'Since time is distance in space'

In Mame-Diarra Niang’s constructed Black Hole, there is, quite immediately, little room for journalistic subterfuge. As the realisation settles that removing shoes is a requirement for entering the space, our furtively prepared notes and questions are also gently let down, relegated to the realm of the obsolete. It is too dark to read, too black to look. But plenty to see.

A pause. Once we are inside the Black Hole (the title of her recent residency), we collectively descend on to the foam floor, where the power dynamics are destabilised and we cease to be professionals and strangers but instead become five jittery souls who all want this exchange to go well.

Three journalists, the artist and the gallery representative. The fifth floor of Stevenson Johannesburg is a fitting place for an artist like Niang. Elevated, difficult to get to without a functioning lift and perched in the darkness of the abstract — an environmental vaccine to the fever of the FNB Joburg Art Fair that was palpable in the city at the time of our interview.

Vulnerability. The feeling and the word emerge as a guide to a conversation that dislocates itself from its cerebral and intellectual territory to use emotion as a device by which the abstract nature of Niang’s latest work, the video installation Since time is distance in space, can be experienced.

The combination of the smell of burning incense and the music that accompanies the exhibition, which Niang composes from an app on an iPad that sits on her lap, creates a feeling of hyper-presence that is usually difficult to achieve when viewing art within the relentless context of the white cube in contemporary galleries.

The sense that she has prepared the space for visitors offers a respite from the monthly ritual of consuming new work within a noisy exhibition opening environment, often lubricated by wine, small talk and a nervous distance from the work on the walls. Here, presence is crucial, talking is big and there is a big bottle of still water from which we all drink with no glasses.

“The only thing that you are sure is you is your presence; it’s like your gospel,” she says early into our conversation, sitting cross-legged on the foam and enveloped by three wall-to-wall video projections. It’s too early to decipher meanings from the works on the walls but the setting curtails the doubt that abstract video work can muster in one’s sensibilities.

Niang is visibly excited to have other energies in the space. This moment is the revelation of her self-imposed banishment into her own mind since she arrived in Johannesburg from Paris, where she lives, in the middle of August. The work registers like an exploration of literal and figurative self, territory, time and space. It was conceived in Dakar a year ago and produced between there and Johannesburg, but looks like nowhere in particular — a manifestation of her preoccupation with territory.

Since time is distance in space is an altogether different notion of landscape compared with her previous photographic works At the Wall, Sahel Gris and Metropolis, which are series of photographs of nameless and sparsely populated terrestria in Africa that do not scream their location.

[An unknown location in Metropolis (Mame-Diarra Niang)]

“I erase the name of a city in my work because it’s my territory; I make it whatever I want. It’s so complicated in general to just claim this,’’ she says, speaking of her determination not to be confined. Her audacity in de-Africanising Africa’s fetishised landscape is important in understanding what she offers to the world.

In Since time is distance in space, Niang liberates time, territory and her own body from the frame and releases them into the ether, where they are comfortably lost or perhaps searching. It is unclear. She consistently considers territory and the frame in her work as liminal concepts where freedom can be found. It’s something she attributes to growing up in different places.

“My mother sent me to Ivory Coast [from Senegal] when I was one year [old], or something like that. She was sick and I lived with my grandfather and I forgot her. I forgot my first territory.”

She reclaimed it when she became an artist following the death of her father 10 years ago, prompting her reluctant return to Senegal, a country she had difficulty loving.

“This country challenged my mind because I was always hidden there. I couldn’t see them either. I realised there that I was a homosexual when I was a teenager. When I was there, it was a big box of fears. Those difficulties showed me my frame, a limit that I can push … When my father died, finally he left me the space to be. It was not any more his territory; it was mine. I started to see the landscape differently.”

That sense of finding one’s place has been an indelible part of her process of being in this research-and-making-mode while in Johannesburg. “At this moment I am quite lost,” she reveals. “I’m really looking for real conversation, a real family of thinkers,” alluding to the fact that she has felt alone in this Black Hole, the gallery and this city.

She is quite candid about her difficulties with the gallery, in a way that’s unfamiliar to we South Africans who are well trained in not calling spades what they are. There’s a dangling question floating among us hacks as we converse, that of whether the gallery has figured out how to support her as an artist whose artistic gaze is not focused on her visible identity as a mixed race woman who is a homosexual Francophone African with European blood. This in the age and cultural climate of colonial and identity excavation, of remembering and revising history.

There is a dissonance in the geographical, historical and physiological placelessness of Niang’s work and South Africa, where white-owned galleries seem to be clamouring for the work of black artists with a zeal that speaks to the changed times but also to the rapacious consumption of blackness as an ideological (and culturally lucrative) badge of honour. It’s difficult territory to traverse in a capitalist context, made more so by the subject matter in which the works of contemporary black artists are rooted in relation to the end buyer and owner.

In the current context, the artistic representation of the effects of apartheid, slavery and colonialism on people’s identities becomes displayed, collected and owned by the very same people who are the root cause of the black condition that can be summed up as black pain.

It’s something that Niang as an outsider notices and empathises with — but rejects. “Sometimes as an ‘African artist’, which I don’t want to be — I hate this frame — I really try to understand how it could be possible for you to live like that with your history. Your history is painful. I’ve never experienced something like that. I’m not sure if I could be as strong as you. It is a lot.”

That said, does she not experience this to some degree as someone who is represented by an African gallery — Stevenson — where nearly all the directors are white?

There is momentary silence as the smoke and mirrors recede in the face of contradictory truths. After all, she is in this space and wants to make it work. She does not have another gallery in Paris, an indication that her work is at odds with the gallery system in general.

“I don’t really exhibit my work. I would love to have a show but I don’t know,” she says. This is strange, coming from somebody who has created a space where so much is being found by its visitors, who are evolving in real time, imagining the aftermath of blackness and Africanness.

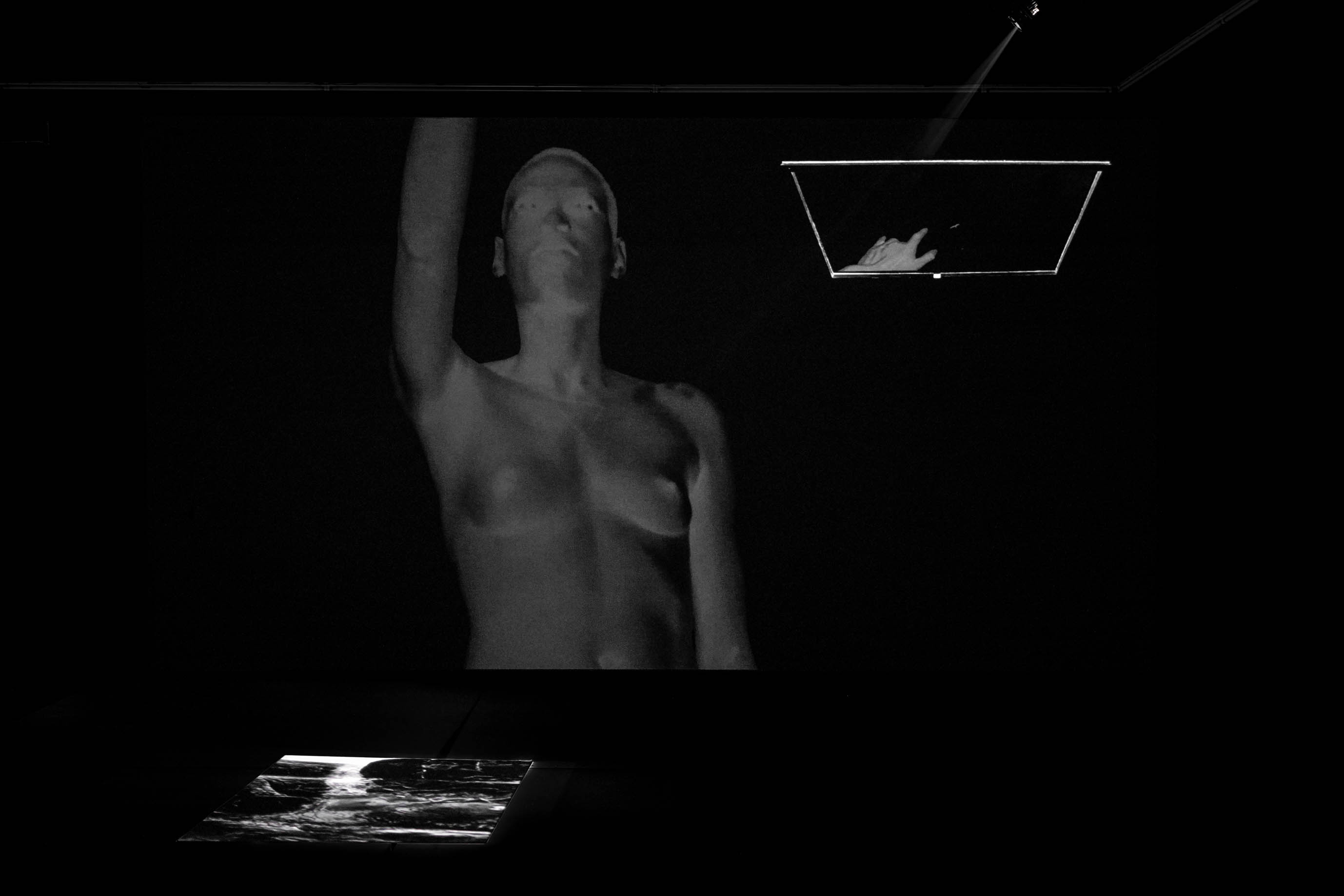

[Niang’s form, naked, colourless and floating in space (Mame-Diarra Niang/ Stevenson Gallery)]

Niang’s use of her own body in Since time is distance in space, looking like the negative of an analogue photograph, is a new exploration. She floats backwards and forwards, naked and colourless, a territory belonging everywhere and nowhere, eating time and drinking space beyond the paradigm of the visible.

We talk about souls, spirits, energies and pain as information, the prelude to her journey as an artist. “I was unveiled two years and a half ago. One day, I start to meditate and I start to see clearly things; I said: ‘Stop the bullshit now.’ I start to understand that you know in the morning when you wake up and you are in pain, you are not in a good mood … In fact, it is a warning that it is your day and you have to push your fear, go through your fear because something great will happen to you if you go through this fear.

“Before that, I was a victim of myself. When I felt these things, I would stay in and sleep, depressed and do nothing. But my magic, in fact, was behind these things. I found myself with meditation because, during meditation, I find that I have to sit on these fears and sit on this pain, which was not pain any more but information. All your pain brings messages. I mean, the universe loves you — it is not bad. You just have to receive and not be resistant. If you resist, then it’s painful.”

Through her photographs, which she has exhibited around the world and in group shows at Stevenson; and her latest work, Niang generously gives to the viewer a world beyond the visible. Suspended moments inside the imagination. Flights of freedom into the vast nature of human interiority. A gift of seeing through and beyond the visible. Which leaves us thinking about how else to be in the universe.