(John McCann)

NEWS ANALYSIS

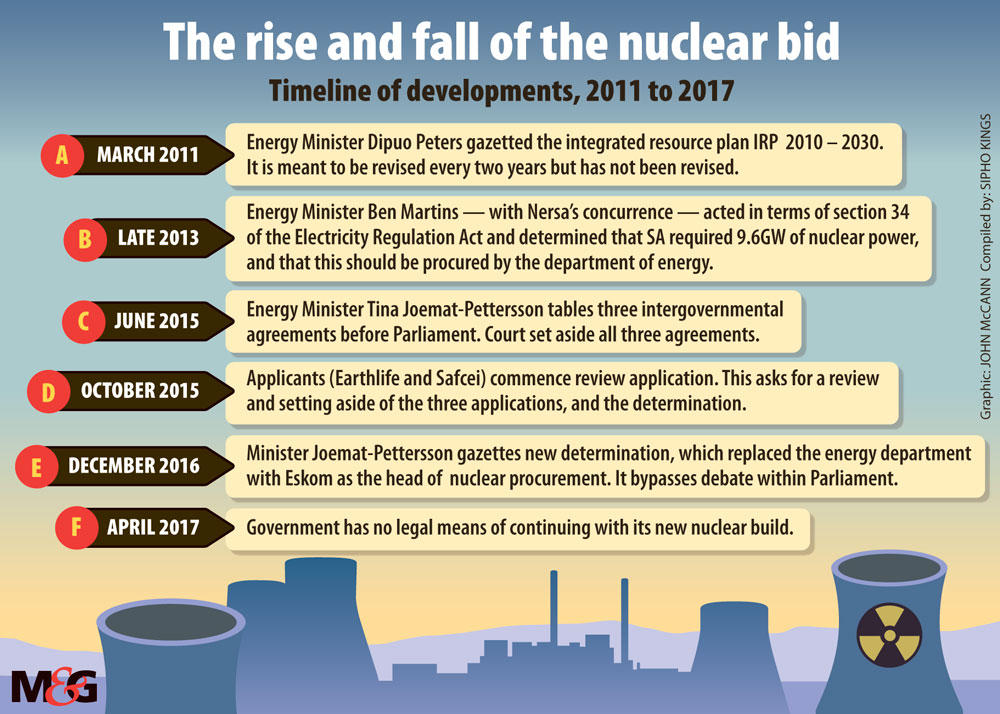

The Western Cape High Court has all but ensured that South Africa will not build nuclear energy under a Jacob Zuma presidency.

In its Wednesday judgment, the court set aside three intergovernmental nuclear agreements, signed with the United States, South Korea and the Russian Federation. It ruled that the tabling of these before Parliament had been unlawful and unconstitutional.

The Russian deal has been mired in controversy. It was signed in September 2014, three weeks after Zuma held talks with Vladimir Putin in Russia. Details of the deal emerged in a Mail & Guardian report in February 2015. One of its provisions indemnifies Russia from liability for any nuclear accidents.

Two finance ministers, Nhlanhla Nene and Pravin Gordhan, questioned the affordability of a nuclear build. Commentators speculate that this is why they lost their jobs.

The drive for nuclear energy has been cited by ratings agencies as a major reason for credit downgrades, because the reported R1-trillion cost would be carried by Eskom and backed by the state.

The high court has now set aside the 2013 and 2016 section 34 “determinations” by the energy minister as unlawful and unconstitutional.

Those determinations allowed Eskom and the energy department to invite companies to bid to build 9 600 megawatts, the equivalent of the capacity of both the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations.

By throwing out these determinations, the court has sent the government back to the drawing board. The energy department has said it is studying the judgment and has not indicated whether it will appeal. If it does, the environmental groups involved in driving the case can ask the court for an execution order, which would ensure that its ruling stands until an appeal is heard. Legal experts say it is probable that an execution order would be granted.

If the government does things properly, as the judgment outlines and in accordance with international agreements, it will take years before South Africa can start a new nuclear build.

It will have to draw up a new determination and send that through to the National Energy Regulator (Nersa) for authorisation. The regulator will then have to hold a meaningful public participation process that will be scrutinised before signing off on the determination.

After all this, the entire basis for the nuclear build could be undermined by an impending update to the country’s energy plan — the Integrated Resource Plan.

The 2010 version of this plan gives the government its justification and legal basis for pursuing new nuclear power. Based on projections about power demand and economic growth, it said South Africa would need to build 9 600MW of nuclear capacity. The plan is supposed to be updated every two years, to reflect economic realities and the status of alternative energy sources.

A 2016 update has just passed the public consultation phase. Its draft base case says no new nuclear is needed until 2037, with one scenario excluding nuclear as an option. A policy-adjusted near-final version ought to be promulgated in about September.

When it does come into effect, it will be the legal energy blueprint for South Africa. This may mean there will be no basis for the administration to procure new nuclear power.

The widely held view in energy circles is that nuclear was pushed through to ensure it fell under the 2010 plan. A 2013 update, which favoured energy choices of “least regret” and said no decision on nuclear needed to be made until the mid-2020s, made it to Cabinet but was shelved. This could also happen to the 2016 update.

But civil society groups have indicated that this move would quickly end up in the courts.

For now, the Western Cape judgment has reset the clock on nuclear energy. Nongovernmental groups Earthlife Africa and the Southern African Faith Communities’ Environment Institute approached the court in October 2015, asking it to set aside the agreement with Russia.

This went into detail about a nuclear build, mentioning the use of reactors solely supplied by Russia’s state nuclear utility, Rosatom.

At that point, South Africa did not have a legal process with which it could turn that agreement into something practical, because there was no gazetted section 34 determination.

The background work for such a determination had been done in 2013, when the energy department went as far as getting the required permission from Nersa to build 9 600MW of new nuclear capacity, but it was not been gazetted. In December 2015, the energy minister used this work as the basis for gazetting a section 34 determination.

The same process was followed in 2016, with an updated determination that took oversight of the nuclear procurement process from the energy department and gave it to Eskom. It did not repeal the 2013 determination, which the court noted meant both state entities were legally in charge of the nuclear build.

“This resulted in an anomalous situation of there being two gazetted section 34 determinations which are mutually inconsistent.”

The court said the energy regulator had signed off on the 2016 determination in just three days. This was despite the big change in who would oversee the build. In the ruling, Judge Lee Bozalek said: “It was, in my view, incumbent on the regulator to afford members of the public and/or interested and affected persons an opportunity to influence the decision.”

Because this had not happened, and because it had been so long since the 2013 determination had laid the groundwork for its successor, the court ruled that both determinations were unconstitutional and unlawful, and “violated the requirements of open, transparent and accountable government”.

It then looked at the three international agreements signed with Russia, the US and South Korea.

In the case of the Russian agreement, the energy department had managed to circumvent debate in Parliament by using section 231(3) of the Constitution. This allows government entities to merely table agreements in Parliament, without debate. This section only works for “technical, administrative or executive” agreements.

In its defence, the state argued that the Russian agreement fits this requirement. It also attempted to argue that, because it was an international agreement, it could not be heard in a domestic court.

The court disagreed: “The minister’s obligations to act constitutionally and in accordance to section 231 are owed to the citizens of this country and not to foreign governments.”

The applicants said the energy department should have used subsection (2) of section 231. This would have forced it to table the Russian agreement before Parliament, which would have to approve it before procurement could go ahead. The court agreed, saying that the “detail and ramifications” of the Russian agreement in particular “are such that it clearly required to be scrutinised and debated by the legislature in terms of section 231(2) of the Constitution”.

Bozalek then dealt with former energy minister Tina Joemat-Pettersson, saying: “At best, the minister appears to have either failed to apply her mind … or at worst to have deliberately bypassed its [section 231’s] provisions for an ulterior and unlawful purpose.”