(Photo: Reuters)

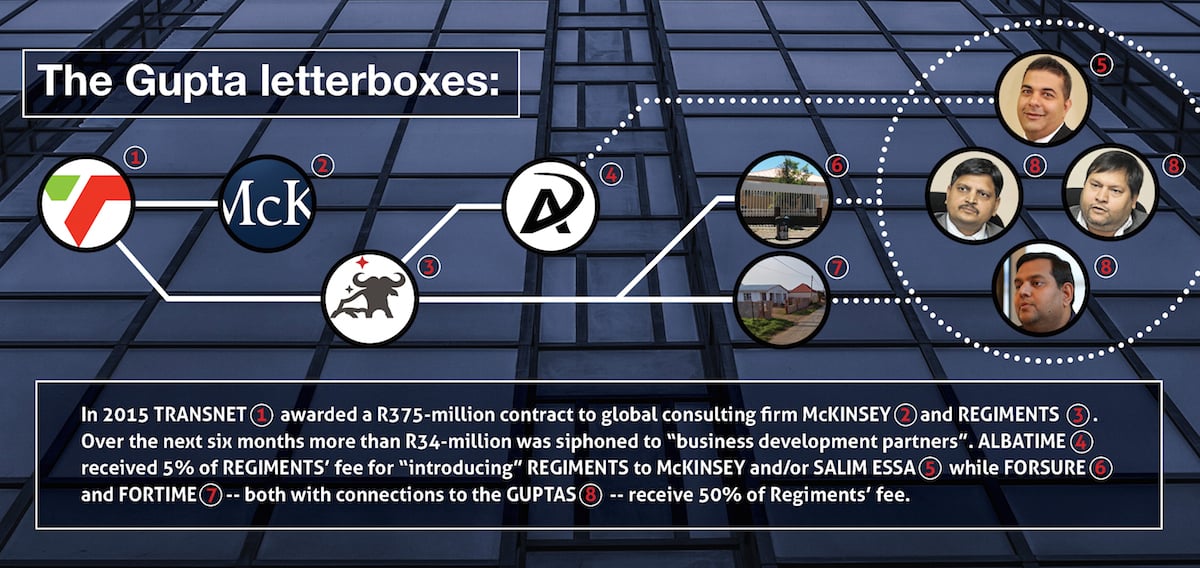

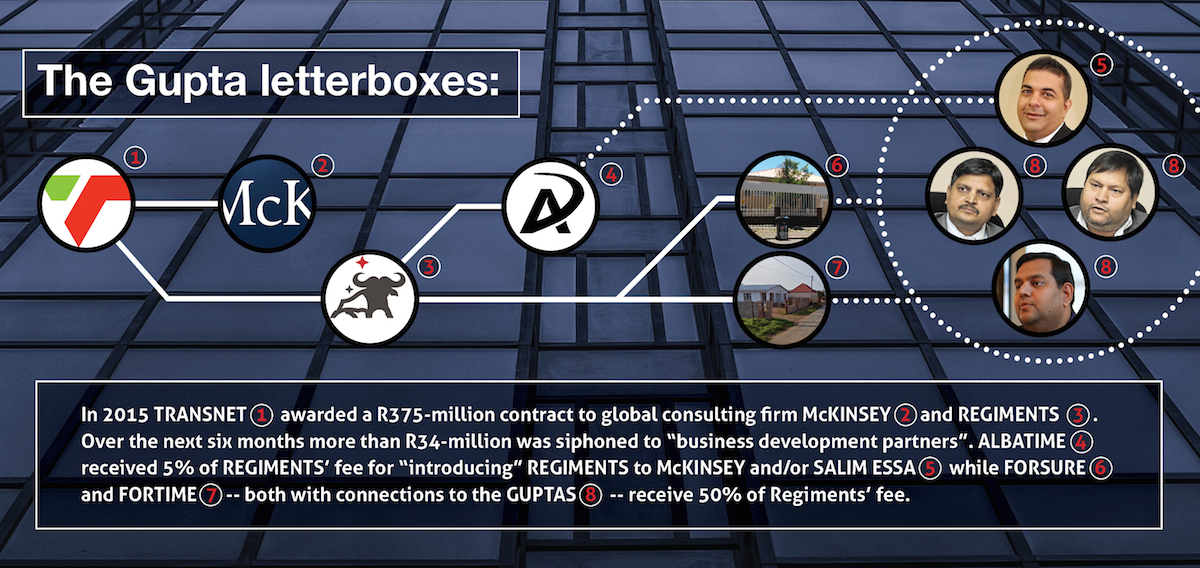

When global consulting firm McKinsey “came clean” last Tuesday about its work at Eskom, it admitted it was not careful enough about associating with Trillian, its de facto local partner. But it claimed not to have known that Gupta lieutenant Salim Essa owned most of Trillian. Now we show that at least R30-million flowed from Regiments, McKinsey’s longstanding local partner at Transnet, into companies associated with a notorious Gupta-Essa money laundering channel. McKinsey refuses to comment on the payments, styled as fees to “business development partners”. Once again, it was the major beneficiary of the resultant contracts.

amaBhungane’s Sam Sole discusses the latest McKinsey dossier revelations with the SABC’s Francis Herd

It is said that people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. But sometimes when they do we all benefit because we find out what has been going on inside for years.

Regiments Capital is situated at 35 Ferguson Road in Illovo, Johannesburg, behind an edifice of steel and glass. Four kilometres down the road at Melrose Arch, Regiments’ former colleagues and now bitter rivals, Trillian Capital Partners, set up shop in their own glass fortress.

For years, Regiments benefited from lucrative consulting and advisory contracts with state entities.

Then in 2015, Regiments director Eric Wood and Gupta lieutenant Salim Essa began building the Trillian group to rival Regiments’ competencies in financial advisory, management consulting and asset management.

When Wood formally crossed over to the new group in early 2016, he took with him half of Regiments’ staff and some of its best contracts.

“Regiments … was basically shut down in the [state-owned entity] space,” Regiments director Niven Pillay told us in a recent interview. “Post mid-2015 … we sort of understood we were not going to win any of that business any more.”

The fallout that followed, chronicled in court papers and leaked whistle-blower documents, has provided unprecedented insight into how Regiments became the partner of choice for international consulting firm McKinsey on big Transnet contracts.

There is mounting evidence that Regiments’ success was partly based on the payment of very large “commissions”.

The company’s internal documents suggest it paid over as much as 55% of its contract income to facilitators, including to letterbox companies connected to Essa and the Guptas.

“The Regiments relationship was a bone of contention with many partners at McKinsey,” a former McKinsey consultant told amaBhungane. “People kept asking, ‘Why are we working with these people?’ The feeling was if we want to do the work [at Transnet] this is the cost.”

The size of the payments and their ultimate destination suggest they were kickbacks in all but name – though the questions about who knew about them, who approved them and who received them remain bitterly contested.

Regiments’ two remaining directors have claimed they only discovered the payments after Wood left the firm and said they hired forensic investigators to determine who received the more than R30-million and why. Wood disputes this, saying all three of them signed off on all the payments.

Over two months, amaBhungane has sent six requests to McKinsey asking whether it was aware of the lavish fees Regiments paid to various “business development partners”.

McKinsey dodged the question each time.

However, there is more at stake for McKinsey than for its local partners.

On Thursday, the Financial Times reported that US authorities were investigating the #GuptaLeaks, including illicit commissions laundered to Gupta associates in the United States. Corruption Watch has said it will ask the US department of justice to expand its probe to include McKinsey.

McKinsey has denied knowing Trillian was controlled by Essa or that by partnering with Trillian it was becoming a participant in a multibillion-rand State Capture play.

In its “coming clean” statement last Tuesday, it said: “We believe that Trillian withheld information from us about its connections to a Gupta family associate.”

However, under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, US companies can still be prosecuted for being “wilfully blind” to corruption.

If McKinsey knew that Regiments was siphoning large fees to politically connected facilitators – including allegedly to Essa – it would be difficult to believe that McKinsey accidentally signed up for the same deal with Trillian.

R375-million train to nowhere

In 2015, Transnet had a problem. Spurred on by advice from McKinsey, it had committed to spending R50-billion on 1,064 new locomotives to meet what was forecast to be a rapidly growing demand for freight rail.

But the demand did not materialise and Transnet found itself splurging cash on engines it did not need.

Transnet’s solution was the R375-million “general freight business Breakthrough” consulting project.

Awarded to Regiments and McKinsey in 2015, the aim was to increase Transnet’s general freight business (GFB), which hauls anything from grain to manganese, from 90.6 to 106 million tonnes a year.

A memo authored by Wood and McKinsey partner Vikas Sagar equated the project to “ambitious plans … to ensure the affordability of [Transnet’s] capital investment programme”, including the 1,064 locomotives.

Court papers that Wood filed after his breakup with Regiments show that Regiments and McKinsey stood to make R155-million in fixed fees and another R220-million in potential “success” fees.

Technically, Regiments would take the lead but the fees would be split 50:50.

A spreadsheet shows that over 10 months Regiments diverted an astonishing 55% of its proceeds from Transnet to “business development partners”.

The spreadsheet, which contains Regiments’ general ledger for the GFB project, forms part of a trove of information disclosed by Bianca Goodson, a whistle-blower who earlier headed a Trillian division.

In fact, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that “business development” fees of 50% or more were standard practice for Regiments.

Mr Five Percent

There are not many public photos of Kuben Moodley – one of the few shows him with his arm around President Jacob Zuma.

Moodley earlier acted as an adviser to Gupta-linked mines’ minister Mosebenzi Zwane but he more commonly acts as an agent, helping companies to secure deals.

Wood said in court papers filed in November 2016: “Moodley operates inter alia as a ‘facilitator’ of commercial transactions. When Mr Moodley came across possible opportunities in the market, he would bring them to Regiments. If Regiments took up the opportunities, Mr Moodley would be remunerated through a ‘finder’s fee’.”

At first blush, it would seem the claim is that Moodley was paid for introducing Regiments to McKinsey.

In our interview, Pillay said: “[Moodley’s company] Albatime … took us into a relationship with McKinsey and got paid a commission for that… Like an estate agent might introduce a buyer to a property and then gets a commission from the seller, Albatime got a commission… Anything that came via the McKinsey relationship, we shared five percent with Albatime.”

But Moodley denies he had a direct line to McKinsey. Rather, both he and Wood say his connection was with Essa who, as we shall see, appears to have been the real rainmaker for Regiments.

McKinsey has refused to say who made its introduction to Regiments and has repeatedly refused to answer questions about Moodley and Albatime other than to say that McKinsey itself did not pay them.

McKinsey denied contact with Essa too.

“We have… found no evidence whatsoever that McKinsey had any dealings with Salim Essa in connection with Regiments, or with Transnet or any other client,” it told amaBhungane.

Goodson’s spreadsheet suggests that between May 2015 and January 2016, Albatime received R3.1-million excluding VAT in “business development” fees from Regiments, but stood to earn triple that amount over the entire 18-month contract. Whether that happened, we do not know.

The contradictions multiply

Regiments’ Pillay insisted that Moodley was paid for introducing Regiments to McKinsey and no one else. Asked if Moodley acted as a facilitator on other projects, he said: “No, only on McKinsey.”

Yet, a Transnet pension fund alleges in recent court papers that Regiments paid R50.7-million to Moodley and Albatime between December 2015 and April 2016 for providing “business development” services on a Transnet contract that had nothing to do with McKinsey.

“I don’t have any record of that… This is the first I’m hearing of that,” Pillay told amaBhungane, though he admitted being aware of the court matter.

Wood is emphatic that Moodley and Albatime’s 5% “finder’s fee”, rather than for a direct introduction to McKinsey, involved bringing in Essa.

“Mr Kuben Moodley is a personal friend of [Regiments’] Mr Niven Pillay,” Trillian said in a statement on behalf of Wood.

“Mr Pillay entered into an arrangement with Mr Moodley and his company Albatime whereby Albatime would assist in Regiments’ business development. To this end, Mr Moodley introduced Mr Essa to Mr Pillay in 2012.”

Moodley initially skirted questions about the services he provided to Regiments, instead saying in a written response: “Albatime reiterates that any money received by it from Regiments Capital was pursuant to a contract between Albatime and Regiments Capital and was paid against valid invoices.”

However, Moodley followed up his written statement with two angry calls to amaBhungane.

Asked about Pillay’s claim that he was paid for introducing Regiments to McKinsey, Moodley said: “I don’t know McKinsey, motherfucker. I know Salim Essa… I introduced – in 2012 – Salim Essa to Niven Pillay…

“Niven is trying to get away from the fact that I introduced him to Salim Essa… He’s trying to save his own ass. I don’t know for what because we’ve done nothing wrong. We did the work, we got the business, what the fuck!”

Chicks, alcohol, clothes

Asked what “business development” services actually entailed, Moodley cited an example of an IT company flying executives to a luxury golf estate for a weekend that included “free clothes, free food, free plane tickets” and “alcohol … as much as you want”.

“That’s called business development,” Moodley said, then cited another example of a company that flies businessmen and politicians to Zimbali luxury resort outside Durban for a weekend: “Paid for – chicks, alcohol, clothes, whatever. You know what that’s called? It’s called business development… When a black person does business development it’s called corruption.”

Moodley would not say how “business development” services squared with laws designed to prevent public servants from being influenced by exactly these types of overtures, but said: “I’ve done nothing wrong. I did business development… I worked to get business in.

“That’s what Albatime does. Obviously Albatime has been closed down because you fucked my whole life up… I’ve got no money. I’ve got nothing left. I’ve spent it all on lawyers because of you c**ts.”

Mr 50 Percent?

Moodley did not elaborate on how an introduction to Essa would translate into increased business for Regiments. However, Essa previously facilitated access to a separate, very large Transnet contract under the guise of business development.

amaBhungane previously reported that Hong Kong-based Tequesta Group, fronted by Essa, signed a “business development services” agreement with China South Rail (CSR) to help it win the largest part of the 1,064 locomotive tender.

The details of the arrangement leave no doubt that the fees were kickbacks. This includes Tequesta’s staggering R5.3-billion fee, and that the agreement showed CSR to be interested less in the vaguely defined “services” Tequesta was to perform than simply to get the Transnet deal.

The #GuptaLeaks show some of CSR’s money flowing to Gupta fronts in the United Arab Emirates.

It is widely rumoured that Essa played this same role for Regiments. Two well-placed sources spanning the Regiments-Trillian divide allege that Essa received a substantial percentage of Regiments’ fees for helping it get contracts from state entities, particularly at Transnet and Eskom, whose boards and senior management had been packed with Gupta associates.

Neither Essa nor the Guptas responded to emailed questions.

The total paid to “business development partners” was 55%. Five percent, Goodson’s spreadsheet shows, went to Moodley’s Albatime.

The rest – an astounding 50% of Regiments’ Transnet fee – went to two altogether more opaque companies, Forsure and Fortime.

In other words, for every R200 Transnet disbursed on the project, McKinsey and Regiments each separately received R100. However, out of the R100 Regiments got, R55 was immediately transferred to the “business development partners” – R5 to Moodley’s Albatime and R50 to either Forsure or Fortime.

Over the time of Goodson’s spreadsheet data, Forsure, Fortime and other unnamed “business development” partners appear to have received a total of R31.5-million on top of Albatime’s R3.1-million. Both figures exclude VAT.

The context leaves little doubt Forsure and Fortime were fronts for Essa and the Guptas.

Forsure has a clear link to a letterbox company previously identified as a front for Gupta kickbacks: Homix.

The Yellow House

The house at 103 St Fillans Avenue in Mayfair, Johannesburg, is worlds apart from Regiments’ glass tower in Illovo.

amaBhungane has visited the modest yellow house many times since 2015 trying to find further traces of Homix, which was registered to this address.

Homix was paid R76-million in kickbacks by telecommunications company Neotel, which had won two large Transnet contracts. Its connection to the Guptas was first exposed when Ashok Narayan, formerly a Gupta executive, came forward to identify himself as Homix’s “chief executive” after Neotel’s auditors raised concerns.

Although the Guptas claimed at the time that Narayan no longer worked for them, the #GuptaLeaks now show that he remained an agent of the Guptas and Essa. And according to Goodson, the Trillian whistle-blower, he was also involved in day-to-day activities at Trillian.

However, 103 St Fillans is not only the registered address of Homix, but also of another company called Forsure Consultants. Both companies also shared the same sole director, Taufique Hasware.

Forsure Consultants and the Forsure in Goodson’s spreadsheet appear to be one and the same.

The spreadsheet suggests that Forsure got 50% of everything Regiments earned from the Transnet GFB contract between May and July 2015 – R7.4-million excluding VAT in total.

Despite these riches, amaBhungane found no trace of Forsure at 103 St Fillans or at a rundown block of flats in Durban that the company’s new director, one Wassim Essop, listed as his home address.

Numerous calls to known numbers of Essop and Hasware went unanswered. A former employer said Hasware had “gone back to India”.

Relocating to Mthatha

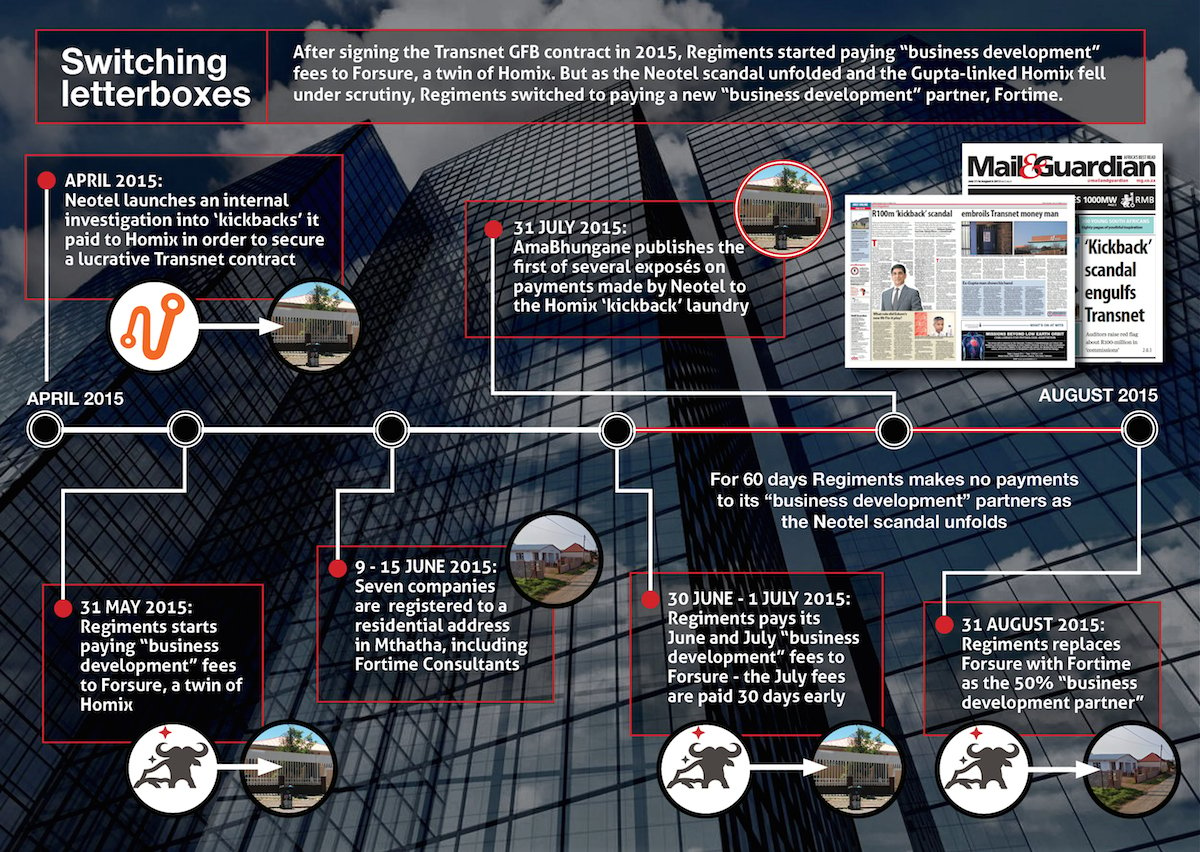

But Forsure’s usefulness as a letterbox for questionable payments appears to have been cut short alongside that of Homix.

By June 2015, both Neotel’s auditors and amaBhungane were asking questions about Homix and its role seemingly as a conduit for kickbacks to the Guptas.

Over the final weekend straddling the last day of June and first day of July, Regiments paid Forsure R5.8-million – June and July’s “business development” fees. (Incidentally, the #GuptaLeaks show that that same weekend, R1.3-million flowed to Forsure from Global Softech Solutions, a company that the Guptas were buying.)

The general ledger shows that for the next 60 days Regiments made no payments to any of the business development partners on the Transnet GFB contract.

This coincided with the Neotel kickback scandal spilling into the open as amaBhungane published a series of exposés: “ Kickback’ scandal engulfs Transnet” , “Transnet scandal: Ex-Gupta man shows his hand” and “Transnet ‘kickback’ scandal widens”.

Then on 31 August 2015, Fortime neatly took Forsure’s place as recipient of the 50% “business development” fees.

Fortime Consultants was one of seven companies registered a few months earlier to a residential address in Mthatha.

From the context, there is again little doubt that this is the same Fortime referred to in Goodson’s spreadsheet. ( From the #GuptaLeaks we know, for example, that another of the seven companies, Birsaa Projects, got R3.4-million from a Gupta-linked deals with software multinational SAP in 2016.)

As with Forsure directors Hasware and Essop, all attempts to trace the seven companies’ sole director, Ahmed Sabbir Ahmed, were unsuccessful.

Goodson’s spreadsheet ends in January 2016, by which time Regiments appears to have paid Fortime R24.1-million excluding VAT which is merely accounted for in the ledger as payments to “business development” partners.

Regiments saw no evil

In total over nine months, of the R63-million Regiments got from Transnet, it paid on R34.6-million to “business development partners”: R3.1-million to Moodley’s Albatime and R31.5-million to Forsure, Fortime and other opaque “business development” partners.

The spreadsheet shows that the payments effectively wiped out any profit Regiments would have made.

It is hard see how Regiments could ever justify cutting so much meat out of a contract, again suggesting the fees were no more than kickbacks to a grouping – the Guptas and Essa – who had the power to influence contract awards at the state rail company.

Wood denied that there was anything untoward. “Any business development fees that were paid were paid for services rendered by business development partners… [Y]our media outlet has not reported fairly in this regard.”

He would not, however, elaborate on what services the “business development partners” actually provided.

Pillay confirmed that Regiments made payments to Forsure and Fortime but said he and his fellow remaining Regiments director, Litha Nyhonyha, only found out about the payments “after the fact”.

This is not the first time Regiments’ directors have claimed to be unaware that millions of rand had flowed from their company to Gupta-linked letterboxes.

As we previously reported, leaked financial records showed that Regiments and Albatime had made payments to Homix – in Regiments’ case a whopping R84.4-million in late 2014 and early 2015.

Moodley last year said amaBhungane’s “version of events” – of these payments being kickbacks – was “so far removed from the commercial reality of the transaction that … I am not able to meaningfully comment”.

But he added: “Regiments was engaged to conduct some work for [German crane manufacturer] Liebherr and … Homix played nothing more than a business development role [our emphasis] for which it was paid a fee by agreement with Regiments Capital.”

If Liebherr sounds familiar it is because the #GuptaLeaks have also uncovered how R55-million in “commissions” was paid directly by Liebherr to Gupta front companies offshore, seemingly again to secure Transnet work.

In our recent interview, Pillay would only say that neither he nor Nyhonyha, his fellow director, “were party to any of the payments to Homix”.

Regiments promised to provide further detail on the payments to Homix, Forsure and Fortime after the company had spoken to its lawyers.

But in a final written response, Regiments would only say: “Our attorneys have [en]listed professional forensic services to get to the bottom of all these issues. That complex and cumbersome assignment is still ongoing.

“In the meantime, we have also implemented extensive governance measures around contracting and payment… We cannot comment on your questions … until the above-mentioned internal investigations are complete.”

Regiments has been keen to push a narrative of Wood as a rogue director who took decisions without his fellow directors’ knowledge.

Pillay told us: “Forsure and Fortime… I only found out about after Eric [Wood] was gone… Did they supply resources? Did they add any value? I don’t know.”

Wood, however, says that Regiments’ protestations of ignorance are completely implausible.

“All agreements and contractual relationships between Regiments and its partners were agreed to by all three principals of Regiments, i.e. Wood, Pillay and Nyhonyha,” Wood told us via Trillian.

“All payment requisitions had to be signed off by two of the three principals… [A]ll three had direct knowledge of all of the in and out flows of funds that took place at Regiments.”

Wood said the “business development” agreements were reviewed by all three directors.

One set of documents Wood filed in the court battle with Regiments appears to support his claim.

Emails and attached tables, prepared by Regiments’ chief investment officer and copied to Pillay and Nyhonyha, indicated that every public sector contract Regiments received came with business development fees of between 50 and 55% – 50% on Eskom and Denel contracts, and 55% at Transnet and South African Airways.

Of each of the deals that Regiments was pursuing with state entities at the beginning of 2016 Wood’s tables earmarked up to 55% of Regiments’ portion of the fees, R173.4-million, for unnamed business development partners.

Regiments responded saying that our interpretation of the document “is completely out of sync with reality … The document had nothing to do with actual business development partners or percentage commission.

“It was merely a template to guide the valuation discussion in order to effect the Wood separation. When it was prepared, no one at Regiments had any detailed understanding of projects, fees, business development partners and commission of the business of Trillian.”

McKinsey heard no evil

Which leaves the question of whether McKinsey – which worked alongside Regiments for years and for at least 10 months on the Transnet GFB contract – was really in the dark about the “commissions” Regiments was paying to secure work.

Wood’s tables show that the deals Regiments was pursuing in early 2016 include six with McKinsey, worth an estimate R551-million. Each of these came with potential “business development” commitments of between 50 and 55% of Regiments’ portion of the fees.

Despite amaBhungane sending six requests to McKinsey over the past two months, the US-based consulting firm has refused to say whether it knew about the huge fees its partner was paying.

There is a least one clue suggesting that McKinsey was not completely ignorant.

A joint progress report delivered by Regiments and McKinsey to Transnet in early March 2016 details how R39.9-million of the contract would be “subcontracted to B-BBEE facilitators” by Regiments.

We asked Regiments, Wood, McKinsey and Transnet to identify the B-BBEE facilitator referred to in the progress report.

Regiments could not, Wood would not, and McKinsey dodged our questions. Transnet initially said: “We are not aware of the companies that are cited as part Regiments’ supplier development programme,” but later sent a second response denying it received the progress report in question.

Regiments’ ‘political exposure’

By February 2016, it was clear that the Transnet GFB project would be an abject failure – instead of a 17% increase, volumes were expected to fall from 90.6 to just 84-million tonnes by June 2016.

And by this point McKinsey also wanted out of its partnership with Regiments.

On 23 February 2016, just 10 months into the 18-month project, McKinsey wrote to Transnet saying that it wished to cut ties with Regiments, citing “political exposure and under-delivery by Regiments”.

McKinsey declined to provide any detail on why Regiments – a company it had worked with for years and which had passed a due diligence – suddenly put them at risk of “political exposure”.

Pillay said McKinsey’s concerns were never shared with Regiments, and showed us a copy of McKinsey’s termination letter, written three weeks later, in which McKinsey said the “relationship has run its natural course” in part because the Transnet GFB contract was in the process of being ceded to Trillian.

McKinsey has not explained how Trillian, its proposed supplier development partner for a multibillion-rand project at Eskom, represented a lesser political risk, given that it was born out of Regiments.

By the end of March, McKinsey notified Eskom that it could no longer work with Trillian because it had failed its due diligence, and it withdrew from the GFB project at Transnet.

By November 2016, when Transnet terminated the contract, it had paid a total of R187-million to Regiments, McKinsey and Trillian.

In its “coming clean” statement last Tuesday, McKinsey said: “There are things we wish we had done differently and will do differently in the future, but we reject the notion that our firm was involved in any acts of bribery or corruption related to our work at Eskom and our interaction with Regiments or Trillian.”

McKinsey added that it “never served the Gupta family nor any companies publicly linked to the Gupta family.”

McKinsey appears to be desperate that this be the end of the story. But with rocks still flying between Regiments’ and Trillian’s glass houses, there is a very real risk that one of them could end up shattering McKinsey’s reputation too.

- The SABC interview with amaBhungane’s Sam Sole was added after the article was published.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Know more? Send us a tip-off.