The various components of the books value chain — spanning writers, publishers, printers, booksellers and distributors — are having to get by using the digital sphere.

There is no watertight formula for buying books — whether it is for academic purposes, leisure reading or something in between.

Sure, you can Google “bookstore that offers African literature” or “indie bookstores in Gauteng”, as I did, and the suggestions of where to go may be helpful. But this is not to say that your literary needs will be met by where you look for what you are looking for. When this happens, it’s easy to fall into the “buy what they have available” trap.

As a keen reader with “new book money” in my pocket on a mission to shop for new African literature, I was determined to make an informed purchase.

At first the plan was to visit as many bookstores as I had mapped out to see on foot in one day. But I grew tired and so this escapade spread over a two-day period.

The first day was on foot, from Park Station in Johannesburg’s city centre, and the next day by car between Jo’burg and Pretoria.

We have our reliable evergreens —the book retailers where our parents bought our high school textbooks, the places where we swipe our loyalty cards in December when we’ve finally saved up enough money to binge on novels we had been fantasising about reading.

These are mainstream retailers such as Exclusive Books, Juta, CNA and Van Schaik. They may not always have what we want, but their lifespan must mean something to the average reader. In terms of my mission the operative phrase was “they may not always have what we want’’.

This means there is still a demand for bookstores that cater for a specific niche market. CUM books, a chain of Christian family bookshops, has exemplified this need for more than 24 years in South Africa.

In 2015, Fortescue and Nokuthula Helepi from Vanderbijlpark mirrored the idea of specialising in a specific type of literature when they opened African Flavour Books, a bookstore that specialises in African literature. Only 20% of their literary intake is by authors outside the African continent.

In an earlier interview with the Mail & Guardian, Fortescue Helepi said they did it for two reasons. The first was a response to the notion that black people are not interested in literature. “It wouldn’t be fair for the next generation to grow up believing that black people don’t read,” he said. The second had to do with having a bookstore in close proximity.

Before the Vanderbijlpark bookstore, the couple would travel for an hour to get to a bookstore — with no guarantee that they would find what they were looking for.

[African Flavour in Braamfontein (Delwyn Verasamy/ M&G)]

In September this year, a second African Flavour opened up. This time in Braamfontein, where I spent some time last Friday afternoon.

In between book recommendations, the staff — most of whom have worked in major bookstores — told me about the Helepis. “Can you believe they started out selling books from their boot?” said one employee.

The strategy of book vendors selling from their cars or suitcases to the people they come across in the streets was also the origin of Bridge Books in Jo’burg’s Commissioner Street, which Griffin Shea established in 2016.

While doing research about the book industry mainly in downtown Johannesburg, under a creative writing programme at the University of the Witwatersrand, Shea had the opportunity to interview Jacana Media’s publisher Bridget Impey.

After the interview Impey sent him away with 20 books to sell. Shea began selling his intake from a backpack but eventually they filled the boot of his car. Then Bridge Books was born.

Visiting these two stores, I notice how similar their objectives are: to fill the shortage of African literature available in South Africa. The execution, through the services provided and the layout of the stores, differentiates the two stores.

Bridge Books shelves their books backwards and places its used and new books together instead of separating them. This serves as a sort of ode to not judging a book by its cover.

At African Flavour the shelving method is conventional, in the sense that it categorises books by genre and the covers are on display but there seem to be no secondhand books.

[Bridge Books treats new and used books as equals (Delwyn Verasamy/ M&G)]

Bridge Books offers a drop-off and collection service if the customer is in close proximity; African Flavour does not have a delivery or online purchasing system in place.

Research and long walks in the city’s centre revealed that there are many more ways and places to get a book. There are the tiny indie bookstores that take up a space as small as a passage, second-hand retailers who operate on a bartering system, and underground joints that peddle counterfeit books — all of which were recommended by colleagues, friends and family.

Each bookstore has a purpose, from offering rare finds to democratising books by selling them for next to nothing.

All this is available in Johannesburg’s centre and a small part of Pretoria.

There is also the option of buying books online from the likes of takealot.com and Amazon, or as PDFs on apps such as Google Play Books. The options for ways to get hold of a book are wide and so are the models that retailers use when they set up shop. So what makes a bookstore worth going into?

I would say it is almost impossible to set up a single formula for all budding bookstore owners and those seeking to improve their spaces. And there is a pattern in what the managers and bookstore owners say — the most important thing is understanding the clientele they are serving and to adapt their bookstore model to suit them. For example, the African Flavour branch in Vanderbijlpark offers customers a lay-by option, but the one in Braamfontein has not yet seen a need for this service.

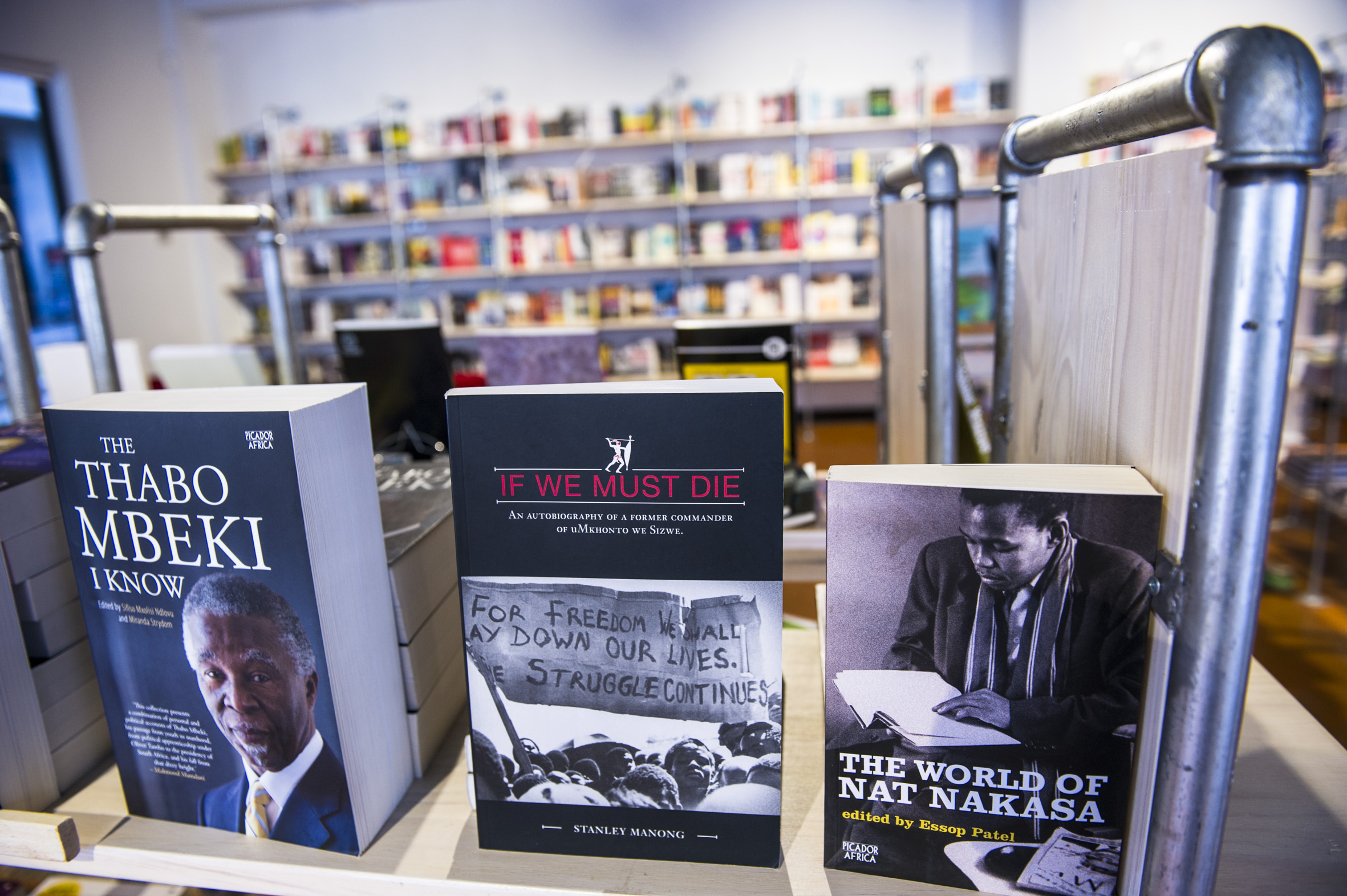

[On display at African Flavour’s new branch in Braamfontein (Delwyn Verasamy/ M&G)]

It’s hard to tell what would keep customers going back, but there are a few things that have made me plan subsequent visits.

The first is a varied price range. That way I know my chances of affording a book mid-month and just after pay day are equal. The bookstores most likely to have this element are those that sell new books alongside their identical second-hand copies. The second is the variety of books on offer and their arrangement in a comprehensible manner.

Third, it’s great to have assistance from the people who work in the bookstore, but I want the option of being able to wander around on my own and still find what I am looking for.

Then, having approachable staff, who know what they have in stock, what to recommend and whether it is possible to order a book, is a must.

Another must is breathing room in the shelves. Readers shouldn’t be overwhelmed when they browse the aisles. If I cannot afford to buy a book where the intake is small, overwhelming me with thousands of books in the same price range also does nothing for me.

The last must has to do with a bookstore’s ability to charm me with its unique personality.

The most charming are those with a backstory of how the owners worked their way towards establishing a space for the clientele they’re serving by interacting with the residents of that area. This human element allows me to connect with them because it becomes more than just about selling books. In a seemingly saturated industry, that is no longer enough.

By the end of my mission to buy a book I decided to keep the money I had planned on spending, probably because of my awareness of having so many options and wanting to explore them all.

I couldn’t decide between a stack of books for my niece, including Zukiswa Wanner’s Refilwe and selfishly filling up my library with reads such as Inyanga: Sarah Mashele’s story by Lilian Simon, The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins and whatever second-hand copy they have of something by bell hooks. Ideally, I’ll do both.

I probably need to add to my book fund before I finalise the purchases.