100 year anniversary of Anglo

COMMENT

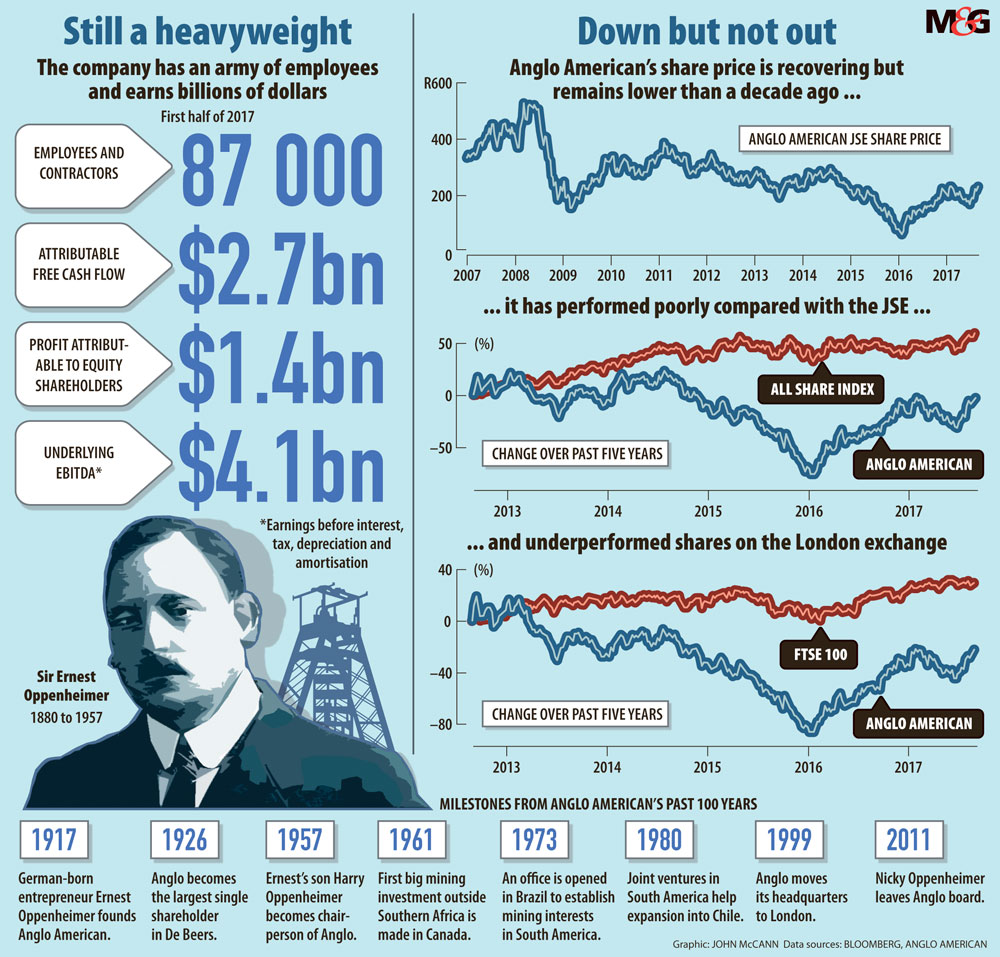

This month, Anglo American marks its 100th anniversary and the company is finding that South Africa is hard to love or to leave. Very few companies survive this long, certainly with their founding name intact.

Anglo has spent the past three years oscillating between a fire sale of its assets to exit the country on the one hand, and the selling of underperforming bits but keeping jewels in its crown on the other. At one point, it seemed its stance changed at every results announcement.

But Anglo finds South Africa is hard to leave because of the quality of assets it has here, which place it in pole position in commodities such as platinum and iron ore worldwide, not to mention the magnificent Vergelegen wine estate in Somerset West.

The country is also hard to love because of an unpredictable regulatory environment, in which poor communication can be a bigger problem than bad regulations and an exhausting political environment.

Anglo’s dominance of South Africa’s economic life is well documented. The company’s evolution into a conglomerate may have been as a result of operating in a closed economy, but exposure to multiple sectors was already in its DNA, planted through its 1930 partnership with the British South African Company, which introduced agricultural and commercial interests to present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia.

Anglo has also been dominant in South Africa’s political life, playing, for example, a crucial role in facilitating talks between the exiled ANC and the apartheid government.

All this was done with self-interest at its core, of course, and the advent of democracy presented opportunities to become a focused global miner, with a move to London after a merger with Minorco and a 1999 listing, along with South African Breweries, later SABMiller, and Old Mutual, among others.

The London listing proved to be a turning point that would see the company’s commitment to South Africa questioned and it was advised to exit the country completely to improve its risk profile with investors.

But the move to London was not its first venture abroad. In 1961, the company invested in the Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting Company in Canada and, in 1973, it opened its first office in Brazil.

It is often said that, to see the roots of a multinational, look at the dominant nationalities on its board and executive team. If you use that measure, then Anglo shed its South African roots quicker than its London-listed South African peers. It brought in non-South Africans such as Sir Mark Moody-Stuart as chairperson from 2001 to 2009 and, in 2005, René Médori as financial director — he is due to retire at the end of this year. The Anglo board currently features a single South African, former Sasol executive Nolitha Fakude.

Anglo never imagined that the new South Africa it helped to bring about would turn out to be such a challenging place to do business — not just in terms of mining but also in its clashes with the government.

The most contentious of the many fights has been over its empowerment status. Anglo has always argued that its empowerment contribution should be measured in the entities it has helped to create, starting with the 1994 sale of Johnnic and JCI to the National Empowerment Consortium and the African Mining Group.

Anglo, perhaps correctly, wants to be credited with its sales of mining assets that have helped to create African Rainbow Minerals, Exxaro and, more recently, Mike Teke’s Seriti Resources. Anglo also relies on company-level partnerships such as those between Patrice Motsepe and Royal Bafokeng Holdings for its platinum assets to count towards empowerment ownership.

But even if one takes these two categories into account, Anglo still has to do a deal at group level. There may be no black investors capable of purchasing a stake (reportedly R32‑billion) in the company like Indian billionaire Anil Agarwal recently did. Those who can, like Motsepe, would rather have their own investment vehicles.

But Anglo can assemble a broad-based consortium and use vendor financing and funders such as the Public Investment Corporation. Can it sell 30%? Probably not, but even 5% would be a start.

In fact, Anglo’s three-pronged birthday gift to South Africa should include announcing its most comprehensive social spending programme to date through its chairperson’s fund, established in 1974 but now outsourced, partly in response to the #FeesMustFall crisis and other social challenges. It should also deepen its entrepreneurship drive with more investment in Zimele, its enterprise development vehicle, and should offer shares to the public, including to black South Africans.

The most courageous thing Anglo has done in democratic South Africa was its decision, in 2002, to offer free antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to its HIV-positive workers. This was in the face of dithering government policy while then-president Thabo Mbeki flirted with dissident science and stalled the public rollout of the life-saving drugs. Anglo’s groundbreaking step led to big business changing the way it viewed and managed HIV in the workplace and, in 2008, the company extended its ARV programme to its workers’ families.

And then, of course, there was the 2004 fight with chief executive Tony Trahar over his comments to the Financial Times that there was some “political risk” in South Africa. This came soon after companies such as Sasol, in their filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States, had listed black economic empowerment as a risk.

Mbeki blew his top, questioning whether Trahar was suggesting that there was more risk then than during apartheid. Yet some of those risk factors, such as social instability as a result of high unemployment and fights over ownership of land, have lingered or even worsened. It would be interesting to hear what Mbeki makes of political risk now.

In 2009, Anglo was faced with calls by the ANC to appoint a black chairperson, specifically Cyril Ramaphosa. Anglo resisted the pressure and proceeded to appoint Sir John Parker, who is now coming to the end of his tenure. Anglo’s diplomatic public resistance must have been accompanied by private laughter as it saw right through the ANC’s cynical lobbying.

In much the same way as the ANC does not want a female president but rather a female president it can control, so too did the ANC not want a black Anglo chairperson but rather one it felt it could control — in Ramaphosa’s case, to tap him to pay for party conferences and birthday parties and to line up his ANC comrades when the expected asset sale took place.

For one, the ANC had not checked whether Ramaphosa’s mining interests in Shanduka would be a conflict of interest. And, if they were honest about wanting a black chairperson, there were more suitable candidates, such as Fred Phaswana, who had extensive board experience and had chaired Anglo Platinum and BP.

As Anglo celebrates it can happily declare: “We are still standing.” In the years that it has been in London, none of what was predicted has come to pass. When many thought Anglo might shift its primary listing back to Johannesburg because of political pressure, it stood firm. That issue is now more applicable to Old Mutual, with calls to return its domicile to South Africa, because the country remains a major profit centre.

Those who also thought that Anglo would abandon South Africa before anyone else have been proven wrong, with Gold Fields and BHP Billiton ditching the country first with the creation of Sibanye Gold and South32, respectively. The talk that Anglo would be bought by a larger rival has not come to pass — not yet, anyway — yet SABMiller, perceived as more stable, has been bought out.

Here’s to the next 100 years.