The community at the Goudkoppies dumping site in Devland opposite Eldorado Park township make a living out of recycling.

“We don’t live here because we like being dirty, it’s a place to work. If you can’t see, this is a factory. Even the recycling companies know it,” said Alfred Chilwane, one of the most respected residents of the Goudkoppies informal settlement.

Goudkoppies – built on top of the Devland dumping site – has re-emerged bigger than before after residents rebuilt their shacks and refused to relocate, after evictions by the City of Jo’burg last year. Last week residents of Goudkoppies described the area as a bustling marketplace for the informal recycling trade and a home in a foreign country.

They say they rebuilt the cluster of shacks and workshops because the settlement is actually an informal recycling factory, home to thousands of Johannesburg’s scrap collectors and Southern African migrants.

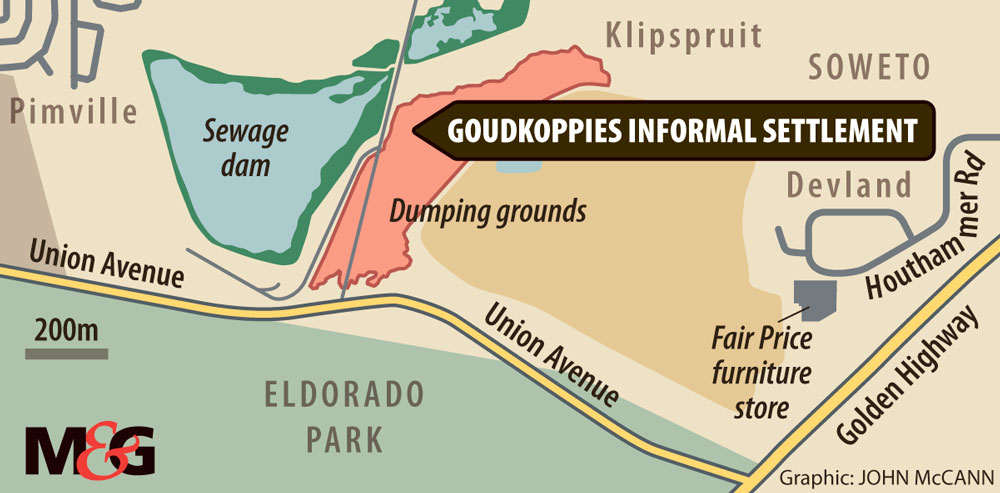

The settlement is located on the foot of the Goudkoppies landfill between Eldorado Park and Devland. Despite the omnipresent human waste, sewage and discarded rubbish, it started attracting illegal immigrants and homeless South Africans in 2010. Since then, the settlement has extended across most of the vacant land between the landfill and a sewage treatment plant and is now home to more than 5 000 people.

The city of Jo’burg has experienced a 7% growth in paper recycling over the past four years, according to the Paper Recycling Association of South Africa. The association projects that the city would be recycling 63% of its paper by the end of 2017, placing it ahead of the global average of just 1.5%.

Chilwane is considered the “madala” of Goudkoppies. In the absence of any law and order and with a tense mix of South Africans and foreign nationals from Lesotho, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Tanzania, the 54-year-old acts as a mediator during disputes. Police regularly pass through the settlement on patrol, though Chilwane claims they have earned a notorious reputation.

“You have to keep your wits about you here. There’s no government or clinic but there’s work. You see these police, they just come get rich from bribes but don’t do anything about crime,” Chilwane said.

“If you recycle then this place is a workshop, not a place to stay. Everything is on its place and everyone does their work,” Chilwane added.

Chilwane and his three sons work a section of the settlement where brown and green glass bottles are separated into different sections. Brown bottles are worth R0.20 a kilogram and green bottles a little more.

“Me and my sons have had this workshop for seven years. We only pack plastics and glass, we separate it you see. But it’s not even enough to survive,” Chilwane said.

The Johannesburg metro police, Red Ants and Eldorado Park community members tore down the shacks and set fire to the dump in April last year. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) conducted an inspection of the Goudkoppies settlement in 2015 and found more than four thousand people living without fresh water, electricity or sanitation.

The cleanup was the result of the SAHRC report as well as a petition from Eldorado Park residents who complained about the pollution in their suburb, caused by the informal recyclers burning rubber off the cables to get to the copper.

But “it took us less than a year to build it up again”, says Chilwane, shaking his head at at what he called the “ruthless and hateful” manner in which the evictions were conducted.

“Horses, JMPD vans, Red Ants; they were just quick and didn’t care. They broke down everything and they burnt the shacks that were too close to the road. Now we aren’t allowed to pass these electric poles,” Chilwane says, while pointing to the electricity pylons which tower above the shacks and remind residents of the new boundary.

At the entrance of the township, informal recyclers set up mini workshops with up to three people sorting the rubbish and weighing the valuable scrap with an electronic scale, estimated to cost R2 500 and the most sought-after piece of equipment in the settlement.

Lionel Smith and Clayton van Rooyen, both originally from Kliptown, live in a shack near the entrance and begin their day by cleaning out the motor of an old engine and stripping the rest of it. The pair fled life of the streets four years ago in search of a “stable job and some security” in Goudkoppies. They are employed by two men from Eldorado Park who pay them up to R300 a week for sorting plastic and glass and finding and cleaning mechanical equipment.

“You see here I learnt a new trade. Anything to do with stripping or cleaning engines and motors, or getting the copper parts of electronics, I can do. But to tell the truth, this is keeping us away from the prison gates and out of trouble like robbing and stealing, you know,” van Rooyen told the Mail & Guardian.

The pair also collect boxes and glass and stockpile their work in large recycling bags.

“We are not dumb, you see. We fill up this 200 kilogram bag and only then take it to the [Remade Recycling] trucks so we get a lekker score. It takes about a full day or day and a half,” Smith explains.

The two men who employ them arrive at the site every Monday morning and while they don’t want to be identified, said they started their own small scrap yard, where they collect material from informal recyclers like Van Rooyen and Smith, and sell it to bigger companies for more money.

“Companies like Nampak and Remade Recycling, they basically send trucks to collect the scrap and it works. At least this way I can put something on the table for Lionel’s mom who is still in Kliptown and keep him out of trouble and put money in his hands,” one of the men told the M&G.

The residents coming from Lesotho have occupied a strip of land on the edge of the sewage water treatment plant where they stockpile plastic and boxes. These can be sold for up to R2 a kilogram.

At 4 o’clock in the morning Sibusiso Radebe of the Goudkoppies dumping site started pushing his scrap collecting trolley from the informal settlement on the edge of Eldorado Park. He usually only makes it as far as Orlando West, but strives to reach the city’s suburbs, in search of metals, plastic, cardboard, glass and the more valuable aluminium, copper and brass.

A day’s work earns him anything between R100 and R150 from recycling companies that routinely arrive at the site to collect neatly sorted and packed materials. But Radebe prefers to stockpile the scrap he collects, and said he earns up to R1 800 a month in this way.

The 24-year-old admits to giving a false name, he’s an illegal immigrant from Lesotho who has been living on the dumping site for just under four years and fears having his face captured on film or his name released to the public. His main reason for living in the filth, he says, is the “factory set-up” and potential to earn a living.

“Goudkoppies already has sections where you can put plastics, glass, or just scrap. It’s so easy to work and people come here to work, not to mess around. You can make money here,” he says, with his face covered by a balaclava and his one hand firmly gripping the trolley carrying the day’s work.

“There are so many people from Lesotho here. At least I can feel safe because we don’t see eye to eye with South Africans,” he adds.

Closer to the middle of the settlement, disused plastic TV covers, metal from mattresses and even discarded hosepipes are being cut up and sorted for collection in another workshop. But the more precious metals, brass, copper and aluminium, worth R30, R50 and R10 a kilogram respectively, are hardly sighted.

This is due to its high return value, explains Sheldon Le Port, a former Eldorado Park extension 5 resident who moved to Goudkoppies when it first started seven years ago.

“Where are we going to find the copper and brass brother? I’ve been here since the beginning but these days it’s more difficult to find that kind of stuff. You must basically strip motors or steal,” Le Port explains, shaking his head when asked about other informal recyclers burning what appears to be electricity cables to get to the copper.

Each of the informal recyclers fiercely guard their workshops and the scrap and plastic they’ve collected, as armed robberies are commonplace and usually happen in the middle of the night.

Zimbabwean migrant Phineas Mlambo (27) was the latest victim of a violent robbery that took place on Easter Friday.

“They came in the middle of the night and I heard them taking my work and looking for the scale. When I tried to scare them with my voice they collapsed the shack on me where I was sleeping and hit me with a steel pipe,” Mlambo explains.

“They took the scale but didn’t find the [electronic] head – so it was useless. I found the scale here [in Goudkoppies] again,” he adds.

Chilwane explains that many of the migrants from Southern African countries often arrive at the dumping site with their entire families, who stay in a cluster of shacks in the middle of the site. Workshops for informal recycling encircle them.

The residential area boasts a spaza shop and a Chesa Nyama takeaway where groups of men huddle to eat pap and gravy in the morning, before heading out to try and collect recycling material.

Goudkoppies also has its own barber shop and attracts businessmen in BMWs trying to make some money off the informal factory workers’ labour.

Moshoeshoe Monyane said she had been living in Goudkoppies since 2015 and has two young children aged 3 and 5. Monyane left Lesotho in search of a job in Johannesburg but hasn’t been able to find any work outside of preparing food for the men at Goudkoppies and doing hair for the women.

The 32-year-old said life in on the dump can be described with the words danger, illness and exploitation.

“Electricity, toilets and running water we don’t have. We must go to the [sewage water treatment] plant to find a pipe which is leaking for water. When the copper burns it damages our lungs and even when police come they want tjo-tjo money. We have many problems,” Monyane said.

The settlement of homeless people on dumping sites is not unusual in South Africa. Similar informal settlements have been found in the Blue Crane municipality near Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape and in Moreleta Spruit east of Pretoria in the city of Tshwane.

But, as Smith says, Goudkoppies is the “the most organised of them all”.

“People from other dumping sites come here because we don’t play here, we work. You can make a living,” Smith said.

But he admits to feeling ostracised by a society which considers his job dirty.

“If only people in the suburbs can remember that we are actually in business with them. We sort and recycle the stuff they throw away. So if they can just separate glass from plastic and boxes it will be a great help,” Smith pleads.

“[But] of course I don’t think they will. They still pull their noses up when other recyclers go through their Pikitup bins looking for stuff for the trolleys,” Van Rooyen adds.