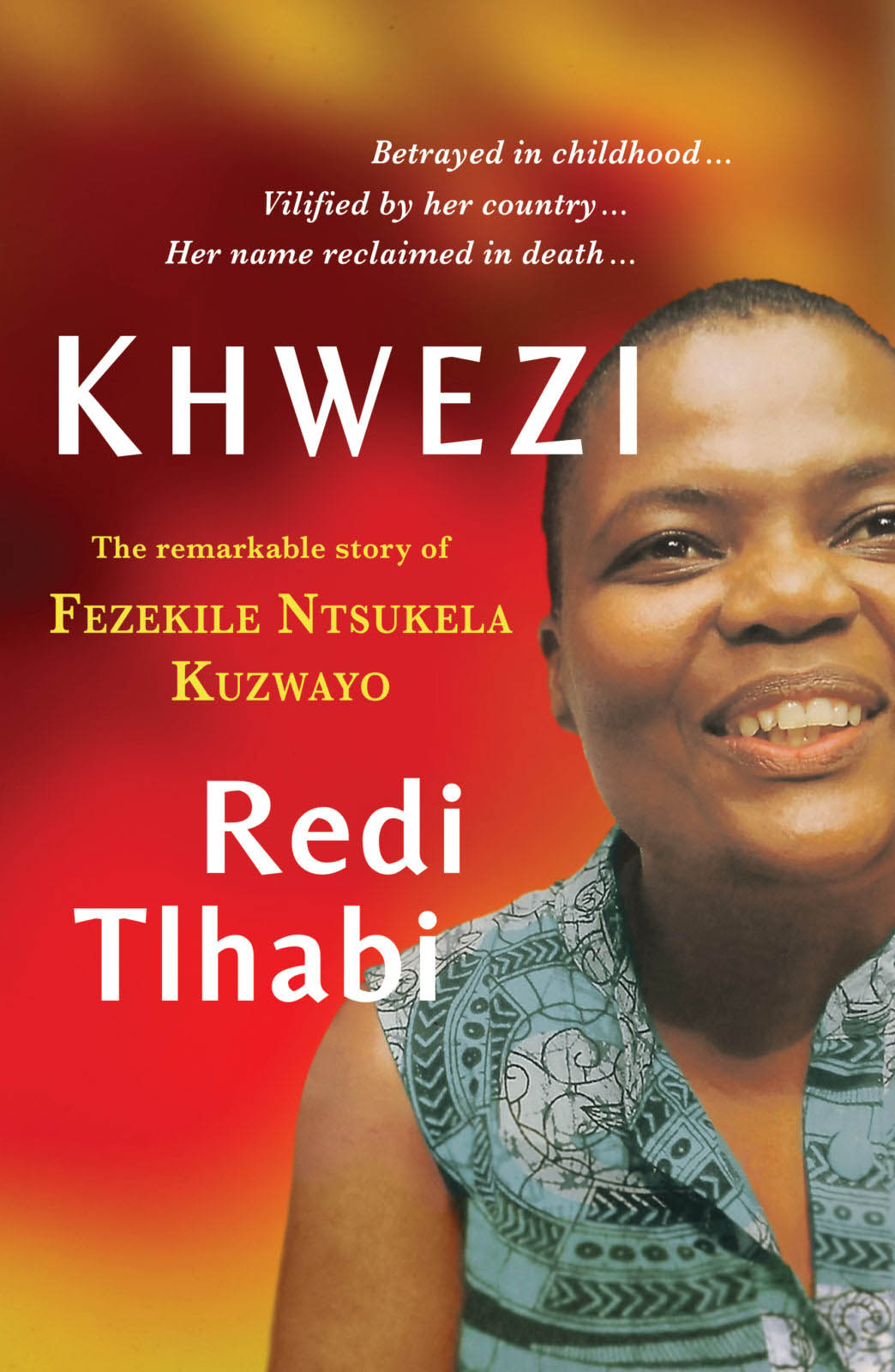

Justice denied: Redi Tlhabi's book shows how Fezekile Kuzwayo was put on trial

‘I had to fight back. I had never fought for myself. If I don’t fight back, this would keep happening to me. Even when it was clear that I would lose the case, I never once regretted fighting for myself.”

[Khwezi: The remarkable story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo (Jonathan Ball Publishers)]

This quote appears in the epilogue of Khwezi: The Remarkable Story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo. As Kuzwayo’s coffin descends into the ground, a reflective Redi Tlhabi recalls Kuzwayo’s answer to the question of “where she found the courage to lay a charge against such a powerful person”. This refers to her 2006 rape case against then deputy president Jacob Zuma.

It is a quote that is solid, succinct and somewhat indelible — a bite-sized example of how we hear Kuzwayo’s voice in the book.

During the writing of the book Kuzwayo died, making it, as Tlhabi explained in an interview with Talk Radio 702 host Eusebius McKaiser, “a very different book from what she and I had planned”.

Perhaps as a function of the practical difficulties her death presented to the completion of the book, Kuzwayo comes across to us as a series of truncated thoughts, thoughts mediated by Tlhabi. This is not necessarily a bad thing for, as its biographical scope was curtailed by death, Khwezi the book becomes about other important facets of South African public life.

Writing from the perspective of “a feminist who believed her”, Tlhabi uses Kuzwayo’s story to look at our collective complicity.

We are complicit because we forgot about Kuzwayo until we were reminded, 10 years later, of the meaning of her life by the #RememberKhwezi silent protesters at the election results centre in 2016.

We are complicit for not believing her and, instead, for perpetuating a system that in effect put her on trial for daring to challenge a man so many had backed as the future president of our country.

Tlhabi quotes Barney Mthombothi midway through the book: “We just don’t care because if we did, Zuma wouldn’t be our president.”

We are also complicit for not foregrounding issues of sexual abuse in the liberation struggle and for curtailing the avenues available to make these stories as public as those involving clear-cut political torture and assassination.

Khwezi, though it allows us hitherto unavailable access into Kuzwayo’s life, is essentially a story about how the patriarchal nature of the liberation struggle continues to be imagined. Perhaps more importantly, it is about the meaning of the trial in which she was vilified, a vilification rendered justifiable by Judge Willem van der Merwe’s verdict that found Zuma not guilty of rape.

Tlhabi takes us beyond the courtroom, asking us early on in the book to consider just how close Judson Kuzwayo (Fezekile’s father) was to Zuma. They were incarcerated together on Robben Island for 10 years for their roles as leaders of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto weSizwe (MK).

During the rape trial, Zuma went to some lengths to downplay the father-child relationship between himself and Kuzwayo, a crucial move in furthering the narrative of an existing sexual relationship with her.

As a man and a father myself, the book has added layers of meaning, forcing me to consider what the pervasiveness of male power means for our society.

What does it mean, for example, for Judson Kuzwayo to be considered an acutely disciplined senior MK commander and yet to storm off to “one of his lady friends” when a domestic quarrel raised its head? At what point do the standards we held influential men to in public begin to apply to their private lives? Sadly, in Fezekile Kuzwayo’s world it is only death that has mediated to preserve some valour in the private and public lives of the men she looked up to as father figures.

In a 2016 exchange with Tlhabi after the unveiling of a tombstone for senior MK operative Mandla Msibi, Kuzwayo recounts a conversation she had with Hlabi, one of Msibi’s children, during the rape trial. “Hlabi and I had discussed … that with Malume [Uncle] Zuma doing this, we can never know what [our fathers] might have turned out to be like. We are glad they are dead, if you know what I mean.”

To read Khwezi is to understand how, indeed, in almost all facets of our society, women remain, to paraphrase John Lennon, “the niggers of the world”.

In the chapters “Forest Town” and “On Trial”, in which Tlhabi presents the opposing accounts of the night of November 2 2005, the accused’s and the complainant’s versions are so far apart as to be irreconcilable.

But what follows — the mounting pressure from various angles, especially from women she considered mother figures — is what removes this case from the legal realm and into one that was a calculated, ruthless assault on a woman’s life.

Tlhabi does well to compress these aspects into a clear picture of how Kuzwayo buckled under this pressure, joining a police witness protection programme that was to become her psychological torture and manipulation chamber.

Sessions with her legal counsel were recorded and then used against her, and pictures of her being affectionate with police officers were taken — all with the aim of painting her as a loose woman in front of the court. The cloak-and-dagger tactics did not stop there, ably destabilising the complainant and her counsel in ways that would arguably influence the outcome of the trial.

In the flurry of those pretrial days, Zuma still had access to Kuzwayo, requesting a meeting with her “to talk about him and I”. She, in turn, asked her mother to be present at the meeting.

In the ensuing three-way meeting between Kuzwayo, her mother Beauty and Zuma, he apparently said he did not know why the incident took place.

“I imagine that this was an opportune time for Zuma to give Beauty the same reasons that he would later give the court,” Tlhabi writes, “that Fezekile ‘had consented’, ‘that their relationship was of a sexual nature’, ‘that she had come to him’ … Why could he not face Fezekile’s mother and say these things?”

Tlhabi reminds readers that, in court, Beauty and her daughter would be presented as gold-diggers for accepting education funding from the man her daughter had accused of raping her. Furthermore, by allowing Fezekile to share a bed with older male figures while she was a child — male figures who then violated this trust — Beauty was portrayed as some sort of a willing pimp of her daughter.

As a sculptor of a work of revisionism, which allows us to see the trial as essentially a travesty of justice, Tlhabi is clear cut but at the same time reluctant to get bogged down by legalese.

It is former Constitutional Court Judge Zak Yacoob who characterises the trial as a storytelling contest, with the judgment “based on which side told the better story”.

Her treatment of the president, even though the book is so damning of his conduct,

is mostly fair. The invocation of his middle name, Gedleyihlekisa (one who kills you with a smile), in relation to how he treated his accuser immediately after the sexual act, is a cringeworthy moment, one loosened of context and nuance, but it is a rare misstep. Tlhabi generally draws a neat line between her outrage over the trial and a humane courteousness for Zuma.

Much has been made of how Tlhabi’s distance from Kuzwayo led to an incomplete composite of her personality and circumstances. This might be a valid point. Although thorough research has been done here, there is an undertow of self-censorship constraining Tlhabi’s prose and just how much she can reveal about Kuzwayo, with whom she had been interacting a few months before she died.

Tlhabi is largely reverent of her subject’s complexity, leaving readers infuriated and, by turns, saddened or chuckling at Kuzwayo’s flightiness and naivety.

Her distance takes little away from the premise of the book. And so I walk away from the read able to say: Fezekile, I believe you.

Khwezi: The Remarkable Story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo by Redi Tlhabi is published by Jonathan Ball