‘Good guys’ versus ‘bad guys’: The author maintains that unless the ANC puts the economy on a sustainable growth path and changes the current divisive narrative

The consensus among private economists is that South Africa’s overwhelming priority has to be job creation. This means that existing businesses will have to grow and invest and many more new businesses will have to be created. This can only happen in a more market-friendly environment in which there is greater policy coherence and certainty.

This means that the relationship between the government and business will have to be repaired. To quote FirstRand chairperson Laurie Dippenaar: “The country will not succeed if government is pro-growth but anti-business and simultaneously crony-capitalist.” But, above all, the government needs to rethink its statist approach to running the economy, acknowledging that it has neither the funds nor the capacity to continue down its current path.

Many of the economy’s historical growth drivers are exhausted. Unless it changes course, the country faces the prospect of long-term stagflation, with little improvement likely in per capita income growth over the next five years — and that’s if everything goes relatively well.

Should the global climate turn more hostile to emerging markets and South Africa experiences multiple sovereign-rating downgrades flowing from more populist or interventionist government policies or continued policy inertia, the country could be in real trouble.

Old Mutual Investment Group senior economist Johann Els summed up South Africa’s economic predicament: “We currently have no fundamental growth-driver, considering the lack of [any] global, sectoral, productivity or growth boom. In addition, we are facing a difficult policy environment, with monetary and fiscal policy tight and a highly uncertain regulatory environment.

“Lastly, [South Africa suffers from] a lack of global competitiveness, a private-investment strike and the fact that households are financially constrained. [State-owned enterprises] and many municipalities are also financially, managerially and operationally dysfunctional.”

The obvious solution is to invite the private sector into a partnership to revive confidence and investment. As former finance minister Pravin Gordhan explained, transformative growth should be an invitation that embraces the private sector, not a club to beat it with. It shouldn’t be obsessed with a narrow exchange of ownership that benefits a well-connected elite, but with the creation of jobs and opportunities that lift the masses out of poverty.

There is no need to abandon the Constitution or radicalise existing policy to achieve this. The National Development Plan already provides the blueprint for how to accelerate inclusive growth. What has been missing is a capable, accountable state willing to implement it.

None of this means abandoning the pursuit of equity in exchange for pure economic efficiency. Trickle-down economics died when Thomas Piketty lanced it with his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. An institutionalised system of redress will have to remain among South Africa’s priorities for decades.

The trick is to rebalance the country’s approach to transformation away from elite enrichment to growth-driven inclusion and empowerment, so that it supports rather than undermines the country’s growth prospects, explained the Centre for Development and Enterprise’s Ann Bernstein. In other words, black economic empowerment scorecards must give more credit to companies that generate jobs and support enterprise creation.

The need to change the complexion of the economy is precisely why creating more jobs has become so urgent. Faster economic growth and job creation are not ends in themselves. Combined with wholesale education reform, this is the only sustainable way to ensure that masses of people are lifted out of poverty.

Any government that succeeds Jacob Zuma’s will have to prioritise economic reforms that stand to have the biggest impact. Anticipating that the government would have to choose from a long to-do list, three national treasury economists set out to find which reforms would deliver the biggest payload in terms of growth and job creation.

In an independent, peer-reviewed working paper, they estimated what the quantitative impact on the economy would be if the most binding constraints on growth were eased. This led them to suggest what South Africa’s top five economic reforms should be. Of these five reforms, they found that just three, if combined, could increase South Africa’s growth potential to close to 8% and create almost two million more jobs.

They are: boosting skills and productivity, increasing foreign direct and domestic investment (hiking the savings rate), and slashing transport and communication costs.

Sadly, it is too late to prevent the millions of rands in investment foregone, the thousands of jobs that have been shed, or the failure of an increasing number of small businesses. In any event, what needs to be done to put the economy on a sustainable growth path is beyond the capacity of South Africa’s current administration. It requires nothing less than a total change of heart by the ANC. Unless South Africa shifts on to a path of faster, more labour-intensive growth — and is able to change the divisive narrative that is scapegoating the white population, business and capitalism — a populist disaster awaits.

It is becoming increasingly obvious that, to get the economy out of bottom gear, the ANC will have to undergo wholesale leadership renewal. The first step will be removing Zuma’s mob of thugs and economic illiterates from positions of power at the ANC’s December elective conference, from which a strong, reforming party president emerges victorious. That person is likely to be the president of the country after the 2019 national elections, or possibly even before that.

A win for the anti-Zuma faction is not impossible but it is certainly not the most likely scenario, given that Zuma’s faction (which includes the security and intelligence establishment, the revenue service, the National Prosecuting Authority, the “premier league” of provincial leaders, the ANC women’s and youth leagues, the military veterans and half of KwaZulu-Natal) appears to have the numbers on its side.

Nomura strategist Peter Attard Montalto fears that the “bad guys” may have already won, because they don’t play by the rules and so are likely to try to subvert due process in some way, whereas the “good guys” are limited to invoking the Constitution and appealing to the courts. The fear is that, by the time the good guys look up from studying the rule book, the other guys will have carried off the spoils.

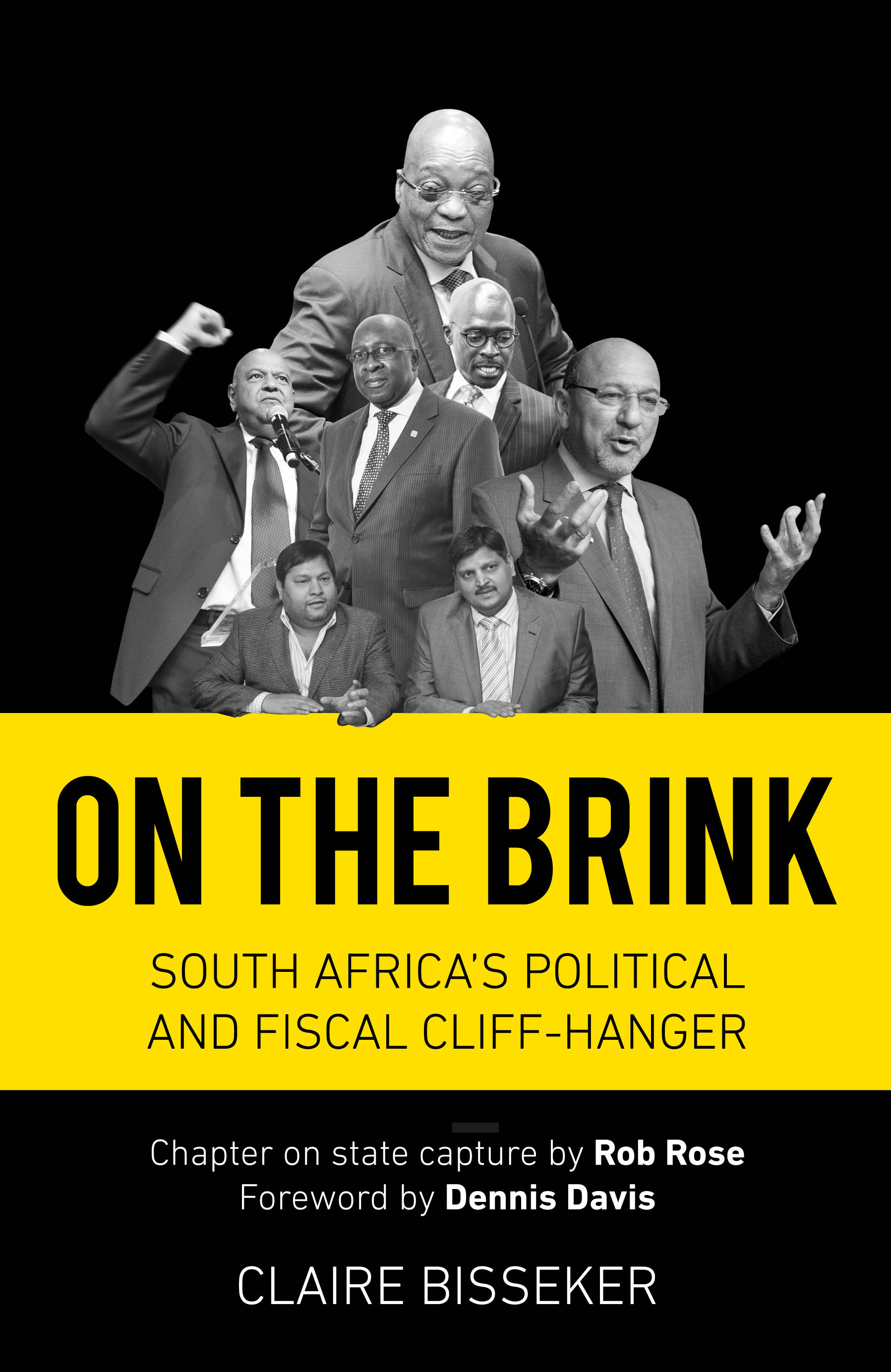

This is an edited extract from On the Brink: South Africa’s Political and Fiscal Cliffhanger, published by Tafelberg. Claire Bisseker is the economics editor of the Financial Mail