Amandla! Ngawethu: During the #FeesMustFall protests Wits students continued the protest tradition of call and response struggle songs

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” — Thelonious Monk

This popular adage addresses the difficulty of writing about music, its importance and its role in society. One may never truly capture the essence of what a song means to different people, or where and how they choose to use it. This is made all the more difficult when songs are used by a people battling systematic oppression.

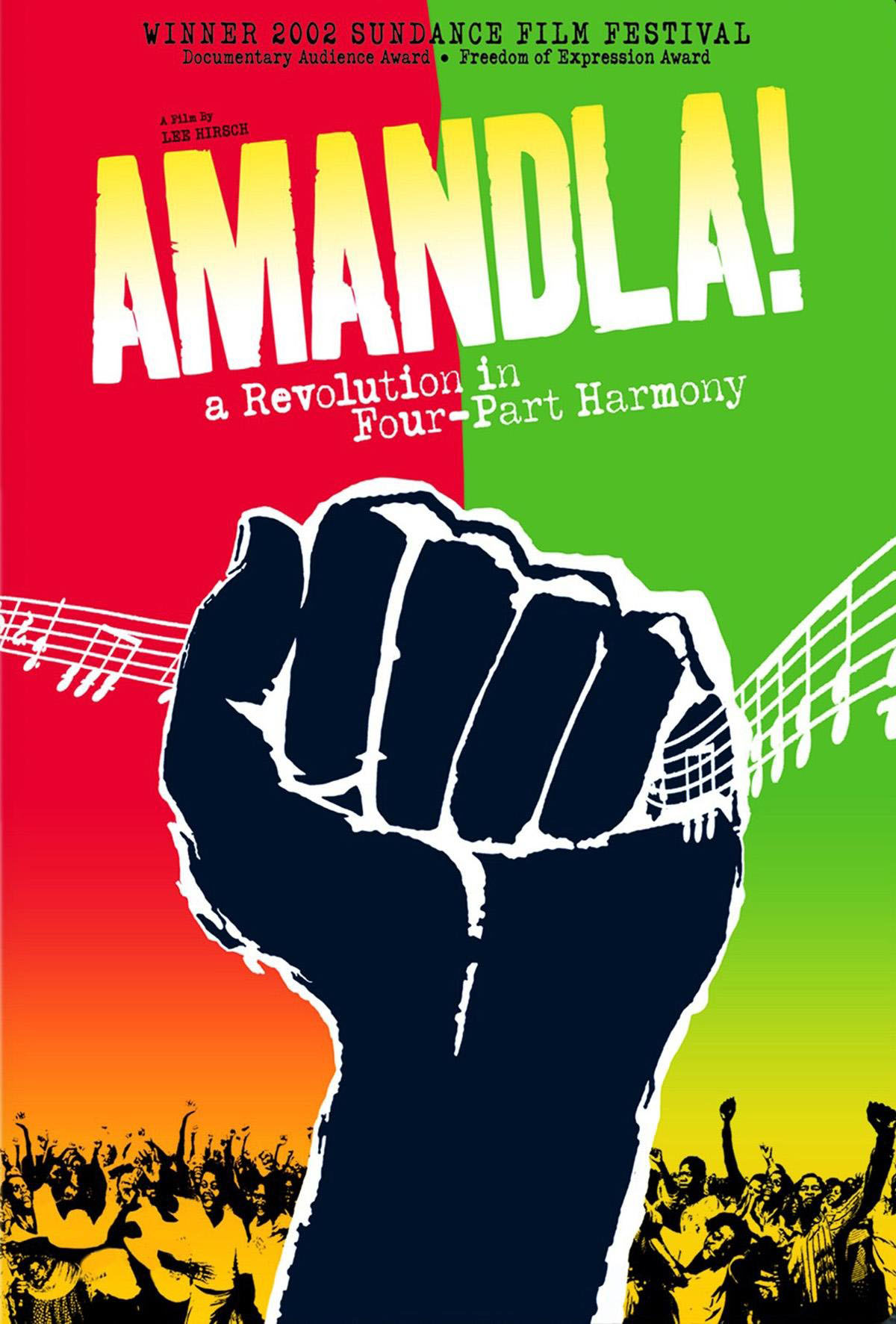

Abdullah Ibrahim, in the documentary film Amandla! A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony, speaks about how there has rarely been a liberation or protest movement that has not, at some stage, used song as a tool to rally people to its cause, keep up morale, or mourn those who have fallen or have been arrested.

[Amandla! A Revolution in Four Part Harmony 2002]

This raises the question: Why do people often resort to music or song during protests and in moments of struggle? This is one of the questions the Black Thought Symposium wanted to answer when they initiated a project called Ingoma Yomzabalazo.

A group of students, lecturers and artists at the University of the Witwatersrand established the symposium to critically explore the ideas surrounding race, politics and culture. The collective is also interested in using different kinds of aesthetics to give an account of the black experience.

The Ingoma Yomzabalazo project began at the height of the #FeesMustFall protests and aimed to spark a conversation about struggle songs and what they might mean. At its inception, the project sought to find ways to speak about how song has been used as a form of resistance.

In the collective imagination of many South Africans, songs of struggle are venerated. For many in this country, a protest without song is simply not a protest at all. It is something that South Africans seem to have internalised, and the #FeesMustFall movement was an example of this.

But what did it mean for students to sing about the debates surrounding decolonisation and transformation? Was the singing a way to heal a people who have had to endure centuries of suffering? Does this form of singing serve only to gather people under one roof, or is it just a form of disruption, as many media reports have suggested?

These are indeed difficult questions and the answers will undoubtedly differ depending on who one speaks to. Answers to these questions are further frustrated by the limited literature or work done on struggle songs and their meaning. The vague history of struggle songs and the ambiguity of their meaning shows how much work still has to be done to work through the labyrinth that is the song in struggle.

If anything has been clear about these songs, it is that they are not just about reliving our experiences, not just about nostalgia and history. Rather, they are the way we relate to ourselves as a nation. It is where we recreate and reconfigure who we are and how we want to be as a country. Struggle songs become a theatre of our desires and an arena of our fantasies.

[ANC supporters pray in front of the courthouse of Johannesburg, 28 December 1956 (Stringer/ AFP)]

Shana Redmond, in her book Anthem: Social Movements and Sounds of Solidarity in the African Diaspora, writes that struggle songs are powerful acts that compel “reactive and proactive engagements and debate” and contribute to “political alternatives in the present”.

The Ingoma Yomzabalazo project proposes alternatives and artistic interventions to the current state of affairs. It invites us to think critically about what these songs mean, and then maybe we can begin to answer the questions about what must be done to change the status quo.

Struggle songs can become a passage through which we become alive and renew. With liberation songs, people have been able to articulate views that they have rarely had the opportunity to express at conferences and in the decision-making bodies of their political parties.

Struggle songs are by far the most democratic process that exists in protest and social movements — when people sing together, the call-and-response structure of revolutionary songs allows for collective engagement.

In these situations, song exerts an extremely powerful influence on human behaviour. On purely individual and physiological levels, song can affect our heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and the chemical composition of our brains. It can hijack our internal reward system, stimulate our fight-or-flight mechanisms, and compel us to move our physical selves to the same beat.

But perhaps the most powerful aspect of liberation songs, and indeed of music more generally, is their ability to create connections between large numbers of people. Music is a temporal art form, that is to say it unfolds over time. Unlike the visual arts, music is able to structure time through rhythm and pulse, and in doing so lay the foundations for participation and collectivity.

Through song, we are able to theorise while struggling and fighting. We are able to strategise while in the picket lines. When students sang Mbobo vuleka (loosely translated “open the hole”) during the protests, everyone knew the implicit message — that people should attack or prepare to attack; no one needed to explain or dictate what should be done.

Using different songs, the protesters were able to create a language and a structured way of communication that they all understood. Furthermore, struggle songs within the #FeesMustFall movement showed how some of the hierarchies and cries of resistance that evolved out of the brutality of colonialism and apartheid still exist today.

Although new songs have been composed over the years in response to contemporary struggles, some of the songs have remained largely unchanged, deployed by a socially and politically engaged civil society to address South Africa’s post-liberation contentions.

These songs are weapons in a cultural arsenal that draws on years of resistance and determination. Cultural armament is nothing new in Southern Africa. For hundreds of years, communities have, in one way or another, resisted the imperial zeal of figures such as Cecil Rhodes and Hendrik Verwoerd, and their various attempts at the systematic erasure of local ways of being by deploying their cultures in defiance.

In each instance, the songs and dances absorbed new meanings and new associations. With each performance, whether in defiance or lamentation, an ongoing identity of struggle was being cultivated. Throughout South Africa’s liberation struggle, songs were used to unify, strengthen and engender resolve in the face of state oppression.

Song is a particularly well-suited art form for achieving such feats. Organisations and movements continue to draw from this rich repertoire of expressive culture and appropriate their powerful mobilising influences. Part of the power of struggle songs comes from the fact that they are a form of emotional self-expression that cannot be diluted or taken away, not even by the most repressive of regimes that denied black South Africans their being, or governments that promise change but deliver little more than the status quo.

The voice (and indeed the body) is an extremely powerful communicative medium. Communication does not simply occur with the use of words and phrases, but also with the channelling of emotions as expressed through song. Songs of struggle become powerful vectors of emotional potential as they become intimately intertwined in South Africa’s social and political landscape.

With each new deployment of the country’s liberation songs, their meanings evolve. Whether they are being sung at large gatherings to protest unjust laws, by Abahlali baseMjondolo demanding land and housing, or by students to demand decolonisation and transformation, these songs continue to be powerful tools with which the South African people can carve out a vision for their country.

Mbe Mbhele is a student at the University of the Witwatersrand and co-founder of the Black Thought Symposium. Gavin Robert Walker is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Africa Open-Institute for Music, Research and Innovation at Stellenbosch University