Misunderstood: In his role as the surgeon-general

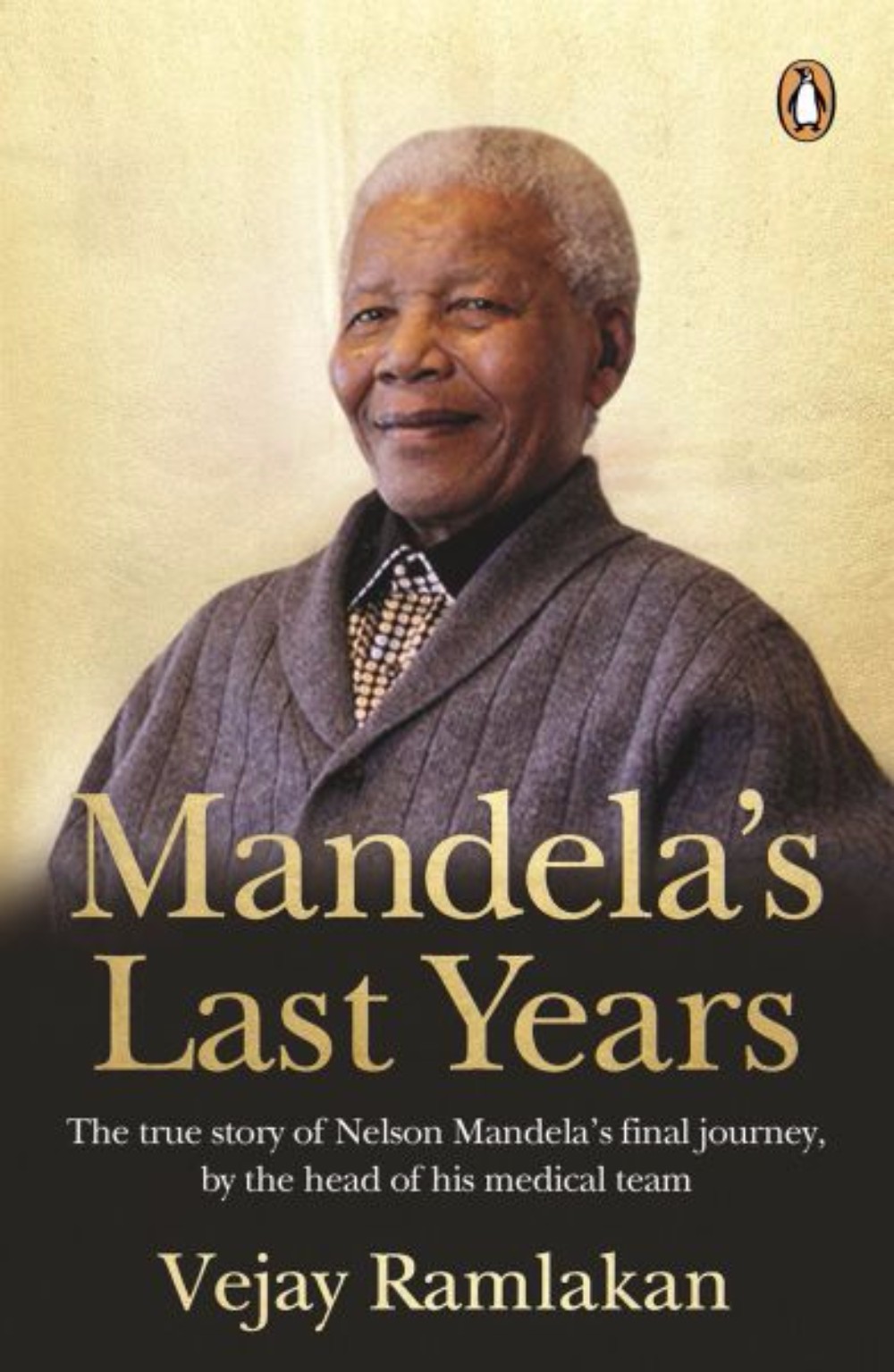

MANDELA’S LAST YEARS by Dr Vejay Ramlakan (Penguin Randomhouse)

Price: Recalled like Mbeki

When I received Mandela’s Last Years from a friend as an early birthday present, I threw it in my bag and forgot about it. I did not know that in less than two weeks it would have become a collector’s item. And the moment it was recalled, like many South Africans, I now had a compelling desire to read it.

[Dr Vejay Ramlakan’s book ‘Mandela’s Last Years’ (Gallo)]

[Dr Vejay Ramlakan’s book ‘Mandela’s Last Years’ (Gallo)]

Written by Dr Vejay Ramlakan, Mandela’s Last Years is told in three parts. The first part, subtitled A Life of Strength, is the shortest section of the book. It is also, I suspect, the section that resulted in the book being recalled.

Although the book begins with Nelson Mandela’s medical history, purportedly gathered from the public domain including Mandela’s memoir Long Walk to Freedom, the book for me really begins when Ramlakan examines Mandela for the first time. This happens during an ANC conference after Mandela and Ramlakan’s release from prison. Except for hypertension, Mandela is said to be in good health.

It is a temporary engagement because Dr Nthato Motlana is still the chief physician for Mandela and his family. But it is Ramlakan’s book that shows us just how important Mandela’s health was to the state, both during and after apartheid.

Through Mandela’s health, we see some growing tensions of the then new South Africa. For instance, a year into his presidency and with Mandela’s health being a responsibility of the state, Ramlakan recounts an anecdote that resulted in fireworks between members of the former South African Defence Force and those of the ANC now in the integrated military.

He tells of Davison Masuku presenting a paper arguing for “a dedicated presidential medical unit’’ during a meeting, a stance supported

by Ramlakan and Ashwin Hurribunce. This angered the incumbent surgeon general, Lieutenant General Niel Knobel, so much that it only became a full unit in 2005, a year into the second term of Thabo Mbeki’s presidency.

If there are any questions regarding medical ethics, I think they should have been addressed years before — as far back as 2001, in fact.

On page 23, Ramlakan recollects Mandela’s diagnosis of prostate cancer: “Shortly after his 83rd birthday, the diagnosis was made public, such was the need to be transparent about his life.’’

In July 2001, Rapport newspaper interviewed a urologist who had been consulted on Mandela’s health. The urologist said the treatment Mandela received was wrong and Rapport sold a lot of newspapers.

“Interestingly, nobody complained about the ethical appropriateness of this discussion playing itself out in the media,’’ Ramlakan writes.

In 2001, Graça Machel was already married to Nelson Mandela. If one wonders why she and everyone else who spoke against the publication of Mandela’s Last Years did not say anything to condemn this disrespect of Mandela’s privacy by Dr Lance Coetzee and Rapport, they should not wonder for too long. Further in this same section of the book, the family and staff dynamics in Madiba’s circle come to the fore. These dynamics, rather than any revelation of Mandela’s health, seem to me to be the reason this book was recalled.

Ramlakan writes on page 31: “While the military was officially responsible for his care, allowance was made for others to treat the former president as well, often at his specific request. For me and my staff, it was a tough balancing act. In the normal course of ageing, geriatrics rely on their support staff or families to arrange their healthcare. In Mandela’s case, there were three branches of the family — those from Evelyn Mase; those from Winnie Madikizela-Mandela; and then the expectations of his wife, Graça Machel. In addition, there was the Nelson Mandela Foundation and, in particular, his personal assistant Zelda la Grange who had assumed decision-making powers regarding his health.’’

Mandela spent all his Christmas holidays in Qunu in the Eastern Cape, but in 2009, his year-end vacation moved to a lodge owned by insurance mogul Douw Steyn in the Waterberg in Limpopo.

According to Ramlakan, it was a decision made by the foundation employees and Machel and seemed to be a decision that upset the rest of the family. They did, however, join the patriarch but departed on Christmas Eve because the group was too large.

But during lunch, attended by Steyn’s guests, the host explained “his plans for a mega property development to be called Steyn City in an area north-west of Johannesburg. In the ensuing conversations, staff noticed a change in Mandela’s mood. He was visibly angry, presumably at something someone had said’’ (page 33).

Mandela was upset enough to leave the party and ask the security staff to contact his daughter Makaziwe. “She spoke to Mrs Machel and requested that Mandela be returned to Johannesburg’’ (page 34).

Unable to get a helicopter, Mandela would leave by road.

Ramlakan also takes a swipe at Zenani, another daughter of Mandela. During the 2010 World Cup she smuggled in the Spanish team for a photo opportunity with Mandela, despite his delicate health at that time.

I get the feeling that perhaps Machel, her advisers and every Mandela family member who opposed the sale of Mandela’s Last Years may have read only this section and decided these were not family secrets they were willing to divulge to the South African public. Had they bothered to read the rest of the book, they would have read a wonderful homage to the statesman by the man who was on his medical team in Mandela’s last years.

A troubling insight is how former minister of defence Lindiwe Sisulu seems to have had little confidence in this medical team, despite its dedication to the famous patient. Ramlakan recounts how she brought a team of medical doctors from Cuba. Aware that Sisulu was their political boss, the medical team generously stepped aside to allow the Cubans to examine Mandela. The Cubans, who could speak little English, managed to communicate to the team through one of the South African National Defence Force doctors who had studied in Cuba. After a few weeks, the Cubans reported to Sisulu that the team had done a good job. It seemed it was only at that stage that Sisulu became confident that the team knew what it was doing.

The only people who really come off badly in this book are La Grange, Sisulu, a daughter who brought Bill Clinton to Qunu without following protocol, and an eTV journalist who seemed to have had inside information on Mandela’s health when he was in hospital and would ask the doctors uncomfortable questions during media conferences.

Mama Graça is lauded for her grace and her willingness to work with the other two families regarding her husband’s health. She could very well have decided that, as the spouse and next-of-kin, only her opinion mattered.

She is also shown to care deeply for the medical team and, on Mandela’s 95th birthday party in hospital, “the ‘after party’ for the medical panel ended and the night staff took over. After our evening meeting, our team was invited to dinner in the ‘party room’ by Mrs Machel’’ (page 156).

Did Ramlakan break any doctor-patient confidentiality? I am no doctor and not privy to how much one can share, but I did not see evidence of this. I researched some of the medical information mentioned in the book. Much of this was already in the public sphere.

It is ironic that some in the media, who had insisted on knowing every small detail about Mandela in his last years, now claim that Ramlakan had been disrespectful in writing this book and letting the nation and the world that loved him know how he spent his final days.

After reading Mandela’s Last Years I know two things.

I know that I would consider myself very lucky if any of my loved ones had people as devoted as Ramlakan and the medical team he set up, led by Dr Steve Komati. I know too that if I were a Mandela family member, I would not have banned a book that pays such wonderful homage to the Mandela family and the way they negotiated the difficult times during his last days.

South Africa and the world are all the poorer for not being able to read this important text. And I feel all the richer for having it. Thank you, Niq Mhlongo.

Zukiswa Wanner is an official Mandela biographer. She co-authored 8115: A Prisoner’s Home with Alf Kumalo (Penguin, 2010)