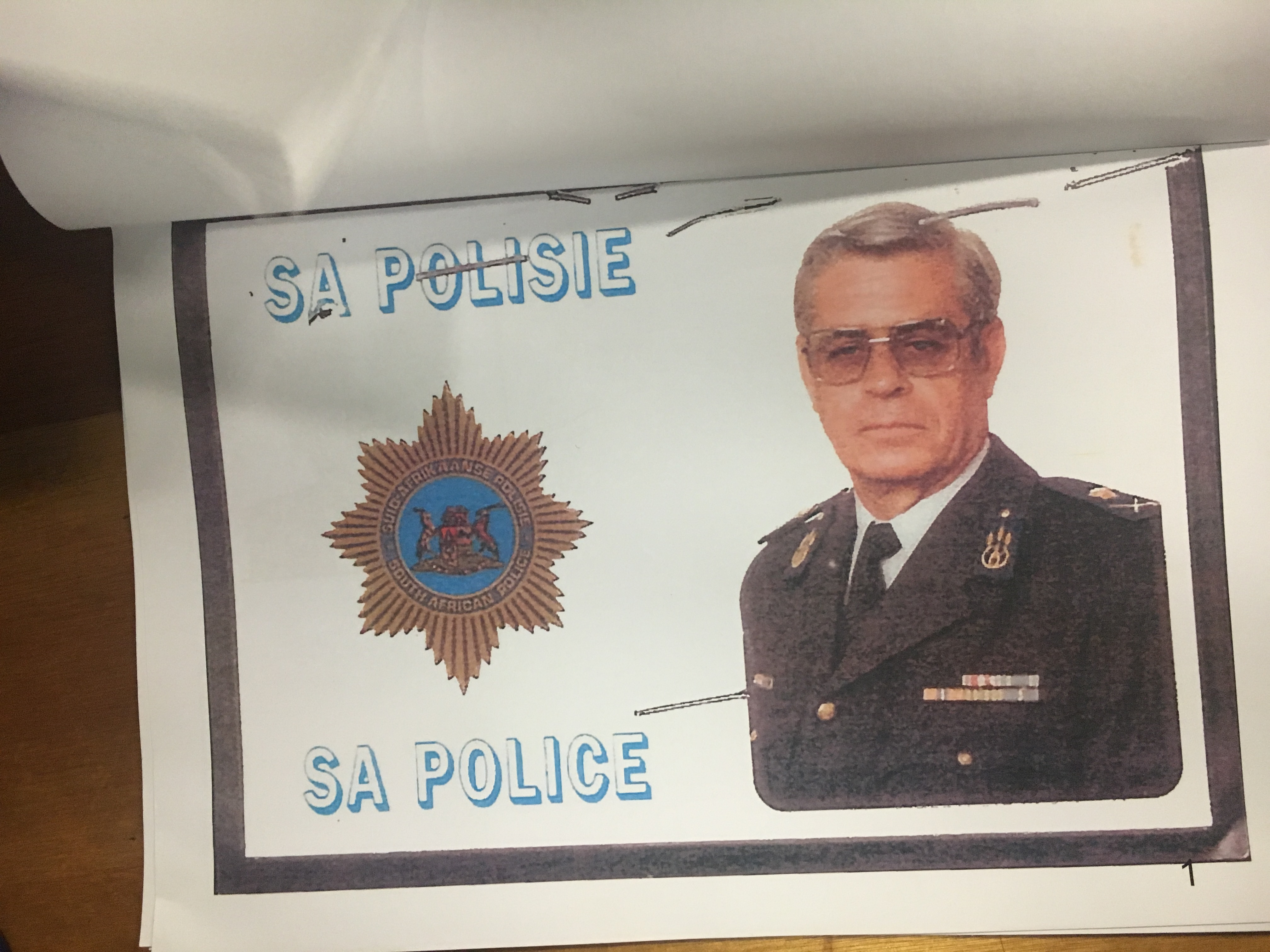

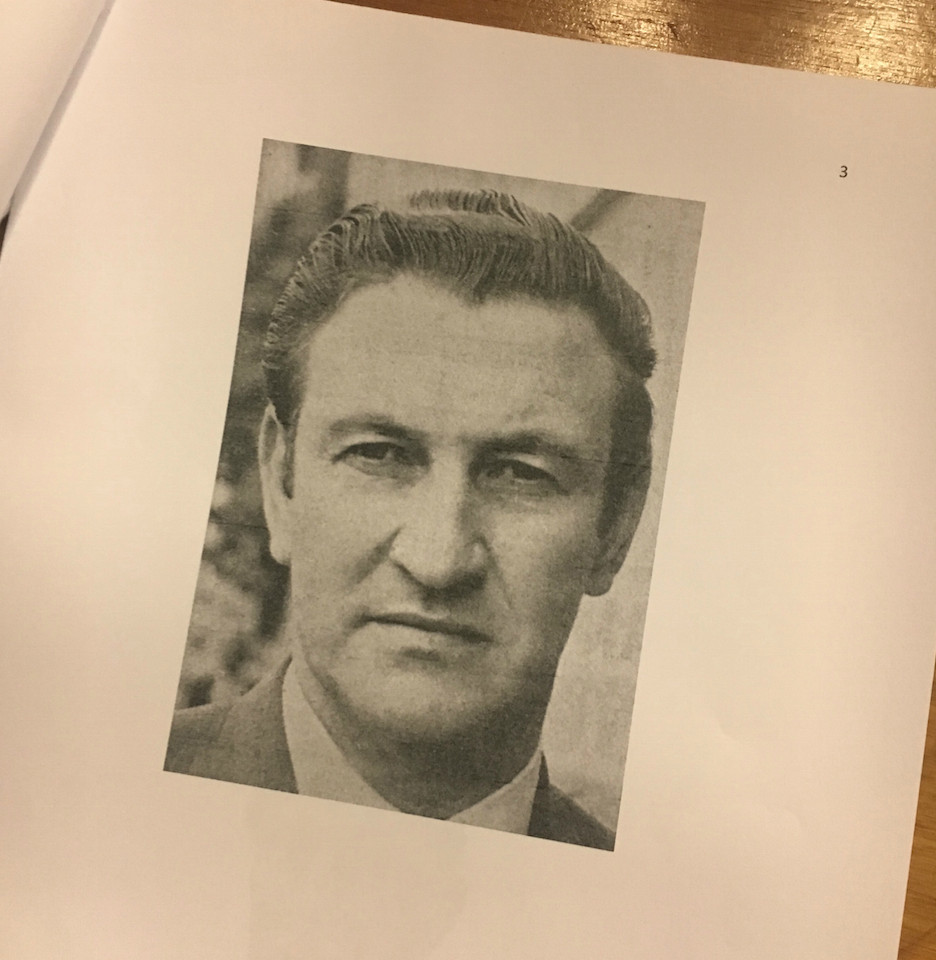

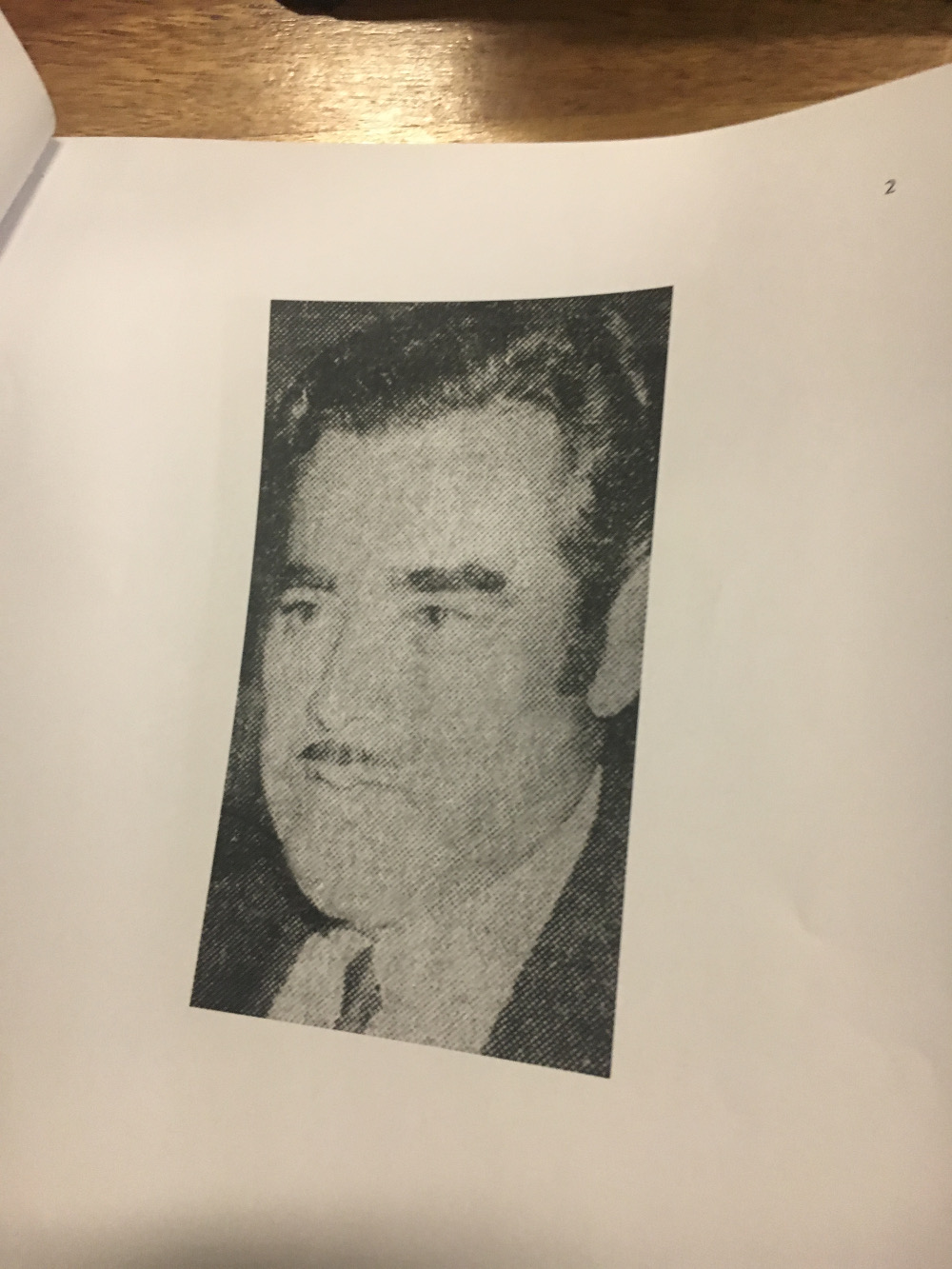

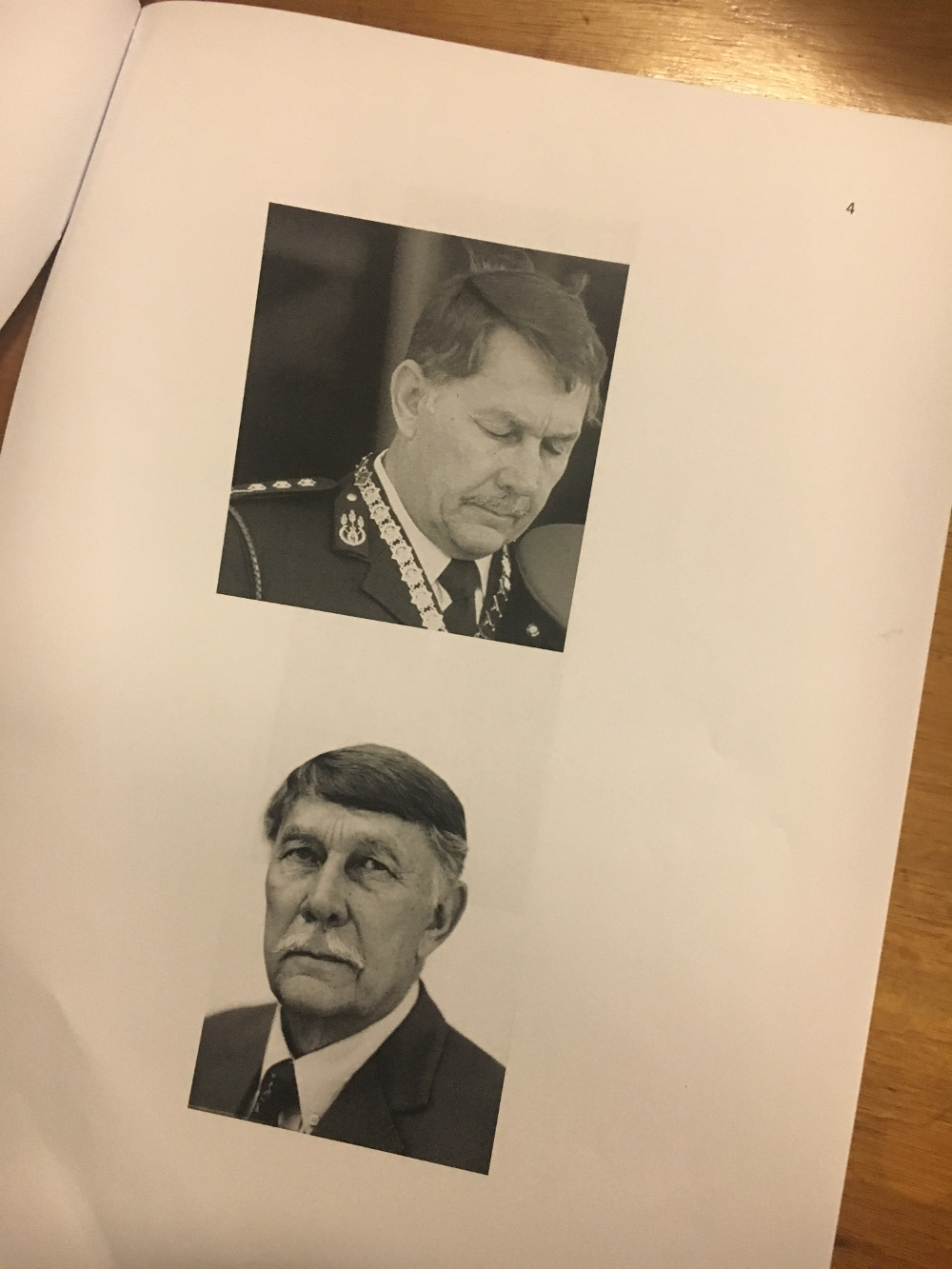

Johannes Van Niekerk and Captain Johannes Gloy.

Anti-apartheid activists Ahmed Timol and Salim Essop were interrogated by the same Security Branch officers at the time of their detention in October 1971. Allegations of torture have been at the centre of the inquest into Timol’s death, and Essop, in a photo identification at the inquest, showed presiding Judge Billy Mothle the men who had tortured him.

On October 26 1971, Essop was taken to hospital after he fell into a coma as a result of the injuries he sustained at John Vorster Square in Johannesburg. In affidavits submitted to the first inquest in 1972, two of the apartheid security policemen who interrogated him also admitted to interrogating Timol before his death. Their names are Captain Johannes van Niekerk and Captain Johannes Gloy.

Both Gloy and Van Niekerk had been accused of assaulting detainees prior to Timol and Essop’s detention in 1971. Van Niekerk was convicted of two counts of assault in May 1960 of an injured detainee at Brooklyn police station. He later died from his wounds. Complaints had also been filed against Gloy for assaulting detainees in 1970 and 1971.

The two were cleared of Timol’s death in the 1972 inquest, when presiding Magistrate JL de Villiers held that Timol killed himself.

The Timol family believes that Timol was tortured severely until he was in a coma or barely conscious at the time of his death. Timol died on October 27 1971 after he allegedly “dived” from the 10th floor of John Vorster Square.

On Friday, Essop was handed two photo albums with images of apartheid policemen and gave the names of some of the police officers he recognised. At the time of his detention, Essop didn’t know the names of his interrogators, but sought their identities later.

“After my release, I went back to the [newspaper] articles and compiled a list of names,” he said.

When Essop was admitted to hospital, his family applied for an urgent interdict to stop the police from further torturing him. He had been slapped, suffocated with a plastic bag, forced to imitate sitting on a chair for hours, and sleep deprived for four and a half days, he said. Two judges found in favour of the Essops and ordered the police to stop torturing him.

Essop was emotional as he looked at the images of Gloy and Van Niekerk. He made an effort to hold back tears.

As he saw the images of the apartheid cops, he would simply say: “He was one of my interrogators and torturers.”

“They had carte blanche to do anything”

Timol and Essop were arrested after the car they were traveling in, a yellow Angelia, was stopped on October 22 1971. Police allegedly found anti-apartheid pamphlets the two were said to be distributing. Liberation pamphlets and their dissemination was banned by the apartheid regime.

One of the policeman who arrested the two was Sergeant Leonard Kleyn. Essop testified on Friday that Kleyn had also assaulted him and Timol. Kleyn, in a statement after Timol’s death in 1971, said he never assaulted Timol and that Timol was never assaulted in his presence.

The sergeant arrested Essop and Timol at a roadblock that had been set up on Fuel Road, Coronationville. Timol and Essop were taken to Newlands police station and then to John Vorster Square. Essop was tortured on the 10th floor in room 1013 – one of the “waarkamers” (truth rooms).

Essop testified that in the four and a half days he was detained, at least 15 police officers tortured him. There were two or three policemen with him at a time, and they would take it in shifts to deprive him of sleep.

He said that was likely that he and Timol were interrogated by the same policemen, who moved between room 1013 and room 1026 – the room where Timol was allegedly tortured and fell to his death.

“They would come to me with a certain question with information they could only get from Timol,” Essop said.

The torture took place in “vaults” – which he has described in previous testimony – attached to the rooms. Among the policemen who tortured him, Essop identified Security Branch cops Major JH Fourie and Lieutenant Colonel WP van Wyk.

At the 1972 inquest, Van Wyk testified that he interrogated Timol from 3.15am to 5.30am on October 23. He requested Van Niekerk and Gloy to help with the interrogation; they arrived at 6am that morning.

He would then interrogate Timol again, according to his testimony, from 8:30am to 19:30pm on October 25 – two days before Timol’s death. He said he had not assaulted Timol and Timol was never assaulted in his presence. There were no injuries, he said.

At the current inquest, Essop testified that Van Wyk and the other security policemen were brutal, but firmly believed their actions were just.

“They have no morality about this, they didn’t think they were doing any wrong,” Essop said.

“They had carte blanche to do anything.”

Waiting for the truth

Last week, Joao Rodrigues dominated the reopened inquest with his testimony that ran for three days. The former apartheid police clerk, who is allegedly the last person to see Timol alive, testified that an agile and healthy Timol “dived” to his death.

Rodrigues is the only apartheid policemen still alive who is known to have been involved in the Timol case. Evidence presented to the inquest has countered his testimony, and he has been warned that the Timol family will seek his prosecution for murder or accessory to murder.

Gloy, Van Niekerk and Rodrigues never appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and therefore do not have amnesty. The Timol family lawyers are trying to track down when Gloy and Van Niekerk died.

General Johan Coetzee, who Essop identified in a photo, was an apartheid police commissioner who told the TRC that he had not condoned political assassinations. But at the inquest, testimony from Security Branch policeman Paul Erasmus disputed Coetzee’s claim to the TRC.

Essop said on Friday that the inquest is an opportunity for apartheid cops to tell the truth and “come clean”.

“Maybe this is the unfinished business the TRC didn’t complete,” he said.