'I could have died': Buhle Bhengu was duped into having an illegal abortion.

The young woman started undressing while the man prepared the medication, breaking one tablet in half. She took off her jeans and her panties and lowered herself on to the mattress on the floor.

The man put on a pair of white surgical gloves, then got down on his knees at the foot of the makeshift bed. He slowly pushed the tablets into her vagina.

The 23-year-old woman was lying in a flat in downtown Johannesburg. She stared motionlessly at the ceiling.

“It wasn’t painful, just uncomfortable,” she recalls. “But I had no choice.”

An overpowering smell of incense filled the room. The woman remembers: “It looked like a place where they worked with muti.”

The man explained the procedure. He was going to give her medication. “Some of the pills I would have to drink at home, the others he would insert inside my vagina.”

The woman pauses.

“I got his number from an advert in the newspaper. It said: ‘Safe, pain-free, same-day abortion’.”

Clandestine Affair

Earlier that day Buhle Bhengu, who chose to not to use her real name, arranged to meet the man from the advert in Lilian Ngoyi Street.

She followed him up the dark staircase of a derelict building to the room where he would perform her abortion.

The medicine he gave her would induce the abortion, he explained. The second set of pills he told her to drink with water at home would “cleanse her womb”.

In South Africa a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol can only be used for

performing an abortion for up to nine weeks in pregnancy, according to health department guidelines.

But because mifepristone is about R500 a tablet, many of the clandestine and the official providers use misoprostol only, says Eddie Mhlanga, an obstetrics and gynaecology specialist.

“Misoprostol is given vaginally and then later orally. The vaginal tablets soften the cervix and the oral dose of misoprostol cause the uterus to contract more and expel the fetus.”

After 14 weeks it is necessary to give misoprostol, followed by a drip with oxytocin to stimulate the uterus to expel the fetus. Thereafter the woman has to have manual vacuum aspiration in theatre.

Bhengu was 20 weeks pregnant.

In South Africa, a legal abortion can only be performed by a midwife, a registered nurse trained for the procedure, a general practitioner or a gynaecologist.

Bhengu doesn’t know whether the man had medical qualifications. She knew him only as Peter.

How to spot an illegal abortion

[multimedia source=”http://bhekisisa.org/multimedia/2017-02-08-how-to-know-if-your-abortion-is-illegal”]

There was blood everywhere

When Bhengu got home she drank the pills as instructed. A few hours later she started experiencing excruciating pain in her abdomen.

“I went to the toilet and I saw blood on my underwear. There was just blood everywhere.”

Bhengu was terrified.

“I didn’t know what to do. I had my first baby by Caesarean section; I was not prepared for the labour pains.”

While she was trying to figure out what to do, Bhengu received a phone call from Peter. He wanted to know how she was feeling.

“He said: ‘Just push, you’re going to be okay.’ ”

She remembers: “It didn’t take long for it [the fetus] to come out. I think there was a human-like form. Then there was more blood but it was transparent, I didn’t really get a good look at it. I wrapped it in a towel and put it in a black plastic bag.”

Bhengu stored the bag behind a shack in her backyard. It had to stay there for five days until the garbage would be collected.

Although abortions in South Africa are legal up to 20 weeks of pregnancy, second trimester abortions (between 13-20 weeks) have to be performed surgically by a registered general practitioner or gynaecologist. The law states that surgical abortions must be done in facilities that have an operating theatre, nurses and doctors as well as the appropriate medication in case of an emergency.

Because she had Caesarean deliveries previously, there was a greater risk of her womb being torn and that is why the termination needed to be performed in a hospital, says Mhlanga.

“If only I had gone to the clinic,” says Bhengu, “I would not have seen what I saw that night. But I was scared the nurses would judge me.”

Buhle Bhengu is still haunted by an unsafe abortion she had many years ago. (Hannah Brunlöf)

Buhle Bhengu is still haunted by an unsafe abortion she had many years ago. (Hannah Brunlöf)

Lack of services

A 2016 study in the Journal of Southern African Studies estimates that one in five pregnancies around the world ends in abortion. But “unsafe abortion is notoriously difficult to quantify” and, according to the study, “there is a dearth of statistics on illegal abortion in South Africa”.

Yogan Pillay, the deputy director general in charge of maternal and women’s health in the national health department, says no data is collected on illegal abortions because this would be “logistically impossible”.

But Jane Harries, director of the women’s health research unit at the University of Cape Town, argues: “A lot of people don’t want to access [use] the public sector [facilities], although the actual procedures are safe, because of the stigma or the way they’re treated by staff or out of fear that they might be recognised by someone from the community.

“Women use many different ways to terminate a pregnancy or attempt to terminate a pregnancy outside of the formal health system.”

Government not doing enough

Amnesty International, the global human rights organisation, recently released a briefing report on unsafe abortion in South Africa. The research found that only 260 of the 3 880 public health facilities in the country carried out abortions.

This shortage, the 2016 Journal of Southern African Studies article states, “undermines women’s access to safe abortion service, and fosters the reliance on clandestine abortion providers”.

Harries says the situation is exacerbated by “the plethora of online advertisements” that make it increasingly difficult to differentiate between people who carry out legal abortions and illegitimate ones.

This was the dilemma Bhengu would face seven years after her first abortion, when she wanted to terminate another pregnancy.

“I found out I was pregnant in June last year. By then I was already four months along,” she says.

Her fiancé had lost his job several months earlier, so Bhengu, who works for a nongovernment organisation, was the sole provider for her family of four. “My partner said he would support any decision I took because, financially, I was a single parent.”

Bhengu knew she wouldn’t be able to support another child, so once again she decided to have an abortion. Only this time she was going to make sure she went to a real doctor.

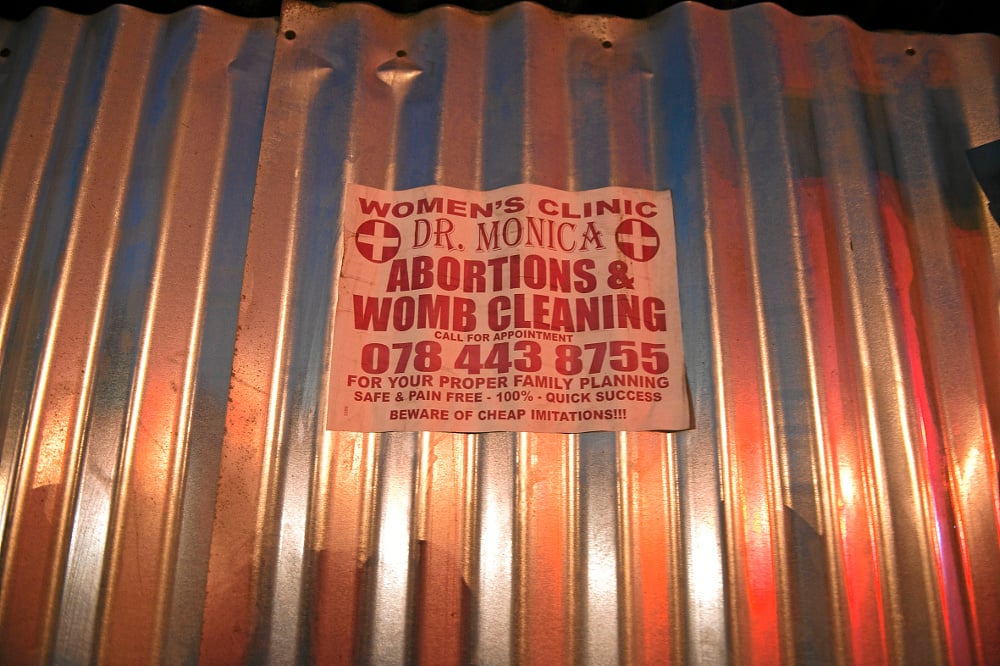

Posters advertising illegal abortions are a common sight. (David Harrison)

Posters advertising illegal abortions are a common sight. (David Harrison)

“I searched on the internet because I figured that the doctors on the internet would be real – unlike the ones who advertise in newspapers,” she says. “The first call I made was to Marie Stopes, but they told me the abortion would cost R3 800. I earn only R4 000 a month.”

Marie Stopes is a nonprofit organisation that provides donor-subsidised sexual and reproductive health services at lower rates than most private facilities. Prices range from R1 050 to R5 000, according to the organisation’s Whitney Chinogwenya. The further along a pregnancy is, the higher the cost.

“Our prices differ between first and second trimester as the second trimester procedures require a trained doctor to provide the service. In some cases, clients also need an anaesthetist,” says Chinogwenya.

Bhengu, who was already 16 weeks pregnant, discovered that her local clinic had a month-long waiting list.

“I kept on looking and found ‘Dr Pinky’; she charged me R1 200.”

Better than the last time

In August, Bhengu went to “Dr Pinky’s” consultation rooms in the inner city.

“I trusted her because she gave me counselling. She asked why I wanted to do this; if I had told anyone about my choice. She also told me the advantages and disadvantages of having an abortion.”

Bhengu remembers thinking:

”This place is much better than where I went before.”

The “doctor” told her about the drugs she was going to receive and what they were for.

“After that she took six of the pills and broke them in half. The ‘doctor’ said these would induce the abortion. She told me to insert six in my vagina and to put six under my tongue when I got home.”

At this point, Bhengu became suspicious and asked whether the procedure shouldn’t be done in the doctor’s office.

“Dr Pinky” told Bhengu: “We don’t do everything here. You’ll just come [after taking the pills] and I will clean you after this [abortion] has happened.”

Many women do not know what the abortion entails. (Gallo)

Many women do not know what the abortion entails. (Gallo)

Although misoprostol is used in the later stages of the second trimester, this drug alone is not enough to complete the termination, says Mhlanga. It softens and opens the cervix so that other drugs can cause the uterus to contract and expel the fetus without causing injury to the cervix.

It is for this reason that second trimester abortions are carried out in hospital. After the expulsion of the fetus, the remaining contents are removed with forceps and a manual vacuum aspirator.

Bhengu remembers that “nothing happened when I took the medication. I started getting labour pains but there was no blood.”

The next day, Bhengu went back to “Dr Pinky”, who gave her six more pills. “I took them because I had already paid for the service,” she recalls. “But the pain got worse. My stomach was racing. It felt like the baby was fighting.”

That night Bhengu was rushed to a private doctor’s practice. The doctor had her admitted to hospital, where he performed a surgical abortion and explained to her that she was meant to have had that procedure done in the first place.

“He said I could have died.”