Former president Jacob Zuma made the comments while addressing supporters outside the Pietermaritzburg High Court. (Reuters)

NEWS ANALYSIS

With the steady drip feed of #Gupta

Leaks it’s easy to forget the governance and development issues that South Africa should be prioritising.

South Africans are at war – with shadowy foreign forces, with each other – and we’ve all become war correspondents, taking refuge in nihilism and gallows humour while our economy shrinks and our treasures are stolen.

Just five years ago we still had the façade of a functioning government and economy, and our greatest embellishment of this façade was the National Development Plan (NDP). It was an ambitious and thorough attempt to change the trajectory of our economy and our society so that, by 2030, we would have broken the back of poverty, unemployment and inequality.

The NDP now looks dead in the water. It certainly did not enjoy universal buy-in when it was launched, but it represents a time when South Africa took itself seriously enough to plan for its future. It also remains the only yardstick by which to measure the President Jacob Zuma administration, as if it were a normal government interested in improving the economy and the lives of its citizens.

We now know that Zuma’s Cabinet reshuffles were about putting the right cronies in charge and not about fine-tuning socioeconomic development. But examining the NDP is still a useful exercise to measure the distance between where we are and where we had hoped to be.

The NDP planned for a period of growth and development between 2010 and 2030, during which time the number of jobs would increase from 13-million to about 24-million and unemployment would be slashed from 25% to just 6%. The scope of the NDP was far more comprehensive than this — it included plans for energy creation, foreign policy and societal transformation — but it was built around the skeleton of massive job creation.

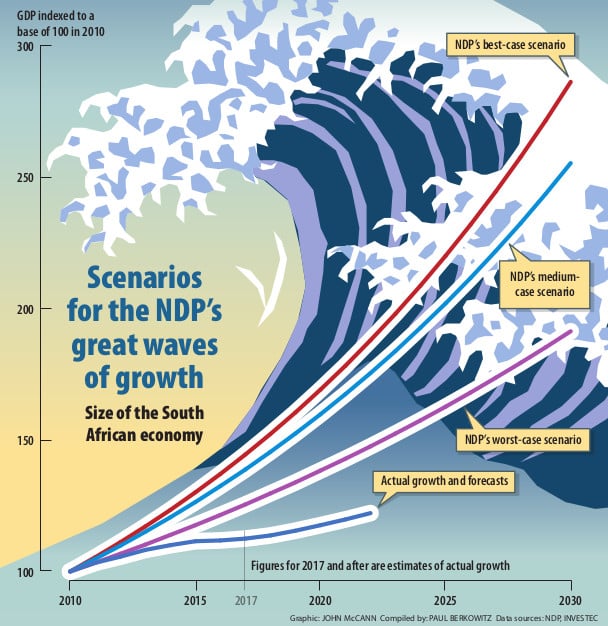

This job creation, in turn, was predicated on sustained high levels of economic growth: 5.4% a year under the best-case scenario and 3.3% a year at worst. The cumulative effect of this growth would have been an economy in 2030 that was between two and three times the size of its 2010 counterpart.

The NDP envisions that any shortfall in job creation would have to be counterbalanced by an increase in the number of short-term jobs (or “job opportunities” as they are euphemistically called) that are provided through the expanded public works programmes.

We know now that we have barely skimmed the lowest of these growth targets; the economy grew by 3.3% in 2011 and growth in the past five years has averaged just 1.6% each year.

The accompanying graphic shows the compounded effects of such low growth, not so much anaemic as bloodless, more paraplegic than pedestrian. Using 2010 as an index, the economy grew by just 12% between 2010 and 2016, compared with a best-case projection of 37% and a worst-case projection of 22%. In other words, our economy’s actual growth since 2010 has been a little more than half of the worst-case scenario envisioned by the NDP.

For the country to reach the NDP’s growth and employment targets it would have to grow by an average of 3.9% for the next 14 years to achieve the worst-case scenario and by 6.9% to achieve the best case. The projected growth for the next five years isn’t close to these numbers: a leading bank has forecast gross domestic product growth to meander along between now and 2022 at below 2% a year, as reflected in the graphic.

If these low growth numbers are maintained for the next six years, the targets for the past eight years become almost impossible: 5.8% growth a year for the worst-case scenario and 11.2% for the best. These growth targets would be ambitious for a China, an India or an Ethiopia; they’re patently unrealistic for South Africa.

There is far more detail in the NDP than just a shortlist of macroeconomic targets to achieve or to miss.

There’s a breakdown of jobs to be created by sector and the necessary sectoral reforms to achieve these jobs targets. There are targets for renewable energy generation, for continent-wide trade agreements, for the training of artisans and for the increase in the number of PhD graduates. There are descriptions of the microeconomic and social reforms that are needed for increased community safety, for rural development and for social and cultural cohesion. Some of these have clear numerical targets but other achievements are more abstract.

What is clear is that we can’t talk about putting meat on the bones of this ambitious national plan when the skeleton itself is riddled with osteoporosis. And this analysis of our growth and development shortfalls barely touches the rot that has infested our economic and democratic institutions.

The NDP’s authors apparently never imagined a day when the fiscus would be so comprehensively emptied and looted by criminals and incompetents, when the treasury’s contingency fund would be reallocated to bailouts for state-owned enterprises and salary top-ups for public servants. We can’t even afford to subsidise the short-term job opportunities when cumulative ratings downgrades threaten the guarantees that the treasury has provided for the nonperforming Eskoms and SAAs of our economy.

We could wait until 2030 to declare the NDP an abject failure, or we can acknowledge now that the Zuma administration has rendered our plans unachievable and our targets unattainable. We’ve become so fixated on a future without the Guptas and so numbed by the broken promises of Zuma and his coterie that we’ve neglected to measure our progress by normal standards.

By whichever measures you choose to analyse, the Zuma administration has come up short. We’ve moved backwards in terms of unemployment, fiscal stability and future prosperity.