(John McCann

A seasonal low, the effects of a protracted drought, those darned Banting enthusiasts and even the Chinese could all be the reason you may struggle to find butter at your local supermarket. And, when you do find it, you can expect to pay 27% more for it than you did last year.

“A major shortage of butter is being experienced in South Africa and we are uncertain how long it will last,” said Jacques van Heerden, the legal, secretarial and human resources executive of the major diary producer, Clover Industries. “As cream is used to make butter, there is actually a shortage of cream.”

Koos Coetzee, the chief economist of the Milk Producers’ Organisation (MPO), said the shortage of butter has largely been caused by consumers switching to full-cream milk and other higher fat dairy products, which has reduced the quantity of cream available for making butter.

Milk production is also down. It is 0.4% lower than last year and is a “natural process, largely governed by climatic and economic factors”, he said.

But, whatever the cause, butter prices are rising. According to the global market research firm Nielsen, the retail butter price was almost 27% higher in March this year than in April 2016. Coetzee said this was the result of both supply and demand.

Demand has been spurred on by the popularity of the low-carbohydrate, high-fat Banting diet, advocated by the prominent sports scientist Tim Noakes, which has led many consumers to switch from low-fat to full-cream milk products.

Added to that are other factors such as a general move towards more natural products as well as consumers’ perceptions changing about plant and animal fats, as scientific proof of the benefits of butter has become better known, Coetzee said.

But Nielsen’s statistics showed that butter sales were 4.4% down compared between April 2016 and March this year, and Clover’s results for the six months ended in December 2016 showed butter volumes decreased by 13%.

According to Nielsen, the demand for margarine in South Africa remained consistent, dipping only 0.8% between 2015-2016 and 2016-2017.

Justin du Toit, an agricultural economist and the owner of the agribusiness consultancy Vuna Agribusiness based in KwaZulu-Natal, said a butter shortage can arise because of both supply- and demand-side factors, including changes in macroeconomic and regulatory conditions.

“Due to free-market conditions and a need to operate at scale and size to achieve a cost advantage in a fiercely competitive global industry, the predominant milk production system in South Africa is now pasture-based with partial supplementary feeding. This gives milk producers in areas with higher, more reliable rainfall and better access to irrigation water a comparative advantage over others,” he said.

Over the past 30 years, the dairy industry has been affected significantly by consolidation, resulting in fewer, larger producers. “A shift in the geographic distribution of milk production from inland to coastal areas has also taken place over the same period because of the comparative advantages these areas offer milk producers,” he said.

According to the MPO, 30.7% of South Africa’s milk is produced in the Western Cape, 28.4% in the Eastern Cape, 23.7% in KwaZulu-Natal and 17.2% in the interior of the country.

“On the supply side, a protracted drought was experienced across much of the country during 2015 and 2016, resulting in lower milk production during these years as farmers tried to cope and adapt to water scarcity and increased occurrence of disease and stress in their herds. Many may have responded by reducing herd numbers, which will take time to build up again over the next two to three years,” Du Toit said. “The dry conditions in the Western Cape are still persisting, which will influence the overall milk supply moving into the summer months of late 2017 and early 2018.”

He added that there is a typical seasonal dip in milk production in the summer rainfall areas during winter because of naturally drier, colder conditions limiting pasture growth. Calving is also staggered to coincide with the spring months when pasture growth increases with warmer, wetter conditions.

He said higher butter prices will give milk processors an incentive to turn more cream into butter instead of other processed products, although there could be a lag as milk production volumes begin to recover.

Coetzee said South Africa normally does not produce enough butterfat and is traditionally an importer of butter. Globally, prices have reached record levels because of shortages in other parts of the world.

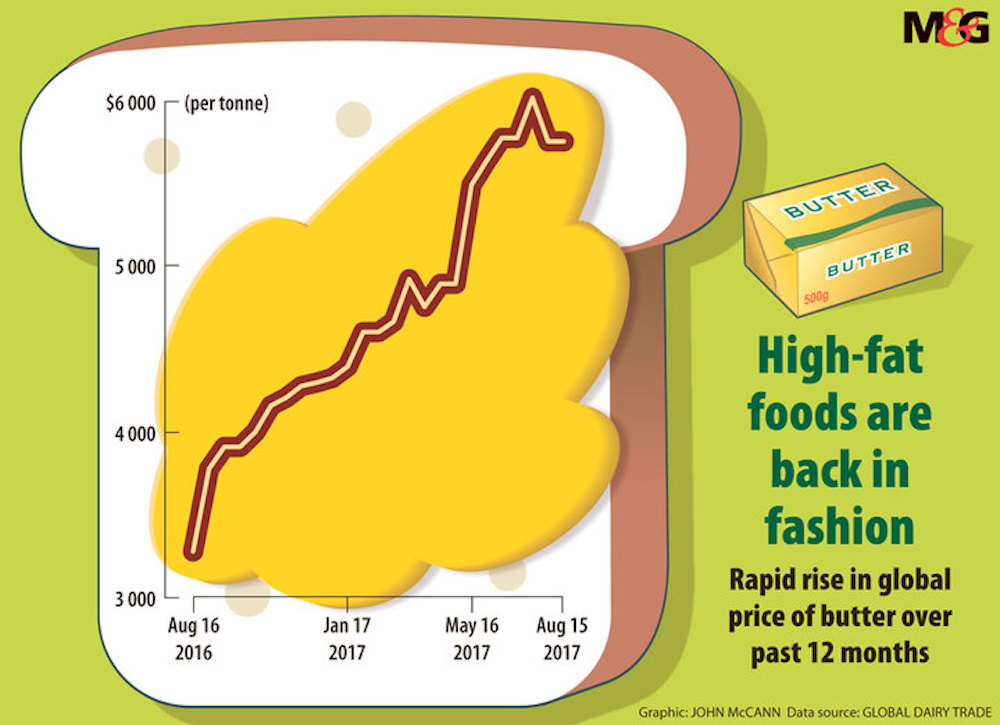

“The price of butter on international markets increased from $3 485 [a tonne] in January 2015 to $5 925 in July 2017, an increase of 70%. At the same time, the price of skimmed milk powder decreased by 12%,” Coetzee said.

Again, the demand for full-cream milk and full-cream yoghurt resulted in a decrease in the quantity of cream available for butter, causing butter stocks in the European Union to drop, Coetzee said.

An industry group for French bakers has warned this will affect the supply and price of cherished pastries such as the croissant.

In the United Kingdom, some dairy farmers have warned that the worst butter and cream shortage since World War II will occur in December, the Evening Standard has reported.

As reported by CNN, the average European ate 3.8kg of butter in 2015 compared with 3.5kg in 2010, and the average American ate 2.5kg in 2015, up from 2.2kg in 2010.

Global prices have also been spurred by a growing demand for butter and other finished dairy products in China. “If China gets hungry for something, it has a wider impact,” Du Toit said.

The United States department of agriculture expects China’s milk imports to jump by 38% this year and it predicts global butter consumption will grow 3% in 2017.

Unilever, which was originally formed through the merger of a margarine-maker and a soap-maker, is getting out of the margarine business as, overall, its global spread sales have declined.