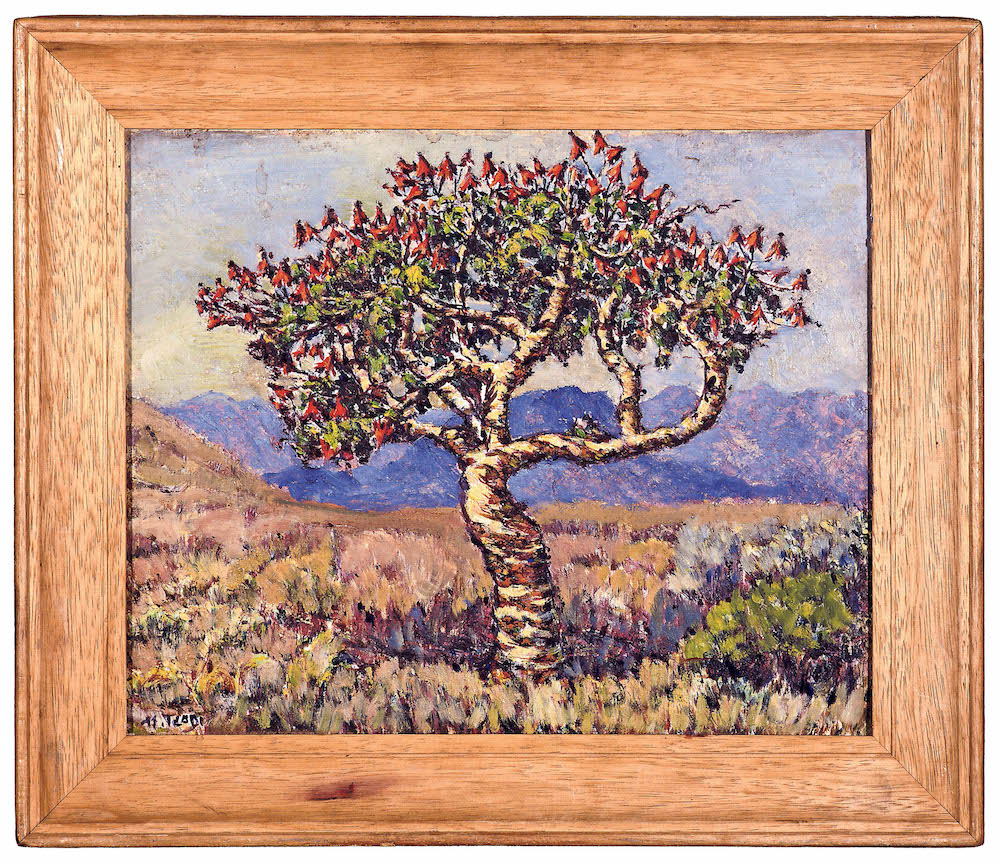

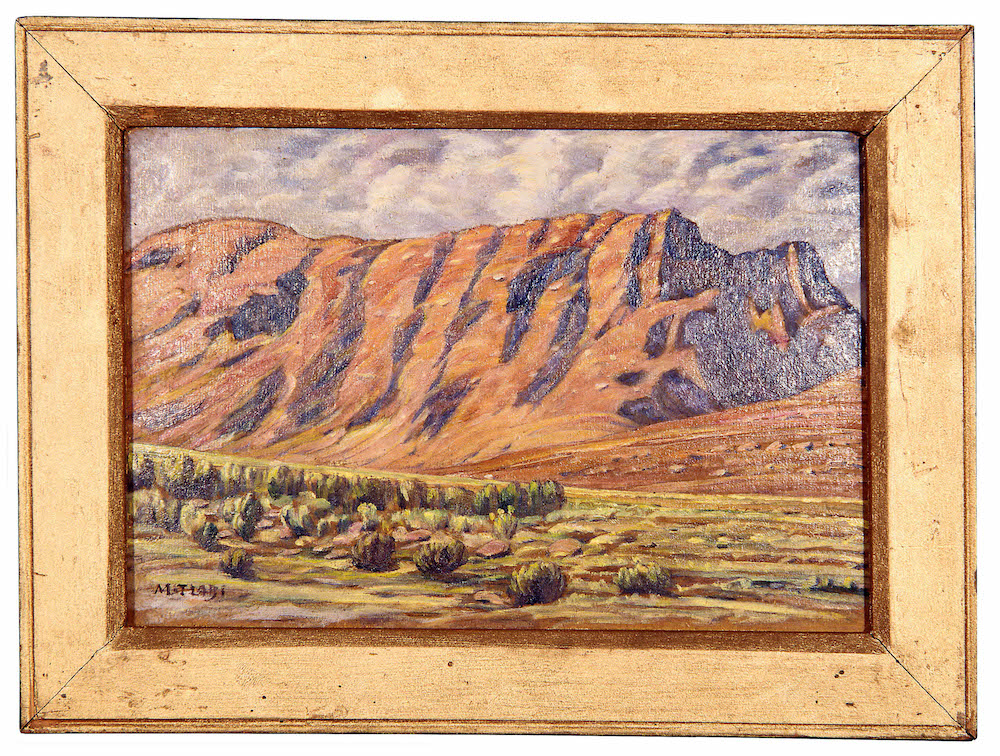

Art by Moses Tladi.

Leaving the Wits Art Museum at the tail end of the Moses Tladi exhibition, I’m a mix of excitement at the resurrection of this genius and sadness while pondering the pain that colonial-era black artists endured.

Tladi smashed stereotypes and prejudices with a humble paintbrush and canvas. Despite artificial race-based hierarchies spanning all spheres including arts and culture, this painter’s work defied the odds in 1928 to reach the Holy Grail that was the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG).

The sadness while sampling Tladi’s work at Wits doesn’t derive from the engineered demographic that was allowed to view his exhibition at the JAG down the road those nine decades ago, but to learn that he was barred from attending his own show. It’s hard to swallow, but is nonetheless a window on to an era.

Years later, Gerard Sekoto’s Yellow Houses painting was accepted by the JAG but that could not open the gallery’s doors to him either. He went in nevertheless, disguised as a cleaner, to see his now-famed work on display. Among others, the national gallery (now Iziko) in the Mother City also flashed a whites-only card.

Born in 1903, Tladi’s cohort of contemporaries included Henry Jordaan, Ernest Mancoba, Rita Ngcobo and Hezekiel Ntuli. Add to that list the iconic Sekoto, who died in exile in France in the dying days of apartheid, and John Koenakeefe Mohl, Tladi’s protégé and friend who went on to become a grandee in both Botswana and South Africa. Mohl’s portraiture “remains exceptional within the context of South African historical paintings”, notes Elza Miles in Land and Lives: A Story of Early Black Artists.

That generation was enserfed by laws that conscripted them into such jobs as farmhands and, like Tladi, gardeners. The Land Act of 1913 turned Africans into “squatters” on their ancestral land, as Sol Plaatje noted in his seminal Native Life in South Africa.

Tladi’s works are poignant yet charming. His repertoire brings to life panoramic vistas of many sites in Limpopo’s Sekhukhuneland, the Free State and in Magaliesberg (Mogalesberg, actually). The Crown Mines painting is a reminder why the newspaper Umteteli wa Bantu described him as a “native genius” as soon as his work went public.

Taking in his Jozi landscape paintings is akin to wandering back to almost a century ago when the town-like city of gold was a junction of brotherhood, raspy air and serenity.

Tladi also produced portraits of animals and ordinary people going about their business in urban and rural settings. Flowers also made his range. Beneath these paintings’ prettiness is a tale of pain that abbreviated the life of this husband and father of four in 1959.

It is no accident that the artist, who Miles contends “had reached maturity as a painter” by the age of 25, died just three years after state land grabs spewed his family from their leafy north Kensington B home (now Bryanston) into the treeless, dusty Soweto of matchbox houses and squatter camps.

That Tladi felled trees in anger at their suburban home after being forcibly removed is no footnote to history. Nor is the fact that he never lifted a brush or opened the box filled with his works after that day.

The heartache was too much, daughter Rekiloe Tladi’s letter related in the biography The Artist in the Garden: The Quest for Moses Tladi by Angela Read Lloyd. Her father poured his heart out in letters in the wake of forced removals.

Interestingly, Read Lloyd is the granddaughter of Herbert Read, the man who employed Tladi as his gardener in his Parktown home and who later introduced him to Howard Pim, who would be instrumental in Tladi later exhibiting at JAG.

Back to the Wits Art Museum on a wintry highveld afternoon, where the admirers who sampled Tladi’s installation drool. I drool too, involuntarily groping the past. A handful of visitors snap nearly every one of his works on exhibition here.

It was not for nothing that he received public acclaim in the 1920s. Still, the right jeered. Volksblad, singling out Tladi by name, was confounded by the “artistic sense of the native”. The Star wrote that there was “naturally good deal of the primitive” about his paintings, adding that they were “surprisingly good”. Where was the surprise? The question is rhetorical. After all, as Umteteli wa Bantu aptly asserted: “artistic ability is not affected by the colour of the colourer”.

An old New African clipping cites a now-familiar anecdote of when Tladi’s peer, Mohl, was approached by an admirer. This “European woman” (as per the lexicon of the era) advised Mohl not to focus on landscape painting, for that genre had supposedly long been perfected by white artists.

“But I am an African and when God made Africa, he also created beautiful landscapes for Africans to admire and paint,” Mohl reportedly retorted with a smile.

Read Lloyd speculates that artists like Mohl and Tladi had to overcome more hurdles to woo buyers than white artists did, despite producing exceptional works.

Embarrassingly, the Rupert Museum emerges as a potential case study. With a collection pegged at R300‑million by art consultant Ian Hunter, it boasted at least two dozen Irma Stern paintings on display at last check – but absolutely nothing by top-rated black painters.

Think Tladi, Sekoto, Mohl and their contemporaries, not to mention George Milwa Mnyaluza Pemba, another prolific painter who went on to, albeit posthumously, be awarded the Ikhamanga national order for his portraiture.

“A collection tells a story and the story the Rupert Museum collection tells is a reflection of the dominant white culture of that era [1940-1970],” Hunter told Art Times in 2014. “The museum would certainly benefit with the inclusion of the major black artists from that period to make the collection more inclusive and representational.”

Rupert Museum curator and administrator Robyn-Lee Cedras said in the same article that the period the museum focuses on was “a very difficult time for black artists to produce work”, which supposedly caused many of them to resort to easy-to-sell subgenres like “township art”.

The marginalisation of black people by lawmakers, and those in charge of purse strings, is nothing new. Deriding works produced by black painters as low grade when evidence contradicts this tired narrative fails to produce an adequate degree of introspection.

It is tempting to speculate how far the highly rated Tladi and his contemporaries would have gone if it hadn’t been for the colour bar and institutional prejudice. What is for sure is that his paintings were rock-star material that unfairly missed out on recognition by way of sales.