The tenants on Ria Nonyana-Mokabane's family land have been without electricity

COMMENT

Many proposals about land reform are being thrown around ahead of the ruling party’s elective conference in December.

Not only have I worked in land reform, housing and local government as a lawyer, we are also a black family that owns a piece land.

It has, over time, grown to become a conundrum and a headache for the family. It is 85 hectares of land, in Moutse, under the Elias Motsoaledi municipality, in Limpopo. The land was first purchased by our grandfather many decades ago during apartheid times and later passed on to our father after he bought out his brothers and sisters.

Our family has lived there for two generations. The land has a private family burial site, a residential property and business premises. Our immediate family now lives in Motetema township, some 50km away from the land, but a few family members still reside on the land.

During apartheid times our family decided to allow several families to settle on the land as tenants for a minimal annual rental fee paid to our family. There was demand for land then, because of the inhumane policies of the past. Families were allocated stands and allowed to erect permanent structures on our private property.

In the post-apartheid era, our father decided to sell the land to the government because it had become difficult to manage the tenants and collect rent, owing to unlawful occupation.

The lawful and unlawful occupants could not have quality lives on the land because of the lack of access to service infrastructure such as water, electricity and RDP houses because the property was privately owned.

Our family approached the provincial and municipal governments in the mid-1990s with an offer to sell the property to the community. Our father died a few years later still waiting for a response.

Ownership of the property passed to our mother.

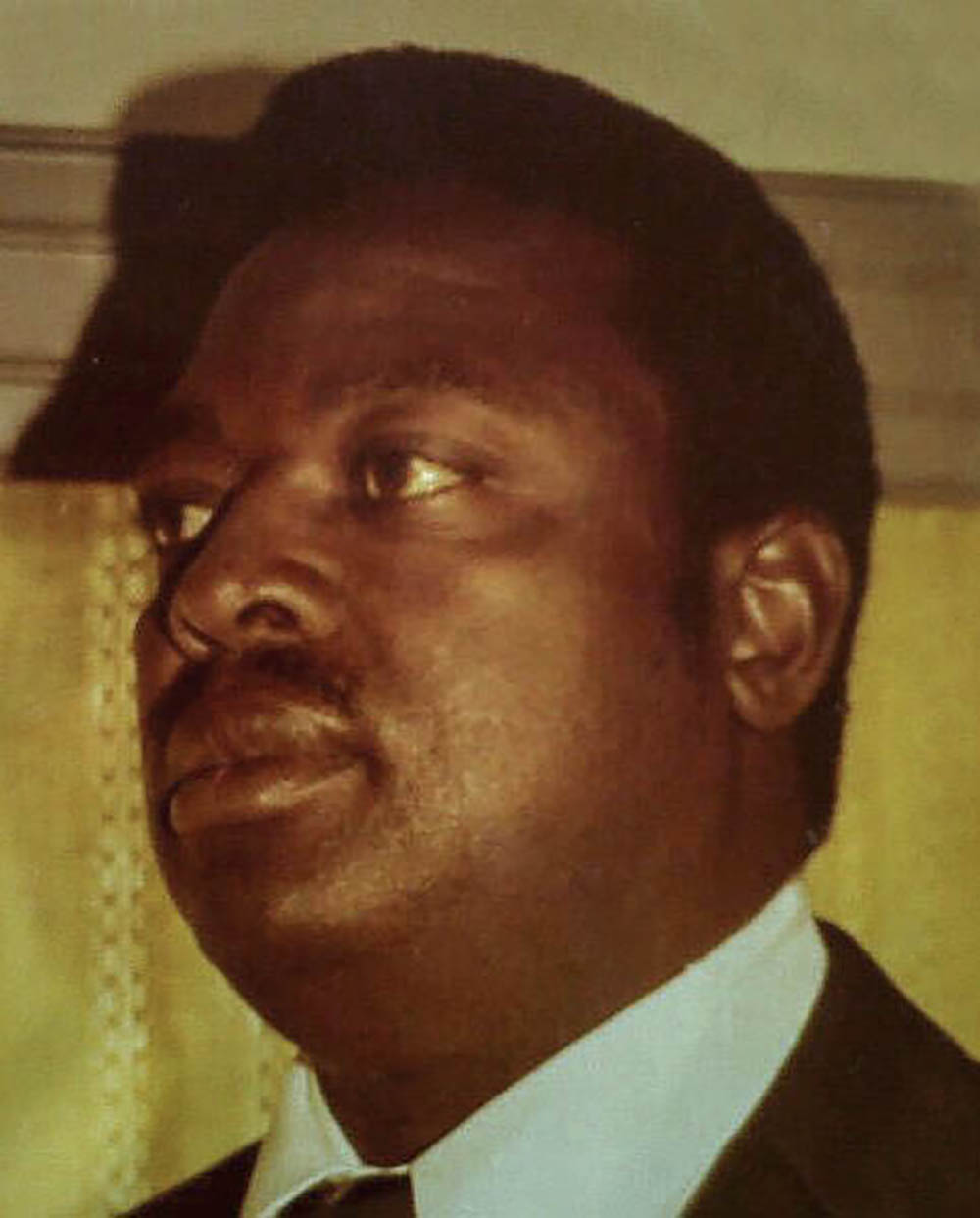

The late Schoeman Choeu Nonyana. (courtesy Ria Nonyana-Mokabane)

There are many reasons that have contributed to the long delay in finalising the sale. First, the area was many years ago part of a cross-border municipality between Limpopo and Mpumalanga. We had to deal with a municipality that is based in Limpopo and a provincial department based in Mpumalanga.

The cross-border issue was only resolved about a decade ago but this did not assist our case. Second, our case falls under land redistribution, thus we had to liaise with the national department of rural development and land affairs as well as with the municipality and the provincial department of housing on the other.

Grants to purchase land for residential settlement are managed by the provincial department working in partnership with the local municipality. We have also held discussions with the Housing Development Agency, government officials and the mayor, as well as the MEC and the provincial premier. Nothing was achieved by any of the discussions.

Third, in rural municipalities, the demand for land for housing is more acute in nodal areas with easy access to markets. Our land is strategically located to such a nodal area, as well as to a hospital, a police station, a taxi rank, a shopping complex and other social amenities. It is also next to a major public road. Despite all these advantages, our land offer has not received attention from the different spheres of government.

The tenants on our land have now organised themselves and have been lobbying the local municipality to prioritise their plight. Twenty-three years after freedom they are still without electricity, water and RDP houses because of the delay in purchasing the land from our family for the tenants.

As I write this article, we are still waiting on the government to respond to our offer. The wait has been long and with lots of frustrations. Our lives have been held hostage for many years now despite the talks we have had with government to conclude this transaction and with the tenants about the numerous promises made by government.

Activists and technocrats have been arguing that the “willing seller, willing buyer” lobbying principle is the biggest hindrance to meaningful land reform. In our case, we have been willing sellers for the past two decades and are still waiting for the “willing buyers” to come to party.

Our family headache continues and the tenants wait in the hope that some day “service delivery” will come to their part of the country.

Dr Ria Nonyana-Mokabane is a lawyer who has been involved in land reform, housing and local government, doing research, training and policy and legal work. The views expressed here are her own.