NEWS ANALYSIS

‘Failure is not an option.” These were the final words of Eskom interim board chair Zethembe Khoza’s opening address at the power utility’s financial results briefing this week.

But an 83% drop in profits, R3-billion in spending that flouted the rules of the Public Finance Management Act, spiking debt financing costs that are set to worsen, and a blistering array of allegations of corporate governance violations are arguably the embodiment of failure. And investors are watching — including the likes of development finance institutions such as the World Bank.

Despite an increase in revenue of 8%, the company’s profits slumped from more than R5-billion last year to R888-million — or by 83%.

“This tells you its expenses are out of control by miles,” said Iraj Abedian, chief executive of Pan-African Investment and Research Services. This was at the heart of the problems at the utility, said Abedian.

Although the company made a 2% saving on its biggest cost driver — primary energy, which includes coal and diesel purchases — other costs continued to creep up.

These included a 13% increase in its staff costs, a 26% increase in other operating expenses such as consultants’ fees and impairments for rising municipal debt, and a leap in its interest bill by 82% to R14-billion.

The state, however, will not let this ship sink — although the messaging from Eskom and the treasury over whether the utility may, in fact, need aid from the government has been contradictory.

In response to whether it deemed Eskom “too big to fail”, the treasury said: “Government will implement all the necessary measures to ensure that the entity remains financially viable and ultimately that it operates on the strength of its own balance sheet.”

The treasury declined to elaborate on what these measures would entail, specifically what “soft support” for the utility would involve. Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba used that term in his recently announced 14-point plan aimed at righting the sick economy.

The treasury said instead that the details of the “soft support” have not yet been developed but that “Eskom is responsible for developing the business case and [submitting] it to government for consideration”.

But at its results briefing, chief financial officer Anoj Singh, new acting chief executive Johnny Dladla and Khoza denied the company was in financial distress. “The answer is an emphatic no,” said Dladla.

Singh and Dladla were at pains to point out improvements in the company’s performance, such as the overall declines in primary energy costs and increases in cash generated from operations.

Debt hangover

Nevertheless, Eskom is facing some serious headaches on a number of fronts.

It still has to manage its cash flow carefully and analysts have been watching its liquidity buffer, or the money it needs to cover an average of three months’ organisational cash flow requirements.

It targets around R20-billion at a bare minimum. But cash and cash equivalents have slid to just above this, at R20.4-billion, down from R26.5-billion last year.

This was “due to increased capex [capital expenditure] spending coupled with increased interest payments”, Eskom said in its report.

However, the company said that with the incorporation of liquid assets, including investments in securities, the buffer was at a more comfortable level of R32.5‑billion. This is down, however, from R38.7‑billion last year.

The debt that Eskom has racked up in recent years to fund its expensive, and very delayed, capital expansion programme — covering the Ingula, Medupi and Kusile power stations — continues to weigh on the company.

Net finance costs rose from R8-billion in 2016 to R14-billion this year, or 82%.

This is excluding the R18.2-billion in capitalised finance costs for work that is still under construction, but that under international account practice will not yet show up in Eskom’s income statement until these assets come on stream.

This suggests there’s more pain in store for Eskom as more of the long-delayed units of Kusile and Medupi come online in the next two years.

An analyst told the Mail & Guardian that a better reflection of the money Eskom was actually forking out in finance costs could be seen in its cash flow statement. Here, financing costs paid for the year were about R28.8-billion.

Singh, however, gave assurances that these capitalised finance costs were included when Eskom calculated its cash interest coverage ratio. This is an indicator of the cash a company has on hand to cover its interest bill and, according to Eskom, it has exceeded the targets it set itself.

Perhaps the most telling extent of this problem is how dependent Eskom is on accessing debt to stay afloat.

“It is common cause that we are in a net borrowing position and our ability to continue as a going concern is premised on the basis that we have continuing access to debt capital markets,” Singh said.

“If something catastrophic had to happen tomorrow that limits our access to debt capital markets, which we are not aware of currently, then we would have to approach treasury [for financial support].”

Eskom must borrow just under R340-billion in the coming five years — starting with R71.7-billion in the current financial year. As of March, it had raised 53% of the required amount for 2017/2018, but this included bank facilities (of R6.5‑billion), putting the amount of committed funding closer to 45%.

The World Bank is watching

Eskom must raise this money under a cloud of allegations of corruption and corporate governance failures, as ratings agencies ponder whether once again to downgrade the country’s credit rating — a key determinant of the rate at which the country, and all those living in it, can borrow money.

In this environment — and after a spate of corruption allegations at a number of other state-owned entities linked to the Gupta family and President Jacob Zuma’s family — investor appetite for parastatal debt is drying up.

International development finance institutions are also concerned.

Responding to the M&G, the World Bank — which has lent Eskom about $4-billion — said it takes “allegations of corruption very seriously”.

“We have requested further information from Eskom and are awaiting a response and we will discuss next steps,” a spokesperson for the bank said.

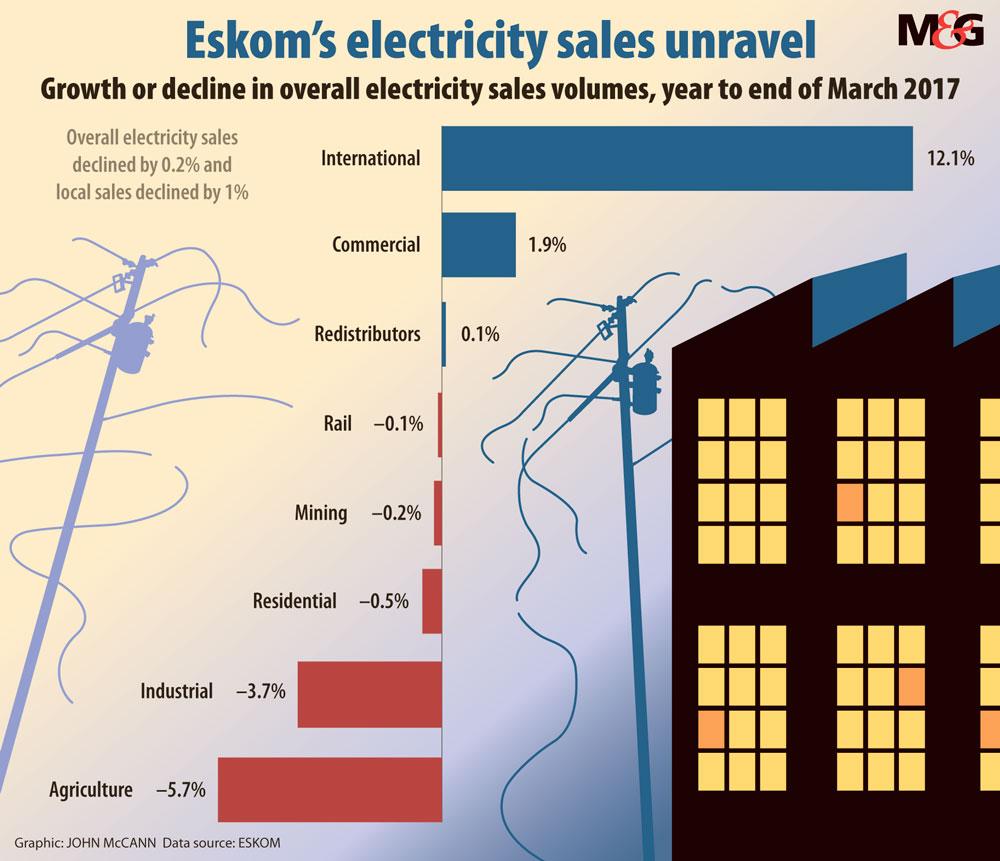

At the same time, Eskom is faced with declining demand for its electricity — even as the company brings more capacity online with the commissioning of more power from Medupi and Kusile.

In response to follow-up questions, Eskom said that it did expect some of its key ratios to weaken in the coming years as it continues to borrow to complete the build programme, and less interest could be capitalised as the expansion programme comes to an end.

These ratios would strengthen again after the capex programme ended. But cash from operations was expected to “increase substantially” over the next three to four years, the power utility said.

As demand has slumped, Eskom has propped up its sales by selling more electricity to neighbouring countries.

The company said it aimed to grow export sales in the coming years. To stimulate local demand, it was in the process of contacting customers that had shelved large projects, to encourage them to “revisit” those plans. It was also in consultation with customers that had cut down operations “to investigate the possibility of them increasing sales”.

The company said that staff costs were in line with agreements made with labour unions but it expected that manpower numbers would be reduced over the next five years.

Other contributors to rising costs included the losses experienced after Eskom had to increase provisions for bad municipal debt — which rose from R6-billion to R9.6‑billion. Another cost driver was mine-related environmental provisions. If these provisions were excluded, other operating costs would only have risen in line with inflation, it said.

At the results announcement, the executives admitted that Gupta-linked consultancy Trillian had received R495-million in fees, on top of the R900-million paid by Eskom to McKinsey.

Eskom did not clarify whether these payments made up the bulk of “managerial, technical and other fees” that chewed up R1.4-billion from its bottom line. It only said that these fees are paid to “many other consultants, such as engineering, managerial and specialised consulting services”.

These problems notwithstanding, Eskom still believed bonuses for its executive teams were warranted and, despite its own auditors deeming as irregular a pension payout of R30‑million to former chief executive Brian Molefe, Eskom will defend its decision in court. But Abedian said, under these circumstances, bonuses should never have been countenanced.

Eskom’s presentation of its results amounted to “smoke and mirrors”, he said, and “takes the nation as fools”.