Every Women silk tapestry.

The Joburg Art Fair sort of prepared us for Instagram. The visual overload of imagery during its inaugural opening in 2008, where Robin Rhode was the featured artist, was a novel sensation. The temporary white cubes demarcating gallery stands in the Sandton Convention Centre were heaving with art. Hanging work salon style was the rage in that first and subsequent years — until gallerists figured that less translates into more sales.

In the decade that this annual art event has existed much has changed: the art, the prices, the galleries and how Artlogic, the founder and organiser of the art fair, have confronted and displaced the event’s commercial function and advanced its “Africanness”. In other respects, such as the ownership of the art industry, the profile of the gatekeepers and how art is valued, nothing has changed.

Most importantly, the fair altered the way we look at art — or don’t look at it, as the case may be. Perhaps not even during the Johannesburg biennales of the late 1990s had so much visual expression been packed into one space. In your first round of the fair on the opening night, you invariably surrender to it being a social event, opting to air kiss instead of scrutinising art.

When visitors leaned in closely to an artwork it was not to study a mark or brushstroke but to see what had seemingly been treated as top secret for so long; the price. It wasn’t quite like the #GuptaLeaks. The truth was sometimes less ugly than you had imagined.

This set a tone that shaped exchanges and formal communication about the fair. Its success or effect was always measured numerically. This was one way of processing all the art — with so much on view it was tricky for commentators, curators and gallerists to extrapolate truths about visual expression. Whatever truths were laid bare, they were always commercially driven and therefore skewed. This imperative to some degree (as well as other numerous factors) fed into the major shift from a photographic-driven art discourse to a turn towards abstract art, which now dominates.

As curators Okwui Enwezor and Rory Bester would drive home in the gargantuan Rise and Fall of Apartheid exhibition in 2014, photography had played a pivotal role in the “war of aesthetics” and had social value. International interest in this aspect of our visual culture through museum shows appeared to substantiate this.

As such, all our acclaimed photo-graphers featured widely across the fair in those early years. In 2009, David Goldblatt, the Essop brothers Hasan and Husein, Jodie Bieber, Jo Ractliffe, Santu Mofokeng, Guy Tillim, Roger Ballen, Lolo Veleko and Mikhael Subotzky were the attraction. This was art that was seen as socially relevant; sales told another story. As art auction figures continue to substantiate, editioned photographs are not viewed as valuable in rands and cents.

Photographic practices in contemporary art haven’t ceased. Goldblatt was the featured artist in 2013 when Artlogic decided to claim that year as one dedicated to photography. But this was out of sync with the art that was being produced and sold. In that year, for example, Stevenson’s stand was devoted to Ian Grose’s quasi- abstract paintings, Mary Sibande presented her abstract “purple” beings and Ayanda Mabulu’s painting Yakhali’nkomo (Black Man’s Cry), featuring President Jacob Zuma crushing the head of a miner under his foot, was banned from Commune 1’s stand until Goldblatt removed his art in protest.

Political or social truths probably could no longer be told with photographs. Ed Young, the rising art fair darling (or enfant terrible to some) was turning heads with slogans and true-to-life sculptures. Commenting on the hyper-commercialisation of art, the pressure on artists to make art-fair art, in 2012 he produced the infamous My Gallerist Made Me Do It. It featured a small, life-like replica of Young hanging from a nail.

The “war of aesthetics”, as Enwezor had dubbed it, had shifted in the post-truth era.

For several years after the inaugural fair, Artlogic would make a big deal about the figures, the turn-over and the number of visitors. According to their website, last year R43-million worth of art was sold. With FNB as the sponsor, no doubt they were forced to speak that language and substantiate art’s fiscal value as a way to quantify its effect.

The fair itself could be viewed as the barometer of change in the arts, because it has evolved in its decade- long lifespan.

The change of leadership of Artlogic in itself tells a tale of transformation. It has gone from being a largely parochial event steered by a bullish and, at times, conceited white male, Ross Douglas, who relocated to France to pursue running other expos (soon after the embarrassing censorship debacle with the Mabulu work), to one run by white women.

Cobi Labuschagne, Douglas’s business partner who had been in the shadows initially, stepped into the limelight when, in 2014, curator Lucy MacGarry was appointed. Today Artlogic is a black-dominated team headed by Mandla Sibeko who was introduced to the public when Douglas stepped away from his active involvement, but appears to have only stepped up to the podium since MacGarry’s exit. He owns shares in Artlogic, though they are mum on his actual stake and he is the only black shareholder in the business.

Many of the galleries that participated in the first fairs are no longer in business — Rooke and AOP galleries — or have become committed dealers, jettisoning the gallery space — such as the João Ferreira Gallery, Warren Siebrits, Erdmann Contemporary, Afronova and Seippel. The commercial art galleries are predominately white male-owned. More white women have pushed their way into the industry — there are three more female-run local galleries and there are a number of male-female teams too.

Of the 28 participating this year it appears from a quick head-count that only five are black-owned. The majority of galleries are South African.

This has ramifications for a fair that has always prided itself on being representative of the “contemporary African art” on the continent. Douglas touted this slogan from the beginning. He may have been ahead of his time. He knew African contemporary art would have currency in a hungry global art market, constantly on the search for the “new”. But he did not know how to deliver on this. There weren’t enough thriving commercial galleries on the continent and so he inevitably accepted those specialising in this “genre” based in Western centres, leaving the fair as one that gave a view of the African contemporary through a Eurocentric lens.

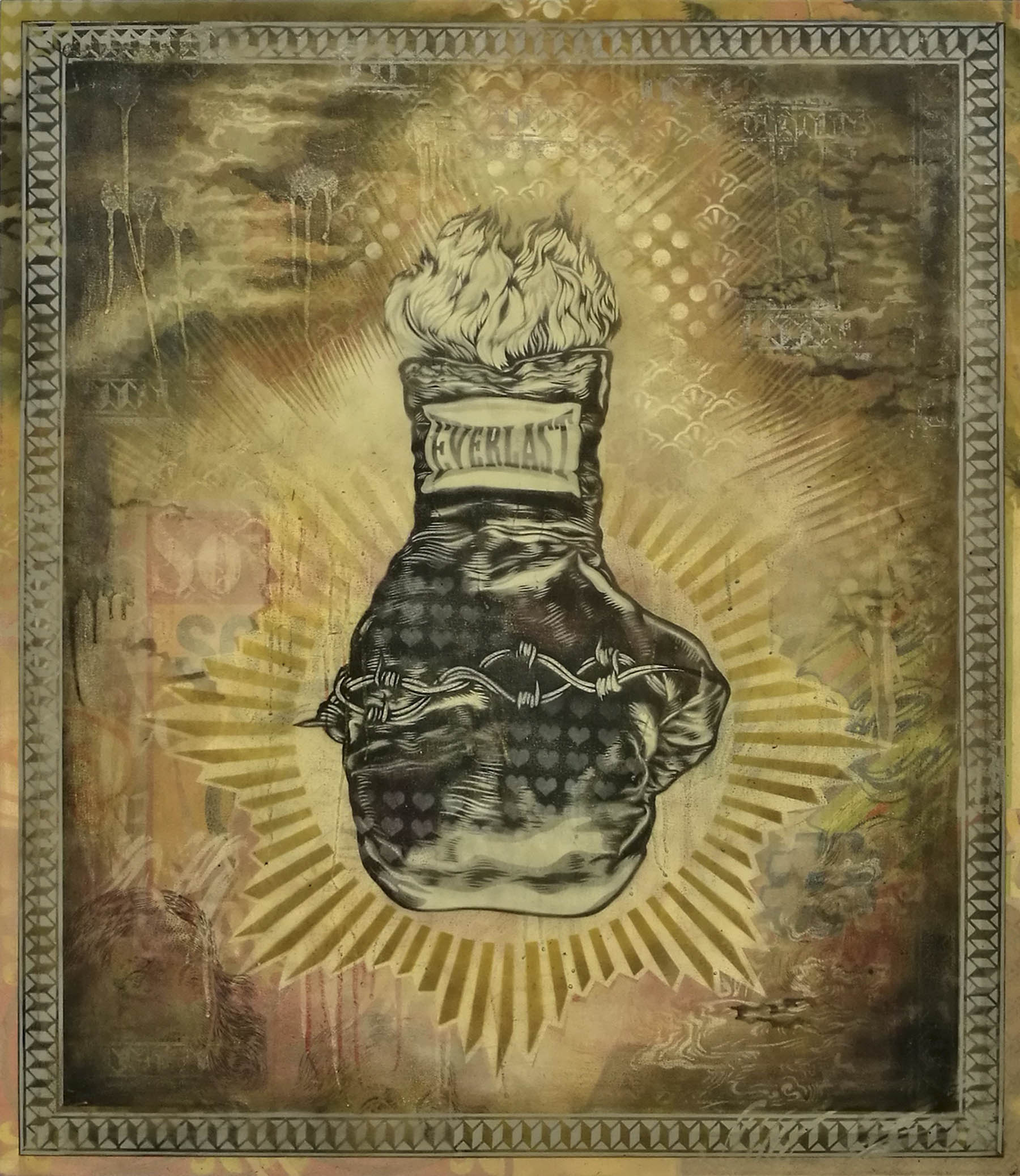

[At the art fair this year Khaya Witbooi’s Labour of Glove is amongst some of the work to be showcased]

This would conflict with Artlogic’s drive to attract buyers and curators from those centres. When the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair was established in London in 2013, before adding a New York edition, and one in Paris, dubbed the African Art Fair, the Joburg Art Fair must have struggled to attract an audience that could enjoy visual arts from the continent, when they could do so in their back garden. Not surprisingly, local and other African-based gallerists are now opting to exhibit on those platforms rather than local ones.

Nevertheless, the Joburg Art Fair has only since last year become more Afrocentric in terms of its content. The big push in this direction was heralded by MacGarry, who established an East African focus, presenting seven galleries and platforms from Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda and securing Kenyan-born Wangechi Mutu as the featured artist. The quality of the art was a little uneven and it was clear no grass-roots research was done in these countries.

Artlogic is not the only gatekeepers of this fair. Access to it and the kind of art shown in it is not in the hands of the so-called curators. In 2014 it established a selection committee (chaired by Michelle Constant each year), which MacGarry suggested was necessary to “ensure a level of quality that competes on an international level”. Artlogic doesn’t embrace much transparency about this, avoiding naming the individuals on this committee. It claims the committee revolves every two years, but many in the industry suggest the same gallerists serve on it every year, push their own agendas and limit the potential of their competitors.

This year representatives from Smac, Stevenson, Whatiftheworld and Gallery Momo are serving. These are all South African-based, large galleries. Only Gallery Momo is black-owned.

To counter the dry commercial function of the fair and to keep the “art” factor intact, noncommercial initiatives have remained a constant feature. This has most successfully manifested through filmic works. In 2008, the Swiss-born, Paris-based curator Simon Njami curated a group exhibition of video art cheekily titled As You Like It. Douglas was disappointed that none sold, but Njami viewed this as a sign of its success — he was never much of a fan of art fairs.

In 2012, there was a film installation by Bridget Baker, Only Half Taken. Mutu showed the 2013 animation The End of Eating Everything and in 2015 Candice Breitz, the Berlin-based South African, set up two booths where her seminal films charting how gender is inculcated through mass media, Him + Her, were screened. These were for sale and were rumoured to have come with a R1.6-million price tag. Inevitably, everything at the art fair becomes commodified and perhaps it should — if value in this setting translates into a price tag.

Performance art was relied upon to inject that arty je ne sais quoi. In 2012, Trade Rerouted by Nontobeko Ntombela was a highlight that responded to the fair setting. Performed by Anthea Moys and Donna Kukama with Jamie Gowrie and Shannon Ferguson, the project saw the performers making and selling rough doodles of expensive artworks.

Art fairs are strange cultural animals. They are the new “art museums”, the settings where we literally consume art. They make us aware that art and artists don’t reside on the periphery of society any longer — they are part of the same systems as everyone else.

This explains how the fair’s evolution and lack of transformation reflects broader realities beyond the Sandton Convention Centre. It is easy to think that the commercialisation of art the fair has accelerated has proved a limit for art-making. But it is also worth entertaining the notion that it has been liberating in a country where art was burdened to have the status quo changed. It has freed artists to think about art itself.

The FNB Joburg Art Fair runs from September 8 to 10 at the Sandton Convention Centre