Life and career partners: Letta Mbulu and Caiphus Semenya have spent their lives collaborating in marriage

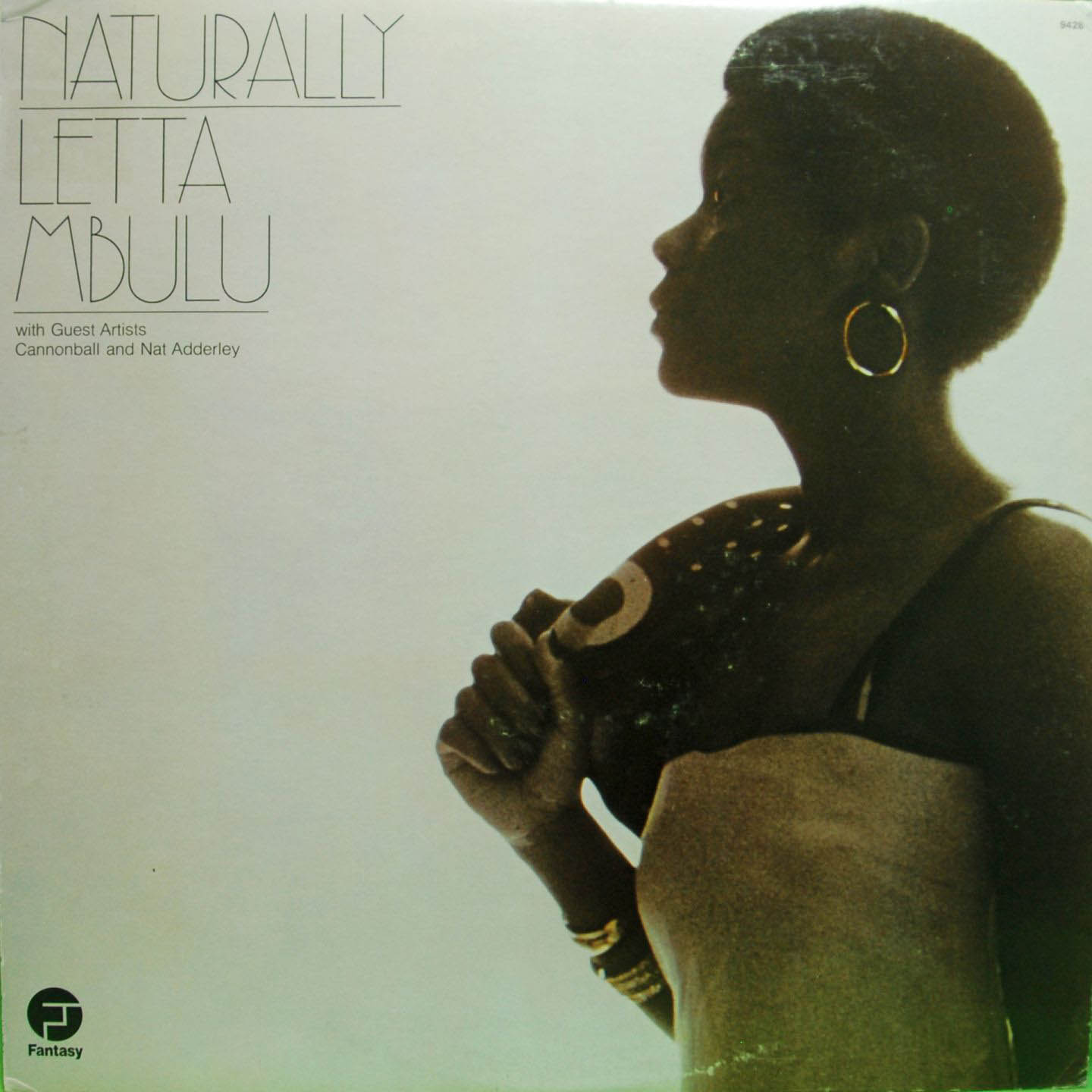

The only Letta Mbulu album I own in tangible form is her 1973 opus, Naturally. In its cover image, Mbulu, in profile and almost in silhouette, is dressed in a strappy number, clutching what may be a jacket that is part of her ensemble. She appears to be heading for the door, perhaps the stars, but she must lay down the law to an unknown, unfortunate sod before she jets off.

Given the tactile nature of the vinyl format, I have looked at that image countless times in what must be close to 20 years. Looking at it now, the image is as important as what is contained therein. Not only was Mbulu the musical embodiment of South Africa’s struggle years, she was also its visual quintessence; defiant but understated, and, as the beaming visage on the rear cover suggests, happy and wilfully free.

The emotional meter of the album resembles the swing of a pendulum, with Mbulu probably lamenting the isolation of exile in Kube, while dishing out assurances to her lover minutes later in Never Leave You.

Naturally, a single snapshot of a prolific career lived out in tandem with her composer-producer husband Caiphus Semenya, like many of their other records, embodies their ethos and aesthetic, codes that have guided their performance careers and lives for well over half a century.

Singing professionally by the age of 13, Mbulu grew up under the spectre of Miriam Makeba, first singing with a group called the Swanky Spots before joining Alfred Herbert’s touring stable of artists, featuring the likes of Makeba, Dolly Rathebe, Dorothy Masuka, Thandi Klaasen, Ben Masinga and Sonny Pillay.

“I used to watch them on stage,” says Mbulu in the lounge of her home in northern Johannesburg. “That’s when I decided ‘I want to do this. I truly want to do this’, because they were so highly professional. I was influenced by all those artists, who were very nurturing, very loving.”

Of them all, it was Masuka’s polyglot style that the singer became interested in. “She was coming from Zambia and her music had a different flavour altogether. The words … She would mix in isiNyanja and use isiZulu, isiXhosa and Setswana. She became a big influence in my singing.”

In the 1950s, Semenya was shipped off to Benoni by his mother to clip his involvement in Alexandra’s gangs. The move thrust him into his extended family’s musical routine, which soon led to more formalised education at Johannesburg’s Dorkay House.

“Benoni was known for music because you had the Woodpeckers, the Harlem Bookies, Ace Buya and the Harmoneers. They had all kinds of groups that were part of the tapestry of the community of Benoni,” he says.

“At school they had choirs like everywhere else, but they also had some extracurricular musical stuff, where they encouraged us to sing songs that were not particularly of the school. The teacher would just say, ‘You and you and you, looks like you could form a group.’ That’s how I became interested in music at school.”

In his early 20s, Semenya would also work with theatre and musical greats Gibson Kente and Theo Bophela, narrating Kente’s Manana, the Jazz Prophet.

In the book Still Grazing, collaborator and fellow exiled musician Hugh Masekela calls Semenya, who was then just developing his songwriting abilities, one of Africa’s greatest composers. Of their early days in the mid-1960s United States, Masekela writes: “At that time, his Bo-Masekela was a mainstay of my band’s playlist. It was a beautiful, rhythmic ballad in the harmonic style common to the folk music of the Tsonga, Pedi, Venda and Ndebele people, peppered with blues chordal progressions, a prominent, contrapuntal bassline and a sweet trumpet melody.”

While Mbulu had been imbibing the fusionist style of the greats she was surrounded by, she says it was a Makeba performance at Birdland in New York that solidified the template to her style.

“She was glamorous, she was stately and the stories she was telling about the people of this country … I said, ‘My Gahd. Why am I wasting my time’. And most of the songs were done in African languages. She would maybe take one, two or three songs in English. And the audience was eating that up. I said, ‘Ja … that’s exactly what I want to be about’. And really, that was a turning point in my life.”

Mbulu and Semenya met around the staging of King Kong, the 72-cast musical, which featured Makeba as Joyce. Connecting again in the US, where Semenya had landed after taking part in the Alan Paton-written show Sponono, Mbulu and Semenya discovered their complementary talents, beginning a prolific career as composer and performer.

“I didn’t know Caiphus could write,” says Mbulu of their early days in the US. “He was working on something and he called me over. He said, ‘Do you like it?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, It’s okay.’ He said, ‘Well, Miriam Makeba is already recording it.’

“Then he played something called Nomali on the piano. I said, ‘Wow, you really can write … I’m really fortunate you can write’. That’s really when I knew that everything I was about as an artist had to take a different turn altogether.

“I said, ‘You know what; you write and, if I don’t like it, I’ll tell you I don’t like it. But you have to write.’ And that’s really how we evolved. It was from listening to other artists and trying to find ourselves in the midst of what was going on in the States.”

Of course, Mbulu wrote too, including a number of songs that were sung by Makeba herself.

Although Mbulu and Semenya were able to reach the apex of their respective and conjoined careers in the US, working within the confines of a nascent music industry there and branching off into film scoring and acting, it was the alchemy of their approach that ensured their longevity.

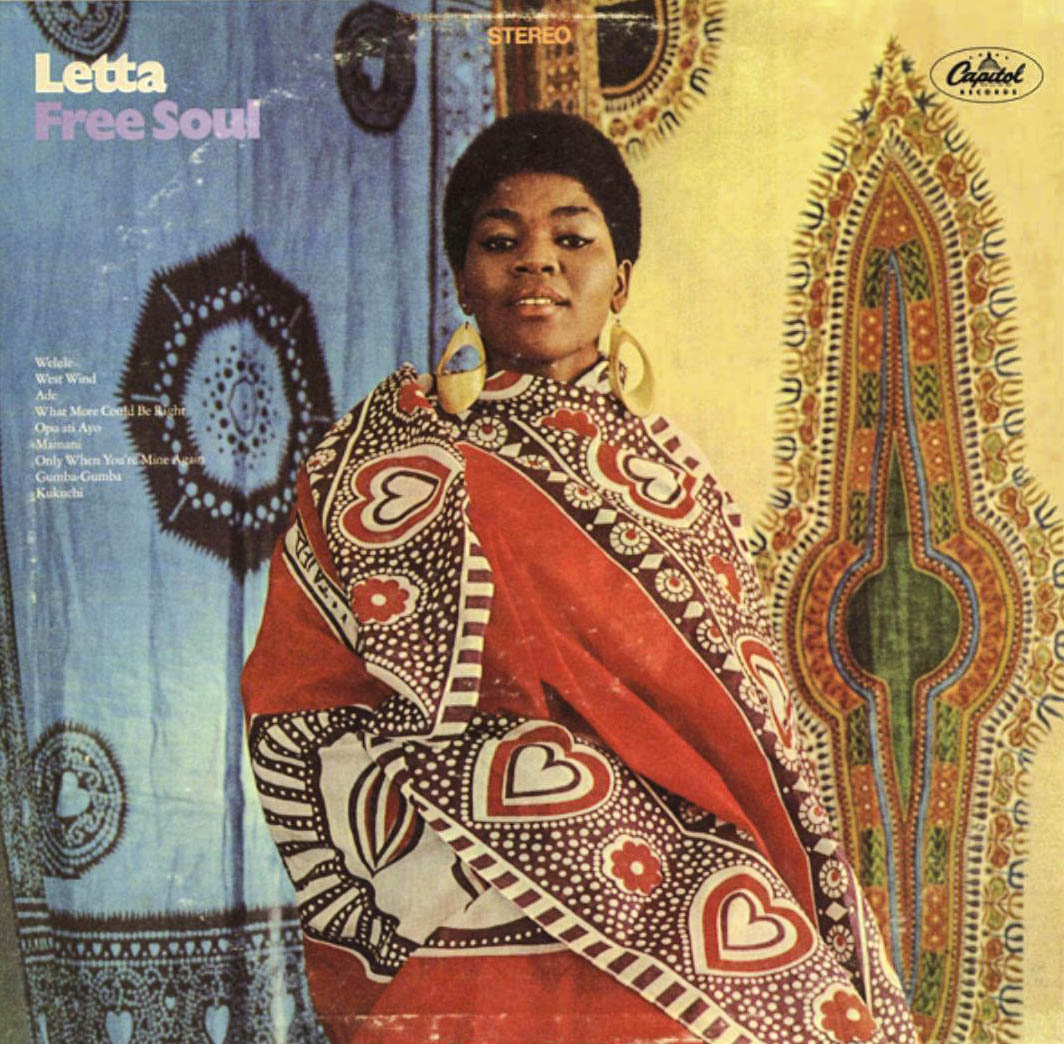

For example, a biography on the Macufe website notes that at Capitol Records, where Mbulu released the gorgeous but low-selling Letta Mbulu Sings in 1967, producer David Axelrod dropped her surname for palatability on her following album, Free Soul, but it featured “the beautiful young Letta on the cover swathed in colourful Afrocentric clothing”.

Sonically, the music was underpinned by South Africa’s urban musical trajectory, infusing mbaqanga with contemporary American styles like soul and funk.

Thematically, a song like What Is Wrong With Groovin’ is instructive of Mbulu’s tone, somewhere between the overtly political and the wisened, while simultaneously concerned with something else — the lived urban experience, especially in as far as it pertains to her right to be ungovernable.

“Most of those artists that influenced us,” Mbulu says from the comfort of her couch. “There was a certain spirit in them that we can’t describe. It was a form of protest. They didn’t spell it out. The only time you saw it was when they hit the stage. That spirit permeated and some of us caught it, both hands, and we ran with it.”

Her emotional range, her held notes, sometimes sturdy and at times quivering, transformed a listening experience curated by music industry imperatives into something altogether more transcendent and human.

“From the time I was performing, the music has made serious strides,” she says. “It’s a tradition. South Africa is a voice country. We sing. We are good at it and that’s a fact. We have choirs that are slamming. And that’s a fact. The only thing that has not moved is the industry side of music. The companies are still fumbling to take an artist, groom them and let that artist grow. We grow because we have to grow, but what we need is guidance as artists. So that we know why we are singing, we know why we want to play.”

The future

The business of the day, even as I get overwhelmed by history, is that Semenya and Mbulu are finally bringing to fruition what has been a 20-year plan to establish the National Academy of Africa’s Performing Arts. It’s an idea they cherished long before resettling in South Africa, first dropping it at the doors of Nelson Mandela’s presidency in the mid-1990s.

“When we came back home, we were already full of these ideas to influence the younger artists to be themselves, to unhinge what was in their minds,” says Mbulu in her typically measured and emphatic manner.

“In the US, another thing that fuelled us was watching artists who were professionals and that came about because they were schooled. Music schools were everywhere and kids started at around eight. By high school they knew what their creativity would be about.

“We said to ourselves, ‘How we wish our country was like that, where our kids could actually express themselves and be able to bring everything that they feel, and be able to write it down’. So when we came here we were ready. We said we need to do this for our people, for the artists of this country.”

But the plan got lost in the bureaucracy of democracy, being shifted from arts department to arts department with each successive presidency. The envisaged academy will be about much more than musical rudiments and is premised on the egalitarian formula that guided their evergreen musical experiments. It is also based on their scathing analysis of the country’s music industry.

Speaking at a Durban International Film Festival panel about their career in scoring films, the couple said, in their minds, the country has no music industry to speak of.

Seated in their Johannesburg home, they put this contentious statement into context.

“People who work in the mines have a union. It’s an industry,” Mbulu says. “You have a union that will protect you. You have a union that will go to Parliament to lobby for the miners.

“We do not have that in South Africa. In America, you can never work [as an artist] if you are not part of a union. Your contract protects you against the venue that you work in. You get loans. If you want to buy an instrument, say a piano, they will get you that piano, at 1% interest. You see what I’m saying. In South Africa, our artists are always scrounging.”

Mbulu mentions a show they often watch on TV to sketch the specifics of the curriculum. “I don’t know if you have seen a programme called Culture Express, where they have orchestras, symphonies that use traditional instruments. These young people go to school and learn all the rudiments of music, but they go back and play their own traditional music, with their own traditional instruments and it is so fantastic. So we watch these things and we are so fascinated by them. We want to incorporate traditional instruments but we also want to modernise them, so when you play them you hear all these electronics and it’s new and fascinating.”

During the film festival panel discussion, to make their point, Semenya said the rudiments of mbaqanga music were generally not taught in music schools. “One of the most difficult things is writing music in three chords, so we want to challenge these kids,” he said.

Referring to the academy, they mention dance, theatre, film, instrument modification and repairs, a business curriculum — and then they draw back for fear of divulging too much.

Listening to them speak, their resoluteness about centring our rich heritage in our cultural output, I can’t help but wonder about the extent to which their return from exile has been an alienating, perhaps isolating experience. A song like Not Yet Uhuru, the title track of Mbulu’s 1996 release, is nothing if not prophetic, a pre-emptive strike that may or may not have set them on a collision course with an ANC newly in power; a power that would fit snugly into the machinations of the apartheid regime.

Although the pair have performed consistently since their return, their recorded output, at least to a casual observer like me, has slowed down to a trickle.

I broach the idea of self-censorship to the musicians, so brazenly expressed by rapper AKA in last year’s appearance on the American radio show, Sway In the Morning.

“With the song Not Yet Uhuru, there was lot of flak, but because it touched a chord, people said we will protect this,” says Mbulu. “You go to a concert, they demand the song. It’s what you say to your people. That will help you and protect you.”

Semenya adds: “The people who started reggae, the Bob Marleys and so on, they were political prophets. To them reggae is like a hymn book. It is sacred music. But if you don’t understand what it is, you won’t sing what reggae is trying to portray. The same thing with rap. The Kool Moe Dees and the Bambaataas, when they started rap, it was about the social conditions of America. It was social commentary and protest.”

Here, I differ slightly with this legendary couple, trying to argue my case for early hip-hop as initially anti-gang party music (in the vein of What Is Wrong With Groovin’) and Geba rap as advancing the linguistic framework of contemporary isiZulu, but it is a half-hearted attempt.

It is thwarted by my awareness that the nuances of meaning may get lost when the English language on the tongues of nonspeakers, and that their careers have been nothing short of exemplary in so many areas, not least in how futurism is performed and lived.

One can expect the string of reissues, primarily targeting Mbulu’s catalogue as singer, to continue and take a more interesting turn as people try to decipher their vaults, and, in particular, Semenya’s unwavering commitment to the modernisation of pan-African folk music traditions.

This story contains elements of Mbulu and Semenya’s panel at this year’s Durban International Film Festival. Their National Academy of Africa’s Performing Arts, based in Jabulani, Soweto, is under construction. Not Yet Uhuru will be released on vinyl in October