Sassa

NEWS ANALYSIS

Late in 2016, nearly two months before the national budget was presented in Parliament, the South African Social Security Agency (Sassa) learnt it might need R1-billion extra a year to ensure that social grants would continue to be paid.

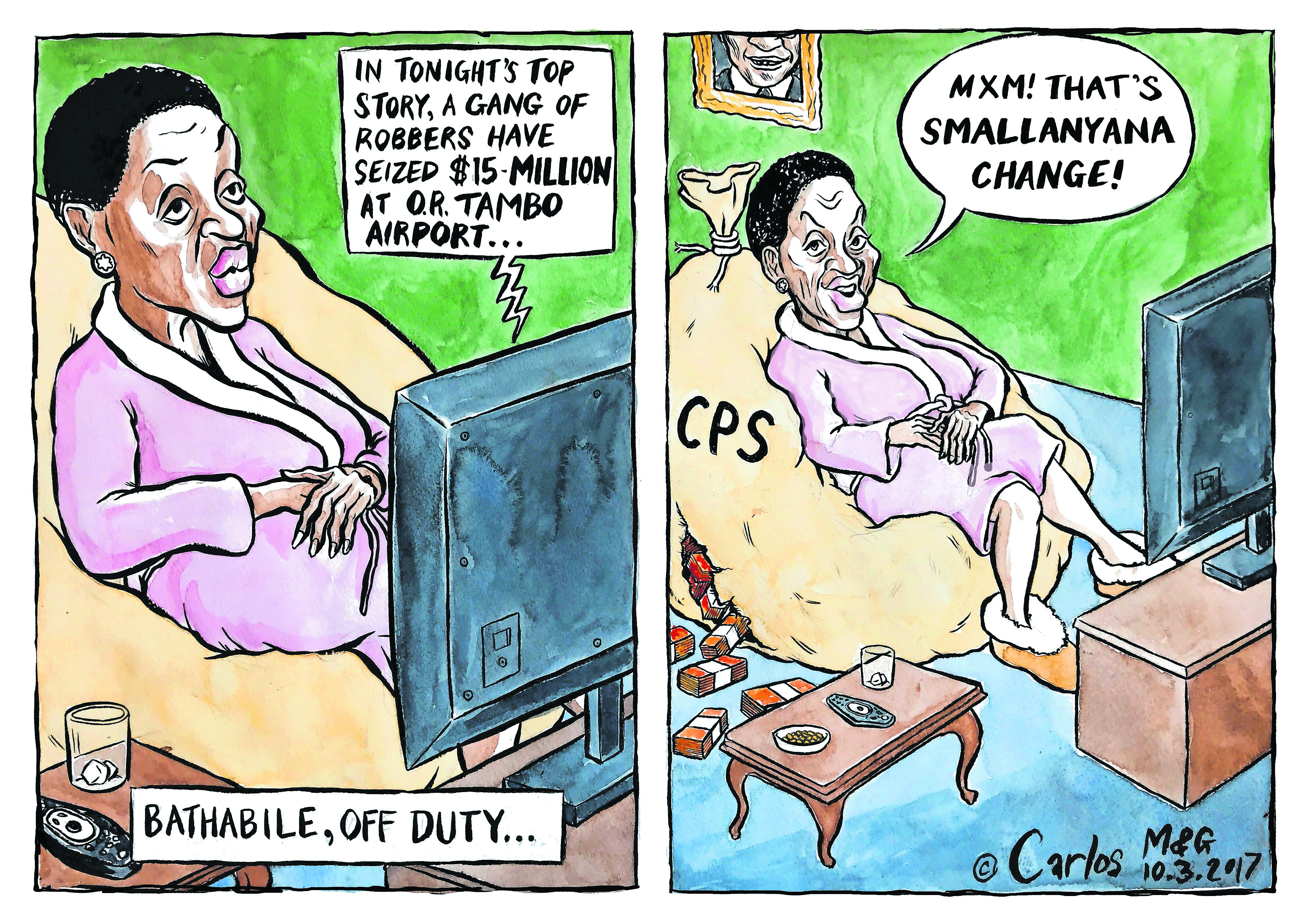

Sassa, the department of social development and its minister, Bathabile Dlamini, did not seek to secure that extra money. Instead they lied about the existence of that number and then lied about its origin, telling Parliament that it was a Sassa estimate rather than a demand it had little choice but to pay.

This much is apparent from the documents submitted last week to the Constitutional Court.

Directions issued on behalf of the Concourt on Wednesday demanded specific answers to many of the questions that Sassa and Dlamini have so far managed to obsfucate or outright refused to answer: Is there a new contract with CPS? What are its terms? Produce it please. Name the person responsible for deciding that Sassa could not itself take over the payment of social grants. On what exact date did Sassa realise it would not be able to follow the timeframes that it had previously told the court it would follow?

These questions all related to the fact that the court’s decision to stop supervising Sassa’s award of the grants tender was based on a report to the court by Sassa in November 2015 that it would be able to take over payment of social grants itself.

Over the past weeks, Dlamini and her subordinates repeatedly assured the nation there was no possibility of a disruption in grant payments.

They also maintained in front of two committees of Parliament, which will have to divert money away from other key spending areas to foot the bill, that there was no reason for concern around costs.

But submissions to the Concourt suggest the cost to the fiscus would balloon if Sassa stays with Cash Paymaster Services (CPS). The agency now says it has no other option.

The increased amount required remains unclear. Sassa has negotiated with CPS but, according to Dlamini at her press conference last week, is not yet ready to sign off on a deal. On March 5, Independent Media reported only R230-million extra was required.

If that number had been agreed on, Dlamini still sought to withhold it from Parliament.

“I am not an expert on everything,” she told the standing committee on public accounts (Scopa) when asked about the costs, during a meeting she attempted to leave to avoid questions entirely. Dlamini had previously told Scopa that it should not discuss pricing details because it could jeopardise negotiations.

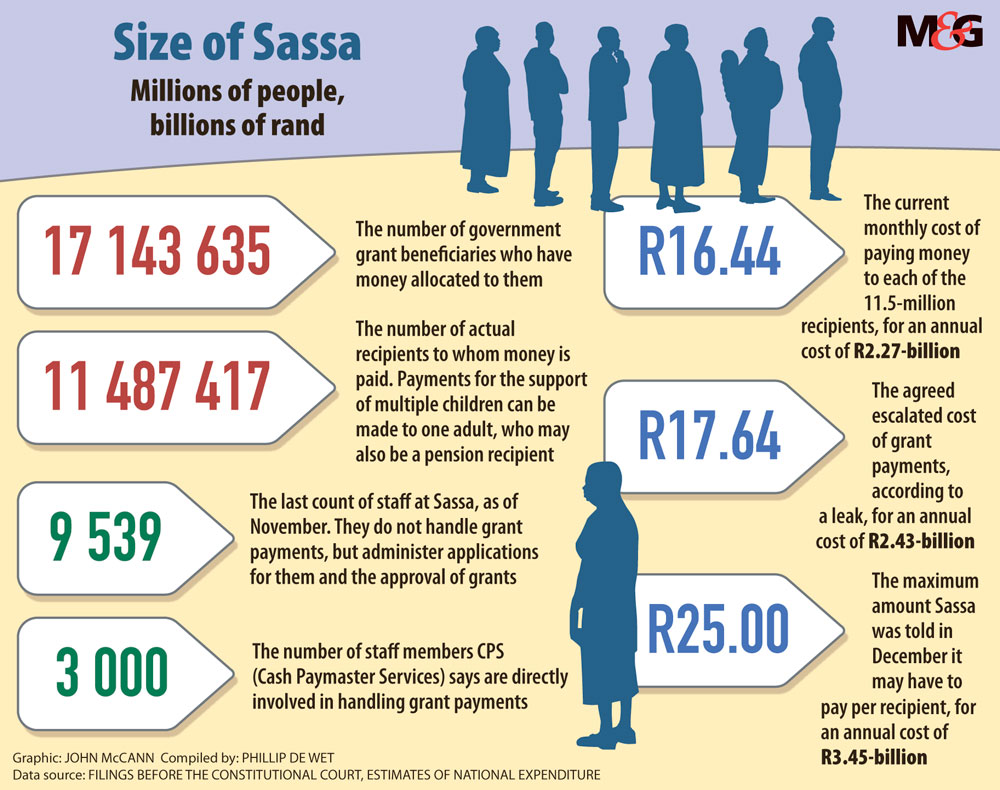

But, as papers before the Concourt show, there was never any secrecy about price. Sassa wrote to the chief procurement officer of the treasury on February 7 to say it estimated that it would have to pay CPS between R22 and R25 a month per grant recipient, or a total of between R3.1-billion and R3.5-billion over the year.

Compared with the rate of R16.44 it has been paying for five years, that represents an increase of about 50% — and a possible total extra payment of some R1-billion.

Sassa initially said it could not possibly have written such a letter because it had not even started negotiations with CPS. Confronted with the lie after Sassa put the same letter before the Concourt, Sassa said the numbers were an estimate.

Sassa’s manager for the social grants project, Zodwa Mvulane, went further. She had personally come up with the R22-to-R25 figures by using an inflation calculation, she said.

“It is not the amount that the current service provider might be charging us,” she said, before official negotiations with CPS had started.

But that is exactly what it was.

On December 28, documents put before the court by CPS show the company wrote to Mvulane by name. The letter estimated its “short-term price offer” to increase from R16.44 to R25 if Sassa wanted the power to terminate a contract with 90 days’ notice. For a two-year contract the price would be R22, it said.

Whether it is R200-million or more than R1-billion, lobby group Freedom Under Law (FUL) said this would be “pure profit”, because the company’s costs had already been paid over the past five years.

FUL entered the court fray last week, joining the case brought by civil society group the Black Sash.

FUL said there would be no legal way to pay more than R16.44. The court should rule that CPS may also not be paid any other fees or amount “meant to supplement or otherwise undercut” that restriction.

Top advocates (including those consulted by Sassa) concur that there is no way that a new contract under which CPS is to distribute grants could be legal, because it flouts procurement rules. The Concourt previously ruled that CPS may not profit from an unlawful contract, but also said it should not “result in any loss” to CPS either.

The R16.44 number was set in 2012 and has not been adjusted since, so this could mean a loss for CPS.

In the same December 2016 letter to Mvulane, the company’s Serge Belamant says clearly that the fee would have to increase to between R22 and R25. The letter also plans for CPS phasing out of the process.