The agricultural sector must ensure food security, create employment and contribute to GDP growth.

COMMENT

Ratings agency Moody’s recently downgraded South Africa’s top five commercial banks, along with the Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa and the Land Bank, to one notch above sub-investment grade.

Moody’s said the primary reason was weakening credit and the lowered macro profile of the government. This puts pressure on banks in a difficult operating environment characterised by a pronounced economic slowdown.

It follows a decision by Moody’s to downgrade South Africa’s sovereign rating as a result of three key drivers:

- Weakening institutional frameworks;

- Reduced growth prospects reflecting policy uncertainty and slow progress with structural reforms; and

- The continued erosion of fiscal strength owing to rising public debt and contingent liabilities.

This confirms that policy uncertainty and the lack of strong economic and political leadership, which has triggered the unstable political environment, are posing a threat to the economy.

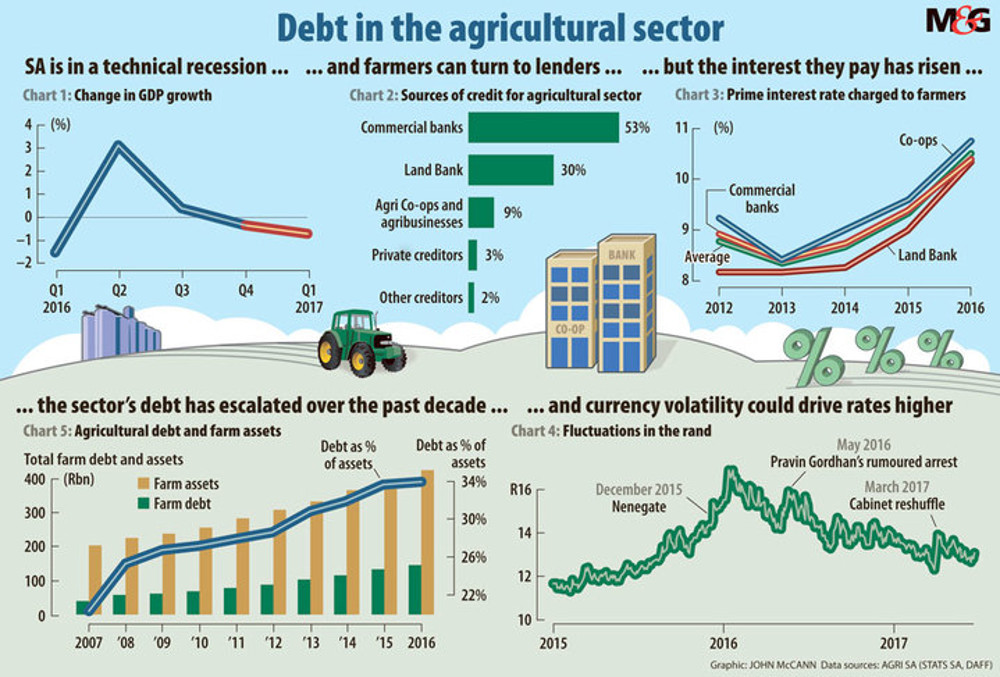

Moreover, uncertainty over policy priorities has damaged investor confidence, reducing investment in the country’s economy, which is already in a technical recession after two straight quarters of negative growth.

The bank credit rating downgrades will invariably lead to a higher prime interest rate and ultimately higher cost of credit. This means it will now be more expensive for banks to borrow money and that may be passed on to consumers in the form of higher interest rates and bank fees. This will have a huge knock-on effect on the ways consumers and businesses can access credit.

Although it is still too early to tell exactly how the markets will respond to the bank downgrade, high levels of debt in the country and by the country (government in particular), in addition to the previously mentioned issues, are creating risk for the economy, something that hasn’t escaped notice beyond our borders.

Given that farmers rely on financing from commercial banks and the Land Bank, the credit downgrading of these banks will have an adverse effect on the recovery of the sector, particularly from the recent drought that saw the productivity and profitability of farmers and agribusinesses come under enormous pressure in recent production cycles.

Commercial banks and the Land Bank are the largest financiers in this sector. As sources of credit for farmers, they constitute 53% and 30% respectively. Agricultural co-operatives constitute 9%.

Importantly, the prime interest rate these financiers charge has been rising since 2014, after falling to an average of 8.35% in 2013. In 2016, commercial banks, agricultural co-operatives and the Land Bank charged an average 10.5% and this is likely to increase because of the bank credit downgrading.

The Reserve Bank’s previous Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meetings signalled an interest rate cut amid significant easing of inflation. But, given the current economic turmoil, the MPC has reconsidered and concluded that it would be too risky to cut rates at this stage.

In addition, given South Africa’s increasing international volatility as a result of the credit downgrading, the Reserve Bank has to practise a greater level of caution in how it adjusts interest rates.

It is not unique to South Africa that, despite declining inflation, a central bank decides to hike interest rates. The United States Federal Reserve recently approved yet another interest rate hike for 2017 amid expectations that inflation was running well below the central bank’s target. This was its second interest rate hike this year after an increase in March. Policymakers project that there could be one more hike this year in the US.

Usually, when the Federal Reserve hikes interest rates, it is an indication of how other central banks around the world will adjust theirs, especially in emerging markets such as South Africa. But the reasons behind the adjustments may differ significantly.

Sometimes when an economy is growing at a rate that is said to be too fast, a central bank may respond by raising interest rates to curb spending and encourage savings.

Another reason that may force a central bank to increase interest rates relates to local currency fluctuations in the global market, usually because of domestic factors such as commodity prices and other economic variables, the political environment, policy uncertainties, social unrest and other international factors. Domestic factors, particularly an unstable political environment, have a significant effect on how a local currency performs in relation to others in the market.

For example, since President Jacob Zuma fired Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister in December 2015, the rand has struggled to get below the $12 mark. The decision landed South Africa in the biggest financial crisis it has experienced since the advent of democracy.

We witnessed the same trend when there were rumours that former finance minister Pravin Gordhan would be arrested and when Zuma reshuffled his Cabinet.

Although a weaker rand might benefit exports, it leads to an increase in the cost of imported agricultural inputs, particularly chemicals, fertiliser and fuel. Also, given that domestic grain prices are derived from international prices, a sustained weak rand fuels consumer inflation, thereby eroding purchasing power. When this happens, the Reserve Bank may be forced to delay interest rate cuts or even increase them.

During the MPC meetings in late May, the Reserve Bank decided to keep rates at 7%. This is highly unlikely to happen at the next MPC meeting, which is scheduled for July 18 to 20.

It has already been noted that the agricultural sector has shown strong resilience and contributed positively to gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of 2017, despite poor production output in the Western Cape. The contribution was driven primarily by forestry and horticultural products, particularly fruit exports. In addition, the sector’s outlook for the current season is showing positive signs, being driven by a robust recovery in agricultural production, particularly that of summer grains and oilseeds.

I have recommended previously that agricultural development be made a national priority as it is an area of growth and plays a crucial role in the broader economy. On the employment side alone, agriculture constitutes about 5% of the country’s labour force. This is double the contribution by mining and almost on par with the transport sector.

Although those in the agricultural sector celebrate its recovery from the recent drought and the contribution it has made to GDP in recent times, the increased cost of borrowing as a result of credit rating downgrades will have a huge effect on the ability of farmers to access and repay credit.

Over the past nine to 10 years, the agricultural sector’s debt has risen exponentially and it is expected to worsen as a result of the bank credit downgrade. The sector’s debt increased by 9% on the year in 2016 to more than R144-billion.

The downgrade implies that banks will revise their pricing model for individuals and businesses, including farming. Consequently, this will further increase farmers’ debt and ultimately weaken their financial positions and probably delay or reduce investment in the sector.

The bank downgrade could also result in reduced employment in the sector. It is important to note that farming operates differently to other businesses.

Farmers usually don’t have funds readily available for day-to-day operating expenses. They must first cultivate the soil, plant the crop, let it grow, harvest it and sell it — only then do farmers get their income. Before that, they rely on banks to finance their running costs, of which salaries make up a large component. At a significantly higher interest rate, farmers might not be able to afford the same lines of credit and this will have an adverse impact on the day-to-day operations of a farm.

The biggest concern regarding the bank downgrade is that it will probably reverse the recovery of the sector for the next production cycle. The agricultural sector has a fundamental responsibility in the economy. It must ensure national food security, as well as contribute towards employment creation and GDP growth. But none of this can happen unless the sector is allowed the space in which to operate effectively and profitably.

Ultimately, the problems South Africa is facing, be it the downgrade, lower investment confidence, high levels of unemployment or slow economic growth, are all self-inflicted.

Ministers tasked with ensuring the country prospers are instead making irresponsible pronouncements on issues that do not fall in their ministry, such as: “Let the rand fall, we will catch it.” Such statements are damaging to the economy.

Then we have people heading our chapter nine institutions, such as the public protector, interfering in issues outside of their mandate and neglecting their call of duty to investigate acts of corruption, which is sending South Africa into a downward spiral.

All these issues are having a significantly negative effect on the country’s ability to grow, and other countries are taking note. Much more needs to be done, and swiftly, to restore stability and investor confidence.

Hamlet Hlomendlini is chief economist for Agri SA. This is an edited version of an Agri SA article