Shell shock: Since 18 Norman Street was attacked and burnt by infuriated Rosettenville residents

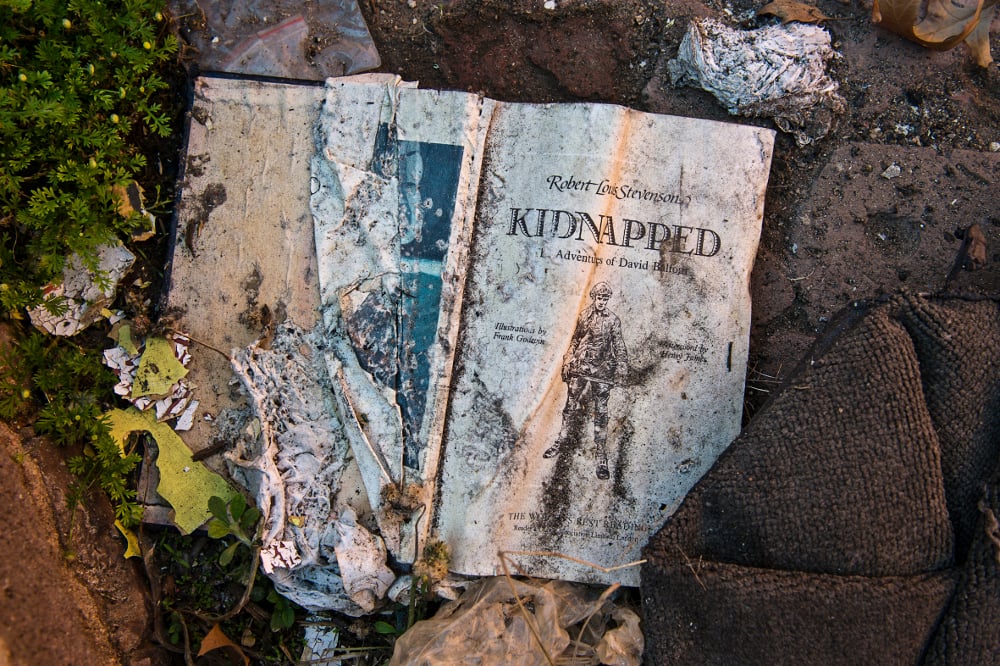

A well-thumbed novel lies open on the floor, centimetres away from used condoms and empty plastic bankies, with traces of a white powder still inside them. The book is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped; it begins with a journey to a ruinous place of fear and evil.

The book and other discarded items lie in a place that was once a home. That was before the spaza shop. Before the sex workers and their pimps moved in. Before the anger of the residents spilled over into a blaze. Before even the nyaope addicts. This is 18 Norman Street in Rosettenville, Johannesburg. This is the story of a house.

Quiet neighbourhood

At 18 Norman Street, a father opened his gate on a Sunday morning dressed in his shirt, tie and polished shoes. The squeals and excited banter of his young children carried from the backyard. In early 2013, the corner of Victoria and Norman streets was quiet. Neighbours knew each other by name. They looked out for each other.

The area was dominated by elderly people, says a 64-year-old neighbour to Number 18.

Now, his house is surrounded by reinforced palisade and electric fencing, the perimeter monitored by closed-circuit cameras. “The Nigerians” lingers on fearful lips like a bogeyman. The neighbour refuses to reveal his name for fear of reprisals.

Rosettenville residents talk of “the Nigerians” as the ringleaders of the drug and sex worker rings that have mushroomed in the suburb — whether they are Nigerians could not be verified by the Mail & Guardian.

The people who moved in after the family left the house were all young men. It didn’t take residents long to realise they were now living near a brothel.

When the neighbour emerged from behind his security cordon, the taunts started: “Get out! Get out!” or “You better sell your house!”

The pavement outside his house became a no-go zone after nightfall. In his letterbox, he routinely found threatening notes demanding he sell his house.

“I have picked up condoms and tissue paper from people having sex against my fence at night. It’s happened so many times. I can’t even walk the streets anymore,” he said at his gate, appearing eager to return to the safety of his yard, behind his 2.5m reinforced steel gate.

At 18 Norman Street, the yard is littered with condoms — there are dozens, used and unused — empty alcohol bottles and items of women’s clothing.

The neighbour carries pepper spray at all times and asked his brother to move in with him. Every trip out of his home is accompanied by a thorough security check.

Another neighbour, a 20-year-old woman, said “everything changed when the Nigerians came three years ago”. Her father raised their wall soon after their arrival, only to have their house burgled anyway.

Now, a sense of fear dominates her attitude towards the neighbourhood. “My mom is terrified to walk out the front door. They deliberately target the school kids. They look for the uniforms, give them nyaope and get them hooked. They give them freebies and demand payment later,” she said. “A friend of mine got involved with them. When she didn’t pay up, they cut her face,” she said.

Tuck shop

Kadir Kasem (46) opened his general dealer “Saad tuck shop” in the garage of 18 Norman Street in August 2015, selling bread, milk and nonperishable food, fresh vegetables, cleaning products, cigarettes and airtime. He named the shop after his son and got one of his Ethiopian countrymen to live in the room adjacent to it, in the corner home’s yard.

For six months business continued smoothly. Kasem paid R3 000 rent to a man who had already occupied the house. He never asked who he was or whether he owned the house. While delivering stock every week, Kasem said he received no reports of “crimes” happening in the house.

Kasem hired locals to paint advertisements of items for sale on the outside walls soon after it opened: rice, washing powder, sunflower oil, brown sugar and maize meal.

Two years later, these painted adverts are the only signs of a time when the house did not stir up controversy or hatred among its neighbours.

“Everything went fine when I opened, business was very good,” Kasem said this week. “The street was quiet. Mothers and children came to the shop all the time to buy sweets. Children played in front of the shop.”

But, by December 2016, residents of Rosettenville had grown impatient with law enforcement’s inaction about their complaints over brothels and drug dens, and Kasem had noticed a marked increase in the number of men loitering at street crossings.

“There used to be many people standing on corners and women coming to cars,” he said. “I wanted to close it that time but people were still buying from the shop.”

The dealers who lived in the house had an established system, known to their customers, to sell the drugs.

“One of the guys would stand at the bottom of the road and, when you pass there with the car, you give him the money,” said one Rosettenville resident. “At the top, here at the corner where the house is, there will be another Nigerian guy with big muscles waiting. He gives you the drugs, then you drive off.”

Two months later, in February, 18 Norman Street was one of the Rosettenville residents’ first targets in fighting the drug scourge. Frustration erupted into vigilante justice. The house was attacked with petrol bombs and the furniture carried outside and torched on the pavement. Kasem’s shop was looted.

“They took everything, everything. They didn’t even leave one packet of food or soap. Only shelves [were left],” he said. He lost nearly R25 000 to looting that day.

When the M&G visited the house the day after the attack, five men were cleaning up and repairing the electrical box in Kasem’s shop.

Sex and drugs

Residents of Victoria and Norman streets this week said for years they suspected the house was occupied by sex workers and their pimps. But it was the sale of drugs that started six months after Kasem opened his shop that confirmed their suspicions and turned the corner into a vibrant market for the sale and consumption of illegal substances.

“Once they started selling drugs, it made it easy for the addicts, because the girls were also addicted,” said Caldrin Johnson (20), who is unemployed and hangs around the neighbourhood. “Because they would go inside to smoke and stay there with the girls until they were done, so it was convenient.”

From residents’ accounts, things escalated visibly. The sex workers started advertising themselves to passing motorists without fear.

This was not the only drug den and brothel in the suburb. Their proliferation was so apparent that it ignited the Rosettenville’s residents to take action.

Johnson said the brazen attitudes of drug dealers and sex workers astounded him. “Every single night, 10 to 15 girls stand out on the corner. Cars come up, park for a minute and then drive away. Everyone knows what’s going on.”

He said there were attempts to rescue the women staying in the brothel. He recalled walking up the road and passing the house with his mother, when they spotted one of the women standing outside. “My mom did try to help them and told her, ‘You don’t have to do these things,’ but the girl just laughed,” Johnson said. “I told her [mom] the [women] stay here because they get the drugs for free and [they] like the money.”

Kasem has now moved his spaza shop to a new location further up Norman Street. Another resident, while helping the grocer offload fruit and vegetables, said, when the sale of drugs started, most of the neighbours stopped leaving their homes at night.

“We were instantly afraid because now it wasn’t just girls, it was these big guys on each corner as well. I couldn’t go out at night anymore, I would get robbed,” the man said.

He, too, is afraid to give his name, claiming the dealers take note of who speaks to the journalists who have visited Rosettenville since the residents started protesting against the drug dens and brothels.

Nyaope boys

The electrical box and shelves left by the residents in the looting spree were found and stripped from the walls by the “nyaope boys”, as they’re called by Johnson and his friend, Simphiwe Tsele, a 22-year-old who is also unemployed.

“It’s their house now. They have taken it for smoking drugs and stripping anything left inside. The people that buy [sex] also use the house,” Johnson said.

“They stay here because it looks abandoned. At night they can do whatever they want and people won’t think anything’s happening because it’s dark,” Tsele added.

The most prized possession stolen by the nyaope boys after residents launched the arson attack was the 4m-wide steel gate, Johnson said. “They stole that before anything else.”

The metal meant a big payday for scrap dealers.

Any item of plausible value was looted; the pipes and wiring were taken in the days and weeks following the attack on the house. Below the front porch, the home’s earth cable has also been dug out and stripped for its copper, a valuable metal that earns R50 a kilogram at scrap dealers. The handle on the back door and its hinges are the only metal items left in the house.

Between February and June, the presence of people smoking drugs in the burnt-out building merged with brothel activity. Used and new government-branded Max condoms lie next to the plastic used to package nyaope inside the room that Kasem’s employee once called home.

The room’s window was boarded up after its glass was broken and the frames were stolen. An old mattress and dirty sheets fill the floor space in what Johnson called the “fuck room”.

A narrow alley separating the property’s exterior wall from its garage and outbuilding is littered with rubbish and fresh human faeces.

A blooming pink rose bush grows in the corner of the front yard, staring down at the broken windows and walls of what was once a home.