offs may not be easy. Sugar is ubiquitous, making its appearance in most processed foods. For many people, choosing healthier food can be expensive and, given questions of availability and access, it can also be seemingly impractical.

As with my son, I see many more battles over sugar to come.