The accumulation of capital and technology has changed how wealth and power are articulated to land.

For most of human history, land — a share of the Earth — has been the material ground for domination and freedom. Land has enabled wealth, power and the sense of meaning that comes with being able to dwell and live in a particular place.

Capitalism, a phenomenon that was and remains fundamentally raced, was initially made possible by the commodification of land, through violent dispossession, and of people, through enslavement.

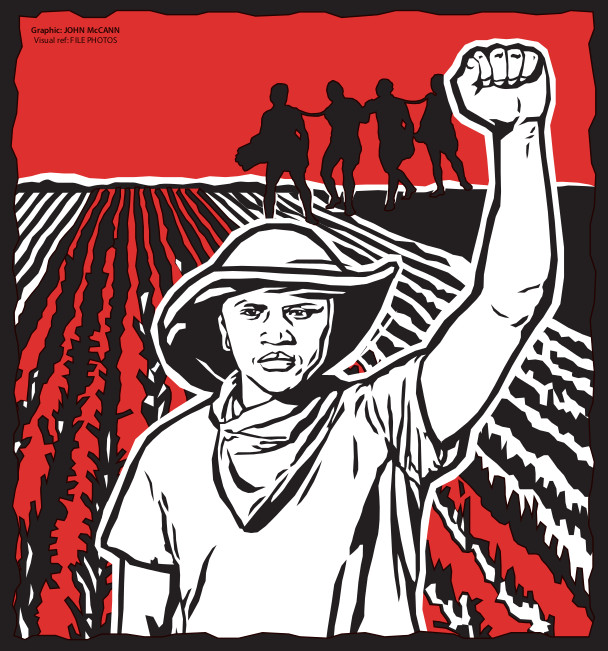

But there have always been counter-modernities, frequently read as monstrous from above, that have refused the incorporation of the Earth itself into the racial order and posed the social value of land against its commercial value.

During the English Civil War the Levellers, wearing sprigs of rosemary and sea-green ribbons, sought equality before the law. The True Levellers, or the Diggers, were less enamoured of what Aimé Césaire would later call “abstract rights” and sought ownership of the land in common.

In April 1649, Gerrard Winstanley led a group of Diggers in a land occupation on St George’s Hill in Surrey, in protest at the “cursed bondage of inclosure” and proclaimed the Earth as “a common treasury for all”.

Forty years later, John Locke, the English liberal philosopher, writing in defence of private property, presented the commons, in England and in the New World, as “waste” — waste to be redeemed and turned to profit by enclosure: a process that would be fundamentally raced in Ireland and the New World.

Locke’s logic remains hegemonic. St George’s Hill is now a gated community for the super-rich, with tennis courts and the inevitable golf course.

But Locke was not only a partisan of private ownership, and profit, against the commons. He was also a key figure in the development of the liberal political order in which the count of the human was mediated by the fabrication of race.

The roots of this project are sometimes traced back to 1095, at the beginning of the Crusades, when Pope Urban II issued the papal bull Terra Nullius (Empty Lands). It gave Christian armies the right to appropriate lands occupied by people who were not Christians.

But by the 17th century, when Locke was writing, religion was giving way to pseudoscience in the form of the idea of race as the means to regulate the count of the human, and the right to land. In The Tempest, first performed in 1611, Shakespeare has Caliban declare to Prospero: “This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother, which thou takest from me.” The language might be somewhat archaic but the sentiment remains entirely contemporary.

When modern forms of domination have been constituted through a hold over land, resistance has often been a matter of flight, of moving from one part of the Earth to another.

The mountain, the forest, the desert, the lands beyond the reach of oppressive authority and, in the great age of piracy, the ocean, have become sites of freedom and sites from which to strike at oppression.

Those who have come to hold land through conquest and enclosure have confronted all kinds of refusal of their authority, from quiet encroachment hidden by the performance of deference to furtive forms of commoning, sabotage and open revolt.

The most fundamental of the three revolutions that made the modern world was the revolution against enslavement that resulted in the independence of Haiti in 1804. The people who made the revolution held profoundly contradictory ideas about their relationship to the land.

In a letter written in 1797, Toussaint Louverture, at the time the leader of the revolutionary armies, declared that after the revolution a return to the plantations was “the only thing that may give Saint-Domingue back its old splendour”.

But there was a mass refusal of the idea that freedom would require former slaves to return to the plantations as wage labourers. Against this, people chose the far more egalitarian option of autonomous small-scale agriculture.

Every successful anti-colonial movement since then has, at some point, had to confront the fact that while all colonised people may share an interest in opposing colonialism, there are very different material and political interests at stake in terms of what comes next.

The will to deny this in the form of the affirmation of some kind of permanent unanimity invariably functions to mask the particular interests of elites in the guise of the general interest.

The accumulation of capital and technology has changed the ways in which wealth and power are articulated to land. But the land question sustains a contemporary urgency. In each of the revolutions that convulsed Mexico, Russia and Spain in the first decades of the last century, the banner of “land and freedom” was unfurled. The Kenya Land and Freedom Army organised the insurgency that shook British colonialism in the 1950s.

In October 1958, the rebel army led by Fidel Castro in the mountains of southeast Cuba issued law number three of the Sierra Maestra. It declared that tenant farmers and sharecroppers were entitled to the land they worked.

In the early 1960s, peasants in Peru’s Cuzco Highlands built an effective movement that organised land occupations under the banner “land or death”. The phrase reached a global audience through Hugo Blanco’s book, written in prison, which took this slogan as its title.

In 1970 it was famously argued that part of the reason why the Americans were not able to win the war in Vietnam was that they had offered the peasants a constitution, whereas the Viet Cong offered them land.

Around the turn of the century the urban land occupation, and forms of organisation centred on bits of territory in the interstices of cities, were central to the mobilisations that opened new vistas in countries such as Bolivia, Haiti and Venezuela.

Today, land is at the heart of the largest popular movements in the world, the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil, the Naxalite insurgency in India and much of the conflict between impoverished people and states, as well as private power, in cities across the global South.

With the majority of humanity now living in cities, often without formal employment, the urban land occupation and the road blockade have become key mechanisms to enable participation in the common and disruption. The right to the city, a right to shape the city as well as to a presence in the city, is now entwined with the struggle for land.

In South Africa, commercial farming, including game farming, and mining, continue to drive rural dispossession. These processes are often acutely raced but are also tied to international capital and, particularly in the case of mining, often mediated through traditional authority and local elites.

Our cities have simultaneously become sites of sustained conflict between impoverished people and both private power and the local state. Abahlali baseMjondolo, the largest and most effectively sustained popular movement outside of trade unions and political parties, lists its primary concerns as land, housing and dignity.

Since attaining state power, the ANC has never been able to marshal the political will to use the instruments available to it to address the land question in the countryside or the cities.

In the countryside, its interventions consistently lean towards the interests of elites and traditional authority. In the cities, much of its developmental agenda has taken a neo-apartheid rather than a democratic form, aiming to warehouse impoverished black people out on the urban periphery.

People who have resisted ongoing dispossession or organised new land occupations face serious repression. They have been placed outside of the law and subjected to extraordinary slander and routine brutality extending to torture and murder.

In a noxious ideological move, the ANC’s failure to address the land question has frequently been misrepresented as consequent to the Constitution and popular struggles as consequent to white or foreign plots. This enables the authoritarian currents in and around the party to misuse the party’s own failures, and popular responses to those failures, to drive an authoritarian agenda.

At the same time, significant actors in and around the party are seeking to renew its legitimacy by escalating a combative discourse on land.

It is not impossible that, as the President Jacob Zuma faction or the party as a whole confront the real possibility of defeat, this discourse will be translated into some sort of action. But there is a fundamental difference between raising injustice to seek to address it and raising injustice to misuse it to legitimate a new injustice.

If the ANC does seek to renew its legitimacy by taking real action on the land question, it seems highly likely that it will do so in an authoritarian manner that strengthens its repressive capacities and primarily benefits people in and around the party through an expansion of the patronage machine.

There is very little chance that land will be allocated on the basis of a democratic and social logic.

The Zuma faction in the ANC is undeniably predatory, authoritarian and repressive. It, its various groups of armed men and its tin-pot demagogues appropriately attired in black shirts need to be opposed, firmly and directly, at every turn.

At the same time ongoing struggles, rural and urban, for bits of the Earth, require committed support.

Richard Pithouse is the senior researcher at the unit for the humanities at Rhodes University, and a visiting researcher at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research