Queuing to collect government grants in Alexandra.

This is the story of Aletta Bezuidenhout.

The 35-year-old mother of two, who received two child support grants, applied to the microfinance firm, Moneyline, for a loan in early 2016.

To do that, she says she was told to go through a process that involved the scanning of her cellphone SIM card and her fingerprints, and the issuance of an EasyPay Everywhere card. It came with the instruction that she was no longer to use her South African Social Security Agency (Sassa) branded card to transact.

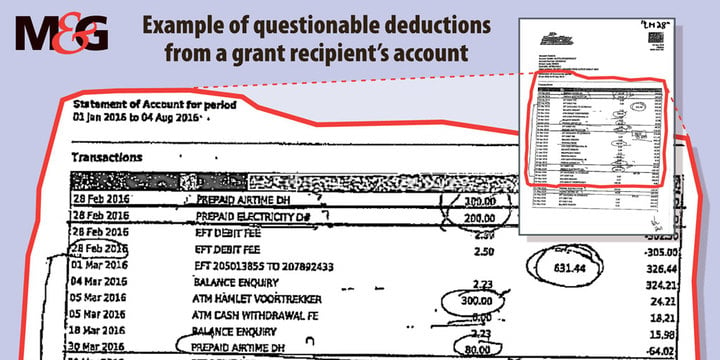

She never qualified for the loan but, after these events, she says she received only the value of one child support grant and many deductions she did not authorise were taken from her EasyPay Everywhere account, including for prepaid airtime and electricity, which amounted to hundreds of rands.

Despite efforts to close her EasyPay account and to stop the deductions, by late last year Bezuidenhout had not been able to solve the problem.

Moneyline is a subsidiary of Net1, the firm at the heart of the Sassa grants contract battle, which is being waged in the Constitutional Court.

EasyPay Everywhere is a transactional bank account, which Net1 offers in partnership with Grindrod Bank and which piggy-backs on Grindrod’s local banking licence. Net1 also works with Grindrod to provide the Sassa-branded card issued to grant beneficiaries, which allows them to transact at ATMs and retailers.

Net1 and its subsidiary, Cash Paymaster Services (CPS), make money from administering grant payments, but the parent company, listed in the United States, has developed an array of financial services offerings that social grant recipients make use of. They include firms offering funeral cover and microloans and the sale of prepaid airtime and electricity.

This business — based on the benefits of “financial inclusion”, according to Net1 — is worth billions. When CPS finally does stop paying grants, be it on March 31 or in a year or two, these are the offerings that Net1 has said it wants to be at the heart of its enterprise.

Bezuidenhout’s tale is contained in an affidavit submitted with an application to the Pretoria high court last year by human rights group the Black Sash, and is awaiting judgment.

As the drama over the Sassa social grants contract now unfolds in the Constitutional Court, this separate but not unrelated legal case illustrates the complex business network Net1 has built around social grant recipients.

According to its recent 2016 annual report, its financial inclusion and applied technologies segment brought in about R3.6-billion, about a 15% growth on the previous period. This is above the roughly R3.1-billion it gets from its South African transaction processing segment, which includes the grants payments.

The Black Sash is intervening for a group of beneficiaries in a battle over changes to social assistance legislation. The litigation brought by Net1 companies and affiliates, as well as other industry roleplayers, against Sassa and the minister of social development, was heard in October 2016. It came after amended regulations were promulgated earlier in the year to deal with unlawful deductions from social grants.

Net1 and its chief executive, Serge Belamant, vociferously deny there is anything untoward about the products offered, and how they are marketed and provided. Investigations by other authorities have found nothing unlawful.

There are also a number of other microfinance firms that operate in this field.

But Bezuidenhout’s experience illustrates the reach the Net1 group of companies has into many beneficiaries’ lives.

The argument between the government and Net1 hinges on the interpretation of the changes to the regulations under the Social Security Act, which are intended to stop unlawful deductions and debits being made from social grant beneficiaries’ accounts.

Sassa interprets the new legislation to effectively mean that no such debits can be made without a beneficiary’s written request for consent. But Net1 disputes this, because it would prohibit it and Grindrod from processing debit orders from social welfare beneficiaries’ bank accounts, and in effect restrict how recipients transact using these accounts.

Net1 is seeking a declaratory order to provide certainty about the interpretation of the regulations or to have them declared unlawful.

But the Black Sash alleges that, in practice, a host of abuses are being perpetuated in the grants system, and the confusing network of roleplayers has hampered efforts to stop them.

Common complaints include beneficiaries being hoodwinked into opening EasyPay Everywhere accounts and told these replace their Sassa cards, and they are not made aware of the associated terms and conditions or of the higher costs associated with the accounts. The terms and conditions include the sharing of confidential information and permitting affiliates and subsidiaries to market their products to beneficiaries.

The Black Sash alleges that beneficiaries cannot tell who is serving them, often assuming that officials who could be from CPS, Moneyline or Net1 are working for Sassa; and that the officials offer and administer loans and other financial services inside Sassa service points, which is against regulations.

Unlawful deductions that defy explanation have proliferated, the Black Sash alleges. For instance, beneficiaries without cellphones have been charged for prepaid airtime.

Sassa’s failure to tender for a new contract for social grant disbursements come April 1, or to bring

the process in-house, means that Net1 is likely to remain intimately involved in grant payouts for at least another year, despite the original CPS contract being deemed invalid in 2014.

This conundrum now rests with the Constitutional Court, which the Black Sash and other civil society groups have asked to reinstate its judicial oversite of the process, including over any interim contract the agency signs with CPS.

Belamant did not respond to questions but in a replying affidavit in the Constitutional Court he refutes the “aspersions” that the Black Sash has made in relation to the high court litigation. Net1 and its subsidiaries do not have “de facto unrestricted access” to Sassa-branded bank accounts, and they are not engaged in unlawful “ambush” marketing practices, he said.

Although its companies and affiliates do market products and services to beneficiaries, this is done in a regulated environment and independently of CPS, he said.

The National Consumer Tribunal and the Competition Commission have been called on to investigate such claims and “properly rejected them as unfounded”, he said.

He added the Constitutional Court should not express an opinion on these matters in its deliberations on the Sassa contract because judgment is pending in the high court and “may ultimately reach this court on appeal”.

Belamant also said CPS is “anxious to avoid becoming embroiled in further protracted and costly legal battles as a result of irregularities that are entirely of Sassa’s making”.

The suggestion by the Black Sash that CPS has “built itself into an impregnable position” and somehow positioned itself to hold Sassa or the state “to ransom” is unsubstantiated, utterly unfounded and unfair”, Belamant said in his replying affidavit.

The South African Reserve Bank, another respondent in the high court matter, has said debit order abuse may be a symptom “of a larger design issue”.

Samples of consumer complaints submitted to the bank may be related to “Net1 being involved in payouts of grants as well of marketing and provision of products or services such as airtime, electricity and loans provided to grant beneficiaries, where beneficiaries appear to have not authorised such services”, it said.

But the Reserve Bank wants the country’s national payments architecture to remain open so that “legitimately contracted debit orders” can be collected. There could be “broader economic consequences” of implementing the regulations, it said. They included problems of collecting on debt legitimately owed, forcing both beneficiaries and creditors to transact in cash, and the potential reversion to illicit and illegal means of collection.

To prevent unlawful debits it recommended beneficiaries be given the option of selecting their own account, and banks should compete to provide this service.

Alternatively a defined basic account could be introduced that enabled Sassa to brand with any bank and to define the basic account and product offerings, including limitations on debit-order deductions.

Meanwhile, in a recent quarterly update, Net1 reported it now has 1.8-million active EasyPay Everywhere accounts. Although anyone can sign up for EasyPay, a large part of its client base include grant beneficiaries. It is not clear how many of the currently active accounts are those of grant beneficiaries or other new customers.

But previous comments made by Belamant suggest that, at least initially, Sassa beneficiaries made up the bulk of these account holders.

In a report by a financial analyst, Jay Yoon, on Seeking Alpha (a platform for investment research), suggested that, as of the second quarter of 2016, about 96% to 97% of them were grant beneficiaries.

The EasyPay Everywhere accounts appear easy to open but the case of Bezuidenhout, who travelled 65km from her home in Prince Albert to Sassa’s and Net1’s offices in Worcester to close her account — to no avail — suggests not everything about the company is easy.