The National Prosecuting Authority announced that the Timol inquest would be re-opened after receiving material from the Timol family that had been collected in the years the family has taken to investigate his death.

At the Ahmed Timol inquest this week, it was like a rewind button had been pressed. It’s as though Timol’s body, which fell from the 10th floor of the then John Vorster Square in 1971, had stopped mid-fall, and soared upwards, back through the window and into the room from where it dropped.

In what was called Room 1026, there is a table and a chair. The apartheid police officer who sits on the chair is named Joao Rodrigues. He testified in 1972 that Timol suddenly jumped to his death after he asked to go to the bathroom.

It emerged this week that anti-apartheid activist Timol was in no condition to stand that day, let alone clamber up on to the ledge below the window in what is now known as Johannesburg central police station, and push his body through.

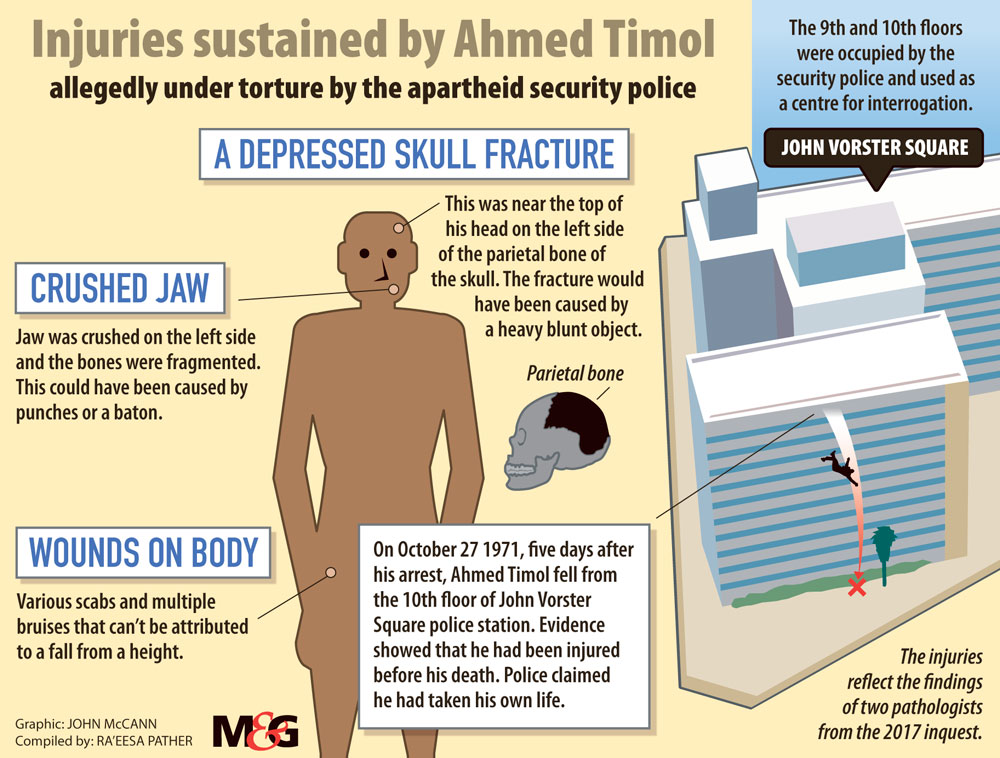

On Wednesday forensic pathologists told Judge Billy Mothle, who is presiding over the inquest, that the left side of Timol’s head was bashed with a heavy object that severely fractured his skull.

“There are a number of injuries that are not consistent with a fall from a height,” Dr Shakeera Holland said.

Holland and another forensic pathologist, Professor Steve Naidoo, pieced together the injuries Timol endured before his fall from a pathology report written by Dr Nicolaas Scheepers, the apartheid state pathologist who performed the autopsy on Timol’s body in 1971.

What they found was that before he fell, Timol was either unconscious, in a coma, or slipping in and out of consciousness. He was too weak to walk.

When his body thudded to the ground, the base of his skull fractured and his brain was damaged. He had seconds, maybe minutes, before he took his final breath.

What present and future generations will perhaps never know is the time at which Timol was injured before the fall. Scheepers’s report had valuable information missing, such as the colour of the bruises on Timol’s body and a measure of his wounds (their depth, width and length), which could help to estimate when he had been injured.

Timol, a member of the ANC and the South African Communist Party, had been detained for five days before he fell. The Timol family believes he was tortured.

Missing inquest pages

Also missing are the first 782 pages of the original inquest report into Timol’s death that are simply “not available”. Captain Benjamin Nel, a police officer with the Hawks, said in an affidavit submitted to the current inquest that efforts to find the pages had failed.

Then there are the missing pages of Dr Jonathan Gluckman’s review of Scheepers’s autopsy report. Gluckman was hired by the Timol family to be in the room with Scheepers as he performed the autopsy.

But Gluckman’s full report is nowhere to be found. Timol family attorney Moray Hathorn told the Mail & Guardian that when he contacted attorneys who were said to be safeguarding it, they did not have it.

These missing links, however, have not stopped expert witnesses from rewriting the wounds on the 29-year-old’s body and telling the story of a man in pain who suffered before he died.

Old enemies not yet reconciled

On Monday, the inquest heard of the torture methods used by the Security Branch. Paul Erasmus, a former fieldworker for the apartheid police, spoke freely about the torture he had seen during apartheid. With long grey hair, round glasses and a Security Branch notebook at his side, Erasmus graphically detailed the electric shocks and violent beatings he had witnessed. The methods were not new revelations, but the court was utterly still as he spoke.

His speciality was to spread “disinformation” – apartheid fake news – to discredit liberation movements. On Tuesday, former minister and SACP heavyweight Essop Pahad told the court that certain documents, allegedly circulated by the state to explain away the deaths in detention of SACP members, were forgeries. One document said the SACP encouraged its members to kill themselves if they were captured so that they would not reveal the names or locations of those in the SACP. Pahad refuted these claims.

“It was never part of SACP policy or ANC policy that anyone would be asked to commit suicide,” Pahad said.

His remarks were backed up by former SACP activist Stephanie Kemp, who had been captured and tortured in 1964 for suspected anti-apartheid activities.

The inquest has not just revived Timol’s last moments. It has also, in a small, nondescript courtroom, brought together old enemies. The court adjourned on Monday soon after Kemp testified, and Erasmus excitedly opened an old notebook in which he had scribbled down lecture notes from his Security Branch classes. On a page, he pointed out a name he had neatly written: “Stephanie Kemp”.

“It’s amazing,” he told the M&G. “I must go meet her.”

He bounded off in Kemp’s direction and shook her hand animatedly. The bizarre interaction continued as he opened his notebook for the flabbergasted Kemp, who smiled tightly and walked away after the encounter.

“They used to tell us she was a monster,” Erasmus said, referring to his Security Branch seniors.

It was a singular moment, one that 23 years of democracy had not yet managed to reconcile.

Quest for truth is paramount

References to scrapes, fractures and damaged organs were repeated often in court to describe Timol’s mangled body. But Mohammad Timol, Ahmed’s brother, gave a small laugh as he told the M&G: “Luckily I can’t hear so well.”

Imtiaz Cajee, Timol’s nephew, said that it is the truth that matters most. If Rodrigues is found to have lied in his original testimony, Cajee said the family would not pursue prosecution.

“We don’t want to see him go behind bars and find him culpable for lying. We want him to give us the true version of events. If he can tell us how it was done and how it was covered up, for us that’s everything,” Cajee told the M&G.

As Erasmus spoke of the commendation he received from the apartheid state, Mohammad Timol read a newspaper from 1977. On the front page was a headline story about Matthews Mabelane, who died in that year. He, too, according to apartheid police, fell to his death from the 10th floor of John Vorster Square.

The Mabelane family is one of 71 other families who lost loved ones in detention between 1963 and 1990. For them, the Timol inquest is a chance to reopen investigations into who was to blame for the deaths of family members who “fell down stairs” or “jumped out windows”.