Tough love: Teenagers need to be informed and need to have access to contraceptives.

Schools may soon be banned from forcing girls who have given birth to remain at home for months — or even more than a year — before returning to class.

A new draft national policy on preventing and managing pregnancy among learners, drawn up by the department of basic education, states that “the school will accept and be flexible in dealing with these absences”.

It adds: “The school, its principal and educators will be nonjudgmental, supportive and sympathetic to each case.”

Until now, many schools have enforced discriminatory policies against pregnant pupils in the absence of national regulations.

Some have insisted on using the controversial 2007 measures for preventing and dealing with pregnancy among schoolgirls, drawn up by Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga’s predecessor, Naledi Pandor, even though they were revoked in 2011.

These guidelines suggested that pregnant girls take a leave of absence from school of up to two years so that they could, among other things, take care of the baby.

The Mail & Guardian this week found that the teenage pregnancy policy of Hoërskool Langenhoven in Pretoria stipulated that a girl who gave birth in, for example, June of her matric year would not be allowed to write her final exams at the end of that year.

According to its policy, if a learner “delivers” in December, “she will only be allowed to return to school in the second January following the birth”.

It was also established that several schools in Mpumalanga still advise pregnant teens to stay at home once they are seven months pregnant and to return only after their newborn is at least a month old.

The department conceded in its latest draft policy that the mandatory leave of absence in the 2007 guidelines was unconstitutional and that, “as a result of misguided enforcement of the measures by schools, several pregnant learners were forced to leave school under the pretext of provisions in the measures”.

It stated that one of the goals of the new policy was to reduce the incidence of schoolgirl pregnancy by providing quality comprehensive sex education and access to youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services.

“The primary goal of the policy is to promote girls’ constitutional rights to education by ensuring they are not excluded from the school as a result of pregnancy and birth, and to provide the supportive environment for the continuation of learning,” the policy says.

“No educator, school staff member or fellow learner may discriminate against, humiliate or abuse a pregnant learner in whatever way.”

The procedures for handling teen pregnancy are clearly spelled out in the 20-page draft policy. They include suggestions that:

- The school should appoint a teacher from the senior management team to assist the learner when

she discloses her pregnancy;

- The appointed educator, with representatives from the departments of health and social development, as well as the police, if required, will provide a support system;

- This support system will show the pregnant learner how she can access counselling services and will inform her of her constitutional right to continue with her education during and after her pregnancy;

- The school will refer learners to the South African Social Security Agency if they wish to apply for a child support grant; and

- Should a learner be visibly pregnant but have not told her school that she is expecting, the responsible educator may approach her to advise her of her right to access healthcare services, among other rights.

- Should the policy be approved, teachers will have to provide curriculum-linked education packages for learners who are absent for a spell after giving birth.

The draft policy also proposes that if a learner is aged between 12 and 16 and divulges that she became pregnant through a consensual relationship with another adolescent, if the age difference between the two is not more than two years, “then no crime has been committed”.

The draft policy also addresses the issue of teachers impregnating schoolgirls: if a schoolgirl reveals that she became pregnant after having sexual intercourse with an educator, “a serious breach of professional trust and violation of the learner’s right has occurred”.

“This must be immediately reported to the school principal or designated social worker.”

Describing the draft policy as both “revolutionary and radical”, Pedro Makwattie, head of life skills and HIV and Aids education in the Northern Cape education department, said it addressed the gaps in the 2007 pregnancy guidelines.

“The guidelines [the mandatory two-year leave of absence clause] infringed on the rights of the learner. The draft policy is more progressive. The ball is now in the court of parents. If they feel the child is ready to continue with school, it’s up to them.”

In a chapter included in the recently released Education Rights Handbook, Lisa Draga, Chandre Stuurman and Demichelle Petherbridge from the Equal Education Law Centre said that pregnant learners often faced “reluctant teachers” who were not willing to support them by giving them access to books, notes and homework while they were at home.

“Pregnant learners are increasingly also being requested to provide the school with money, in case they need medical assistance while at school. Others have been forced to have a guardian accompany them to school at all times.”

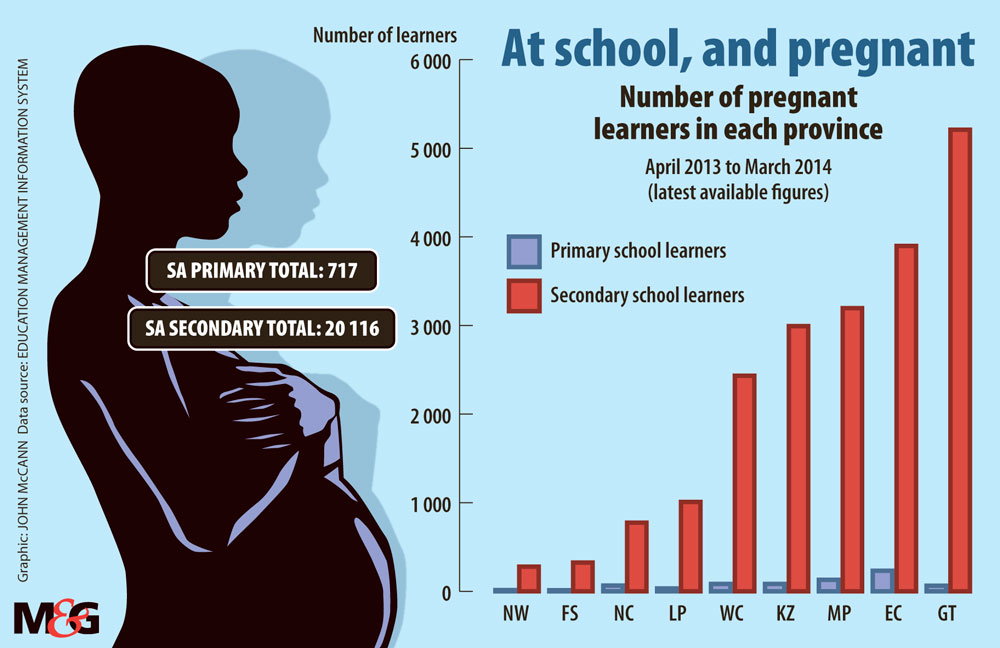

They said that schoolgirl pregnancy was being dealt with differently by the various provinces in the absence of a national policy in this regard.

“School governing bodies have been left to determine their own learner pregnancy policies without any guidance as to what is lawful. In many instances, these policies have been highly discriminatory.”

Christelle Erasmus, head of the school-based support team at Hoërskool Langenhoven, said that if a pregnant matric learner was capable of writing her final exams she was allowed to write them.

“We prefer that they don’t write because they can go into labour but we don’t shoo them away.”

She said girls who became pregnant were advised to take a temporary transfer to the nearby Hospital School Pretoria.

A principal of a school in Mpumalanga, who did not wish to be named, blamed the high incidence of teenage pregnancy on girls having boyfriends both inside and outside school. He confirmed that pregnant girls were advised to stay at home once they were seven months pregnant.

A grade 12 learner at this school, who returned to class this year after dropping out in 2015, said she bitterly regretted getting pregnant. “I came back because I want to have a better future so that I can provide for my 11-month-old baby,” she said.