Like South Africa’s major banks

NEWS ANALYSIS

The parliamentary hearings on transformation in the financial services sector come at a time when legitimate concern over the slow pace of transformation has become conflated with political agendas.

Fears about high levels of concentration in the economy have been commandeered by a narrative about white monopoly capital.

The need to address inequality urgently underpins the call for radical economic transformation and, although the financial sector must face its demons in this regard, the matter appears to have been appropriated to serve a sinister agenda that became clear after the politically connected Gupta family’s South African bank accounts were closed.

In opening the hearings on transformation in Parliament’s finance standing committee this week, chairperson Yunus Carrim said the process would be thorough.

“The financial sector is too crucial to the economy to make any immediate decisions but, on the other hand, things can’t stay as they are, even if there have been some improvements since 1994.”

Various parties provided input on the matter.

The submission by the Banking Association of South Africa (Basa) outlined the progress made in the sector and highlighted how banks have exceeded some key targets set by the Financial Sector Charter. These include employment equity targets, procurement and enterprise development targets, empowerment financing, direct ownership and access to financial services.

But the department of trade and industry submitted that the level of compliance with the charter in the sector as a whole is low. The treasury said that the charter’s targets are not ambitious enough.

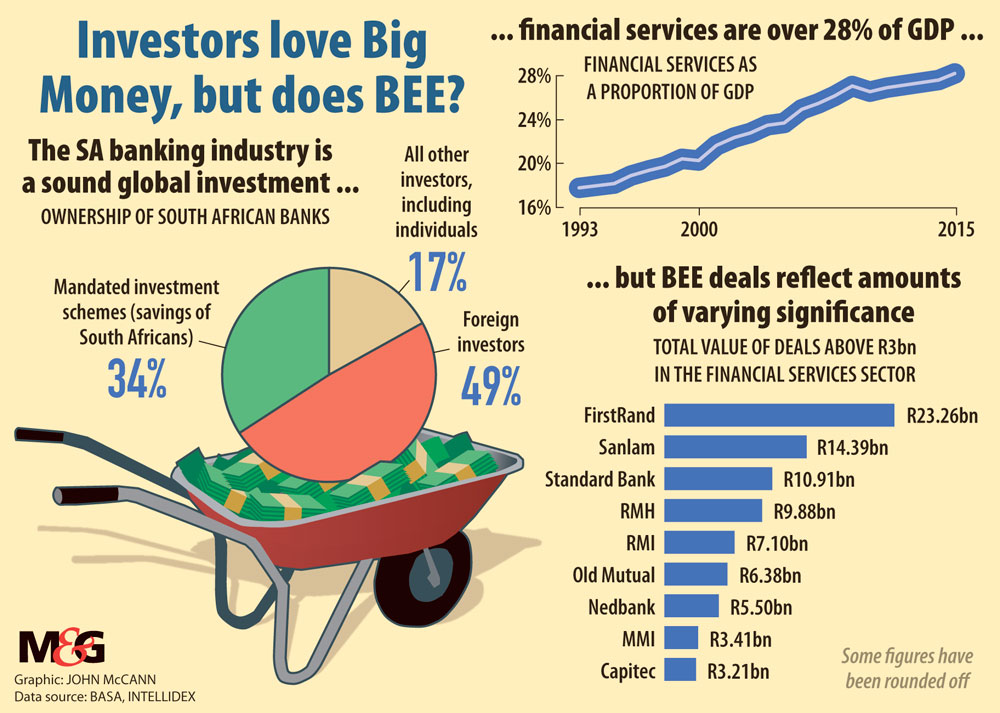

Trade union federation Cosatu raised several concerns, including the high level of foreign ownership in South Africa’s major banks.

Basa acknowledged that the largest share of the top six South African banks is owned by foreigners (49%), followed by mandated investment schemes (34%) such as the state-owned Public Investment Corporation.

“These ownership patterns are not limited to banks, as the top 100 companies listed on the JSE also reflect a similar trend,” Basa said.

Intellidex, a capital markets and financial services research house, said the JSE is a major source of funding for banks and insurance companies and provides important protection in the event of distress as it is the funders, not the depositors, who stand to lose.

It added that the raising of other funds from bonds and preference shares provided further layers of protection for depositors should there be a crisis. “[Also,] foreign providers of capital are essential to South Africa’s development because of the low domestic savings rate.”

South Africa’s financial infrastructure makes it possible to deliver funding solutions that would otherwise be impossible, such as “notional financing”, in which black economic empowerment (BEE) schemes can gain exposure to shares without the immediate cost of financing, it said.

“There has been significant wealth creation among black beneficiaries specifically because of this form of financial engineering,” Intellidex said.

“As the distribution of wealth in South Africa normalises, it is a natural consequence that the profile of investors on the JSE will normalise. On this view, black ownership of JSE-listed companies is a consequence rather than a cause of transformation.”

Although the success of BEE transactions is often viewed in terms of the black ownership of companies, Intellidex said beneficiaries usually dispose of these shares and so do not become long-term shareholders.

“This is a rational outcome. It does not make sense for individuals to hold concentrated equity exposures. They should rather diversify their portfolios in order to balance risk and return.”

As such, Intellidex argued, it is more important to measure BEE deals in terms of the wealth they create rather than long-term ownership. Its data shows that, as of 2015, BEE deals by the banks generated R57‑billion in value for beneficiaries.

But in its submission, Basa said a choice must be made between the financing of black ownership and increasing financing in the real economy.

Ownership deals are financed by banks but that is inefficient for the economy as it cannot be leveraged. And, because banks are also required to reserve capital, “what this actually means is that, for every R10 of capital a bank uses to finance a new black shareholder, approximately R80 is removed from financing a black business”, Basa said.

Credit extension in South Africa is a similar percentage of gross domestic product as in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, meaning South Africans are able to access credit services as easily as the citizens of more developed countries.

But the costs of finance and banking fees remain a bone of contention.

Cosatu expressed concern about “exorbitant bank charges and interest rates”, which it said the “Twin Peaks” or two-pillar model of financial sector regulation did not go far enough to rein in. It argued that those who can least afford debt repayments are charged the highest interest rates when they should be charged the least.

“How does treasury expect workers to save when they are offered below-inflation interest rates for savings? More so when the same banks never miss a chance to charge consumers ridiculous bank charges,” it said.

Basa said banks have to navigate a complex web of domestic and global regulations and standards, which have been adopted since the global financial crisis of 2007. Compliance with these could result in a direct cost to customers, it said.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian, Basa chief executive Cas Coovadia said that South Africa’s fees compared favourably with those elsewhere. Basa conceded progress had been slow at board and executive levels and on targets for black executives, and the number of black women in senior management positions had also fallen short of targets.

The financial services industry “is one of the best tools we have to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality”, Intellidex said in its submission. “If we decide that it is unavoidable that some policies will weaken financial institutions, we must be confident that this cost is worth it.”

The hearings are continuing.

Push innovation in pursuit of economic change

Capital markets and financial services research house Intellidex has offered ideas about how the private and public sectors could together promote the financial inclusion of black businesses and individuals.

Black borrowers are often at a disadvantage compared with white applicants, who are often more able to offer collateral and can therefore access a lower cost of financing.

The government’s Reconstruction and Development Plan housing project has built three million homes since 1994, but the backlog in awarding title deeds delays the transfer of wealth to the intended beneficiaries. Eliminating this backlog would immediately provide collateral and access to lower-cost financing, Intellidex suggests.

“That collateral could be made even more valuable by driving the development of rural and township-based property markets.”

Targeted financing to black borrowers should be an important part of transformation commitments for institutions and targets should be set, the research house says.

Infrastructure bonds are another avenue, to harness the government’s risk-absorbing capacity to drive financial institutions to fund infrastructure that alleviates poverty and inequality.

This week, Black Business Council secretary general George Sebulela recommended to Parliament’s finance standing committee that institutions should be at least 51% black owned before any new banking or insurance licence is issued, and that black ownership must also be a JSE listing requirement.

“This is not business as usual. This is a warning of something larger, and the sooner we realise it, the better,” said Sebulela.

“What we are witnessing is the birth of a new politics of legislative activism. We are witnessing the birth of radical economic transformation. Only radical change can save our country.”