Labour intensive: The government would not want to see mineworkers on the march in Marikana should Lonmin crash. This increases the likelihood of the PIC becoming the majority shareholder.

If the state does ever opt to own South Africa’s mines, it may have to start with Lonmin. It’s already the largest shareholder in the embattled platinum producer through a 30% stake held by the Public Investment Corporation (PIC).

With speculation rife that Lonmin may have no choice but to undertake another rights issue to raise money, investment analysts have not ruled out the possibility that the PIC could be called upon to rescue the company again.

Lonmin’s 2015 bid to raise cash, underwritten by the PIC, was undersubscribed, which saw the PIC taking up the unsold shares.

Under company law, if a person or company acquires a number of shares in a JSE-listed firm that pushes it over a shareholding threshold of 35%, that person or company has to make an offer to buy out the remaining shareholders.

The rights issue has tided Lonmin over while it restructured extensively and cut jobs to keep afloat during a downturn in commodity prices.

In January, a disappointing production update revealed that Lonmin is burning up the cash rapidly because its costs to mine the platinum group metals are outstripping the metals’ prices. Productivity declines have been compounded by high levels of worker absenteeism, most notably on one of its most important shafts.

Lonmin declined to respond to questions because it is releasing its interim results on Monday.

These issues come at a time when the government and the ruling party are pushing for so-called radical economic transformation and amid renewed demands to nationalise the country’s mines, most notably by Chris Malikane, Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba’s new adviser.

“Their [Lonmin’s] previous rights issue just gave them time,” said Wayne McCurrie, the fund manager of Ashburton Investments.

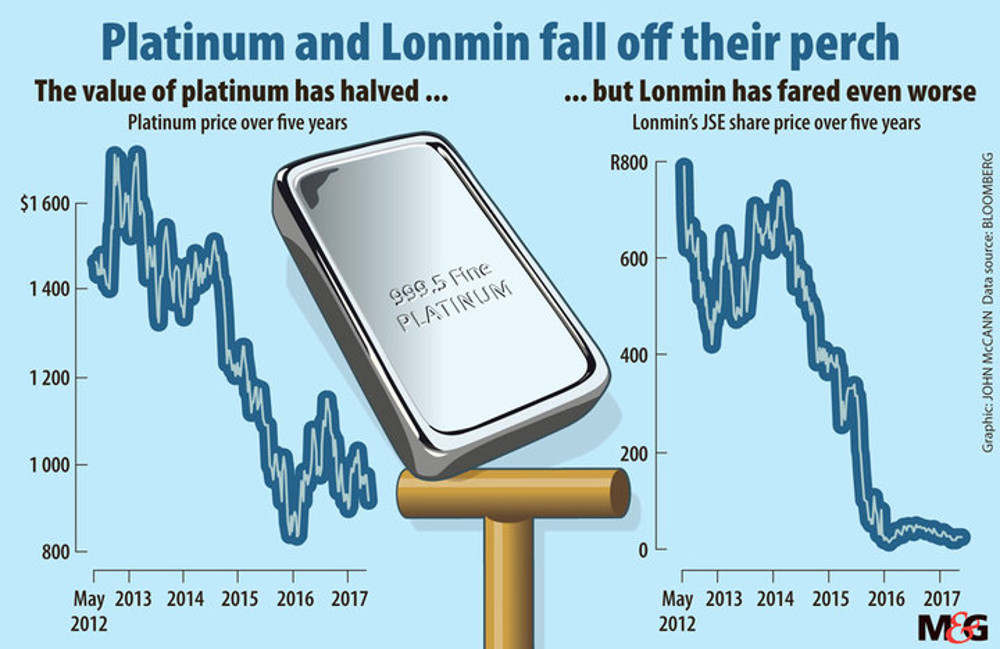

Unless the platinum price rises to about $1 200 an ounce, “it is just a question of time before they need another rights issue”, he said.

By Wednesday this week, the platinum price was hovering at just over $905 an ounce; the rand price was at about R12 225. This is just shy of the R12 296 unit production cost that Lonmin spent to mine platinum group metals (PGM) in the first quarter. But it is well above Lonmin’s goal of achieving costs of between R10 800 and R11 300 a PGM ounce for this year.

At these prices, local platinum producers are losing money, though there is a question of how much, McCurrie said.

Lonmin has to mine deeper than the other mines for lower grades of platinum and it is the most marginal of the platinum mining companies, he added. “Unless the price goes up, they will continue to lose money.”

Lonmin employs more than 25 000 permanent workers and almost 7 500 contractors.

Given the history of the area and the 2012 Marikana tragedy, it is unlikely that the PIC and the government will let Lonmin fold because of the potential political fallout, McCurrie said.

If the other shareholders balk at another rights offer, the PIC would probably underwrite it and become the majority shareholder — resulting in a state-owned mining company running at a loss, he said.

Duma Gqubule, the director of the Centre for Economic Development and Transformation, agreed and said the PIC might not want outright ownership of Lonmin but it might well end up with it. To protect jobs, “the PIC would likely have to dip into their pockets” until the platinum price recovered, he said.

If Lonmin is in trouble, it is only a matter of time before the other platinum producers are in trouble, and the government should be thinking about ways to protect a strategic industry, he said.

In a recent report, Gqubule criticised the limited transformation of the sector, calling for radical state intervention based on the Norwegian model.

One recommendation in the report was consolidating the PIC‘s and the Industrial Development Corporation’s (IDC) mining assets into a professionally managed sovereign wealth fund, which could be listed on the JSE. The state owns about 15.7% of the value of local mining assets through the PIC and the IDC, according to the report.

Much depends on the long-term future of platinum. Oversupply is a long-standing constraint and, said McCurrie, above-ground stockpiles are estimated at between two million and five million ounces of platinum.

Peter Major, the director of mining at Cadiz Corporate Solutions, believes Lonmin is almost certainly going to have another rights issue, “and the PIC is going to have to follow their rights — and possibly more — if they want it to be successful. They may not want to, but government is unlikely to want 25 000 mineworkers marching in the streets.”

There was a widespread belief that Neal Froneman’s Sibanye Gold would make a bid for Lonmin, but Sibanye’s acquisition of the only United States-based PGM producer, Stillwater, has put paid to this.

When asked if Sibanye would consider acquiring Lonmin, Sibanye’s investor relations head, James Wellsted, said his company already has assets adjacent to Lonmin and, from an operational and regional perspective, it would make sense. But the conditions would have to be right, both in terms of the price and in what kind of position Lonmin is in terms of its capital needs.

“The other thing we have highlighted which is a constraint at the moment is policy and regulatory uncertainty,” he said.

It is very difficult to know what the cost of doing business in South Africa is because of uncertainty over the Mining Charter, among other things, he said. “It’s very difficult to make long-term investment decisions while that uncertainty persists.”

Lonmin’s share price has taken a beating in recent months, sliding from more than R44 a year ago to about R19.40. Its market cap has shrunk to about R6-billion.

The environment that Lonmin and other mines operate in cannot be ignored. Besides concerns about the demand for commodities and over China’s growth, local mines face a host of local problems, including regulatory uncertainty because of delays in finalising the Mining Charter and proposed amendments to the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act.

This is exacerbated by tensions between the industry and the department of mineral resources over the disproportionate enforcement of regulations, for example, the implementation of mine stoppages under section 54 of the Mine Health and Safety Act. Stoppages are estimated to have cost the industry R4.5-billion in 2015.

Last year, companies such as AngloGold challenged the department in court over the inappropriate use of section 54 stoppages and won.

Lonmin’s majority union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, has also raised concerns about the broader political climate affecting the company.

The union held a meeting with members in February at which productivity and absenteeism were addressed, said Amcu treasurer Jimmy Gama, and these have improved.

A major challenge is “instability in terms of how the government runs the administration”, Gama said. “When investors have no certainty over how the country runs, it has the potential to affect our resources as well.”

The recent Cabinet reshuffle, and the appointment of a new finance minister in particular, whose ability to run the department is unknown, affects the economy and the currency, which has serious implications for commodities, he said.

Despite concerns, Lonmin’s worth is viewed as greatly undervalued. Nedbank Corporate Investment Banking, in a research note released in February, said Lonmin has “within its assets and its people the ability to change the story — from survival to a real investable future. Do another equity issue, do it now and do it with conviction,” it added in the note.

The company’s smelting and refinery assets were worth more than its market cap at the time but additional money “could turn the base into a story of low-cost production that can expand, even in bad times”.

Concerns over Lonmin’s liquidity may be overplayed, according to recent research note by UBS. It estimates the company has sufficient cash for the next 36 months, unless the platinum price drops further or its lenders withdraw their facilities.

The PIC said it hasn’t been approached to participate in another rights issue and doesn’t want to speculate about what its reaction would be if it was asked. It emphasised that its investment decisions are guided by its client investment mandates and are done for their benefit.