Scenes from the Constitutional Court this morning.

NEWS ANALYSIS

As the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) prepares to interview candidates for a vacancy in the Constitutional Court, political storm clouds are gathering. At this point, we don’t even know which Cabinet member will be sitting on the left of Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng to represent the executive at the JSC.

Justice Minister Michael Masutha is unwell and Communications Minister Faith Muthambi is acting in his place, making her, in law, the person who should be sitting on the JSC. Questions put to the justice department on whether she would attend or send an alternate went unanswered this week.

With the government so unstable, and with Parliament largely failing to hold it to account, the courts have emerged as a steadying hand on South Africa’s democracy. The judiciary has also been called on disproportionately to be the bulwark against government abuse of power. Courts have been dragged, often uncomfortably, right into the centre of political battles.

This makes every one of the 11 justices sitting on South Africa’s highest court crucially important.

Just this week the high court in Pretoria has been the battleground for the staring contest between the Guptas and Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan. Earlier this month, the ConCourt was forced to step in to avert an impending disaster over the payment of social grants.

The interviews, scheduled for Monday to Thursday, will be held at the office of the chief justice, the scene of a suspicious break-in, which gave every appearance that the thieves were looking for specific information.

All this is likely to cast a pall over the interviews. But this is not a new thing. The 2015 round of ConCourt interviews happened in the wake of the government’s apparent brazen defiance of the rule of law when it allowed Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir — wanted by the International Criminal Court — to be spirited out of the country despite a court order that he should not be allowed to leave.

Candidates were closely questioned on the subject, and their interviews often became a platform for Mogoeng and Masutha to spar on this issue. It was mostly polite, but tense.

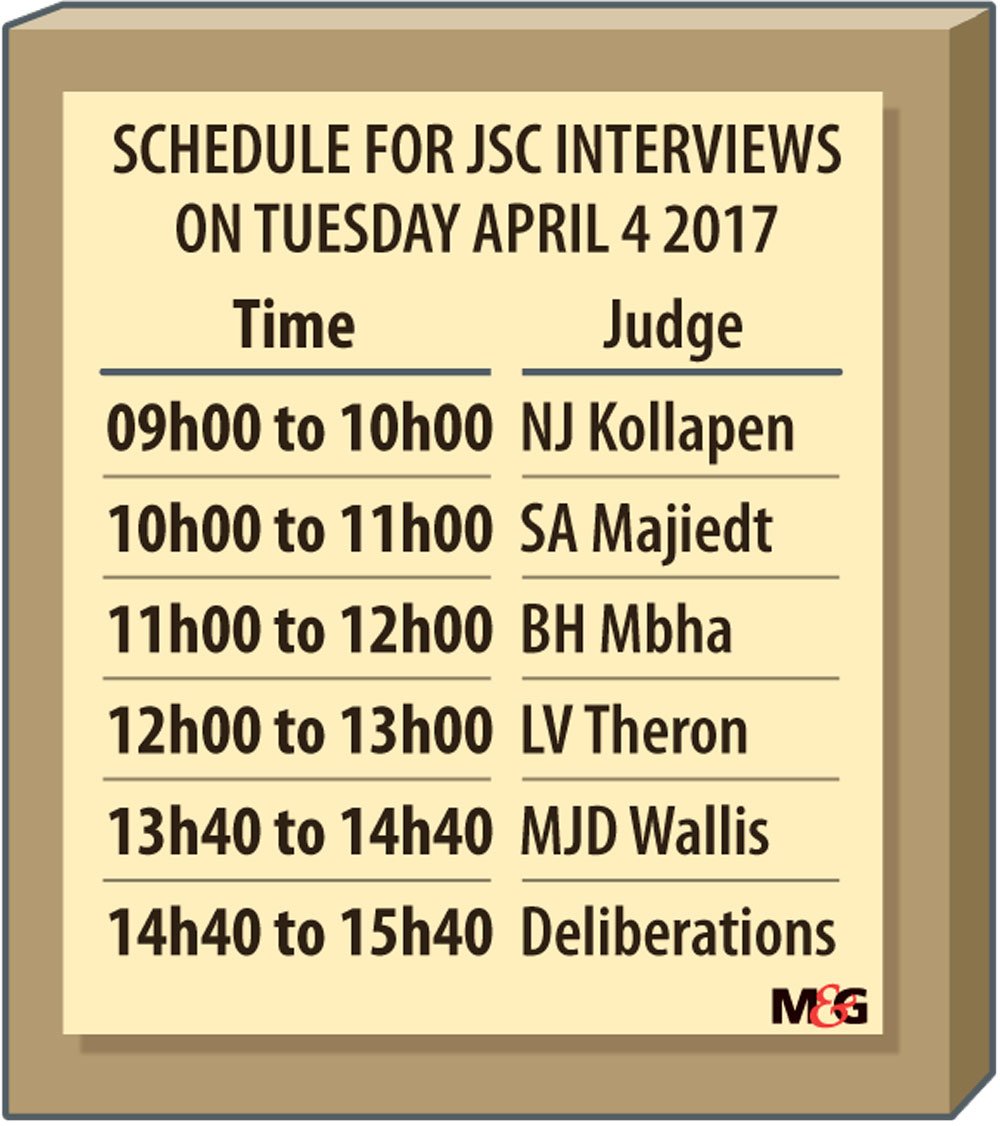

On Tuesday, five candidates will be interviewed for the position. This follows a prolonged vacancy after Justice Johann van der Westhuizen retired in January last year. In seeking to fill the post, the JSC first had to readvertise the position because of an initial lack of interest.

Then, when it managed to scrape together a shortlist of just four (the minimum number according to constitutional requirements), the interviews — scheduled for October last year — fell apart when Supreme Court of Appeal Justice Ronnie Bosielo was forced to withdraw his candidacy after a complaint was made against him.

This time round, the list is longer and it is stronger. The candidates are Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) justices Leona Theron, Malcolm Wallis, Stevan Majiedt and Boissie Mbha and high court Judge Jody Kollapen.

But, for ConCourt appointments, the power really lies with the president. Under the Constitution, the JSC’s job is to provide a list of names to the president — three more than the number of positions being interviewed for. The president then makes his choice from that list.

With only five candidates to be interviewed, the JSC’s role will be limited to pruning one name from that list.

The president’s track record on appointing women judges is not a good one. At the Kliptown interviews in 2009, there were four vacancies, but he chose to fill only one with a woman candidate, overlooking respected SCA Justice Mandisa Maya. At the 2012 interviews, he once again overlooked Maya.

This time, he has nominated Maya to be president of the SCA, making her the first woman to fill this senior post. But he has already been criticised for not selecting a woman justice to fill Dikgang Moseneke’s shoes as deputy chief justice.

Though Justice Bess Nkabinde is due to retire at the end of 2017, Justice Sisi Khampepe has served longer at the country’s highest court than the president’s choice, Justice Raymond Zondo.

Maya and Zondo will be interviewed by the JSC on Monday for their respective posts.

Theron is the only woman candidate nominated for elevation to the ConCourt in this round. With Nkabinde about to retire, the court is likely to go backwards in terms of gender transformation, leaving just two women justices — Khampepe and recently appointed Nonkosi Mhlantla — on its Bench.

The Constitution requires the JSC to consider the need for the judiciary to reflect South Africa’s population broadly in terms of race and gender. But the ConCourt, the ultimate guardian of our equality rights, has consistently been one of the worst performing courts in terms of gender. It has never had more than three women justices.

This should, on its own, put Theron in a strong position. She is also the most senior of all the candidates; she was appointed to the high court in 1999 and elevated to the SCA in 2010.

Theron, the first in her family to get matric, was appointed a judge at the age of 33.

A popular candidate among lawyers, she was praised by the African Legal Centre for the judgments she penned during her acting stint at the ConCourt in 2015.

One of these was the Molaudzi case, which the centre described as “a thoughtful consideration of when a court has the power to relax procedural rules to prevent manifest injustice”.

The centre said her “obvious lawyering ability, and her impressive work rate and tenacity, have won Theron many admirers”.

Thembekile Molaudzi had been arrested after a police officer was killed. He was freed after 10 years in jail after his conviction was overturned by the ConCourt.

Theron would also be the first coloured judge to be elevated to the highest court. During her 2009 interview in Kliptown, she was asked whether there were any coloured justices at the SCA, where she had been acting. In an awkward and quintessentially South African exchange, she shyly asked whether SCA president Lex Mpati was coloured, saying she wasn’t sure.

Mpati responded jokingly that he was “ ’n tussen” — “I grew up in that circumstance when I’m amongst coloured people, they would say I am an African, and when I’m in an African group, they’ll say you’re a coloured.”

Majiedt follows Theron in seniority — appointed to the high court in May 2000 and to the SCA in 2010 — and would also be the ConCourt’s first coloured justice, if appointed.

He is best known for being one of the panel of appeal court justices who found Oscar Pistorius guilty of murder, overturning the high court’s culpable homicide verdict.

One of the favourite candidates of the legal community, while acting on the ConCourt, he penned the ground-breaking judgment that found that the South African police had a duty under international law to investigate allegations of torture by Zimbabwean police and rejected the argument that a good reason to refuse to investigate was the potential harm to South African-Zimbabwe political relations.

But a report by the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit says another of Majiedt’s ConCourt judgments, the Hubbard case, has been the subject of academic criticism — by Wallis, now coincidentally also up for the same post.

The case dealt with housing consumer protection laws and when arbitration awards should be made an order of court. Majiedt had the support of the majority of the ConCourt, but in a legal academic journal Wallis said his approach created uncertainty and cast doubt on long-standing legal principles.

Wallis, a known stickler for legal rigour, is viewed as the lawyers’ lawyer. Although appointed a judge later than the others, at the time of his appointment he was considered one of the best silks in South Africa.

As an acting judge on the ConCourt, he was part of the bench who decided the famous Please Call Me case, in which MTN was ordered to negotiate in good faith with Nkosana Makate to compensate him for his innovation. Makate came up with the Please Call Me idea, which had made billions for MTN but for which the innovator was yet to see a penny.

The judgment was widely hailed for bringing justice to Makate, but also led to some dismay in the legal community for what it meant for the law of ostensible authority and prescription — technical but crucial areas of law. Some lawyers said they had been distorted or made uncertain by the approach of the ConCourt.

In what one lawyer called a “valiant effort”, Wallis penned a lengthy separate concurring judgment on ostensible authority — to arrive at the same conclusion using a different legal route.

Appointed to the SCA in 2011, after just two years on the Bench of the high court in Durban, he penned the judgment that confirmed the government had acted unlawfully when it failed to detain al-Bashir when he visited South Africa in June 2015.

He also has moments of apparent judicial humour. In his judgment on the #FeesMustFall “Shackville” students at the University of Cape Town — interdicted by the high court from setting foot on campus — he had to decide whether “fuck white people” amounted to hate speech.

It did not, he decided, adding: “It is regrettably not uncommon for people to use strong language in which, as Van den Heever J once delicately expressed it, ‘a word signifying the sexual act [is] substituted for a verb of motion’.”

Wallis is the only white male candidate in this round of interviews and it remains to be seen how this will play out in the interviews and selection. There are two white male justices on the ConCourt Bench — Johan Froneman and Edwin Cameron — the smallest number since the court was established.

Mbha was appointed to the high court in 2004 and to the SCA Bench in 2014, and is described as a respectable all-rounder by lawyers.

While acting at the ConCourt he penned the Laubscher judgment, which dealt with whether same-sex partners who had not entered into a civil union could inherit from each other in the absence of a will.

For the majority, Mbha found that same-sex partners could inherit from each other, even if there was no will and even though they had not entered into a civil union.

But the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit said his judgment was nonetheless criticised by academic Pierre de Vos, who took issue with the judgment referring to same-sex marriages concluded in terms of the Civil Union Act in inverted commas as “marriages” or as civil unions — “as if such unions are not fully fledged marriages that are identical to different sex marriages”.

Described by Mpati as “sort of a fitness fanatic”, Mbha has run the Comrades Marathon six times and has a black belt in karate.

In his JSC interview in 2014, he said he had tried his hand at boxing. “I wasn’t very good at it, I’m afraid.”

Kollapen was appointed to the high court in 2011 after heading the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC). Of the candidates, only Kollapen has not acted on the Bench of the highest court and is not an appeal court judge, which may put him on the back foot.

Having acted is not a requirement but it is widely viewed as an advantage. A human rights activist from the beginning of his legal career, he is most well known as a commissioner and chairperson of the SAHRC from 1997 to 2009.

He is known for taking a human-rights bent in judgments, even when they are not directly implicated. As a high court judge, Kollapen found that the government had breached the right to education in failing to deliver textbooks to Limpopo schoolchildren.

He also dismissed AfriForum’s challenge to the language policy at the University of Pretoria, saying the need for redress, the advancement of equality and the imperatives of transformation had to be considered.