Jürgen Schadeberg

“I did some research about African photographers but it was rather dispiriting. It seemed there were none … Finally, I discovered that the Bantu World used some freelance black photographers, but after meeting with them I remained disheartened. They knew very little about photography and expressed no interest in working for Drum.

“The trouble was that the few Africans I had met who were interested in photography had never had the chance to study it or work somewhere as trainees. There were no books on photography or photo magazines … It was true that some of the photo laboratories, of which there were few, had black technicians on their staff, but their experience was limited to making up chemicals, drying prints, dispatching them and general cleaning. They certainly did not know photography.”— Jürgen Schadeberg, The Way I See It: A Memoir

Jürgen Schadeberg’s new memoir shines light on photography as a troubled inheritance in South Africa. Max Oxley from worldphotography.org called him the “father of South African photography” and, if this is true, The Way I See It gives partial vision and writes Schadeberg into a dark place in photography, where black photographers were invisible to the European gaze and where that same gaze was fixed on native subjects in anthropological photographs to prove racist science.

This is why the history of Drum magazine matters. For this we have Schadeberg to thank, because he saved this historic archive from oblivion. Today, the history of Drum is a pivotal point for African social history and black photography in the 20th century. It counters the dominant history of the medium on the continent, which was fixated on tribe and biology at the time. Schadeberg helped to make the visual argument that blacks were not inferior to Europeans.

[The Jazzomolos in 1953 (Jürgen Schadeberg)]

But for 469 pages, The Way I See It misunderstands the history of African photography because Schadeberg, like a photographer, sees through only one eye, partially blind to where he stood relative to his black colleagues.

Regarding his time at Drum, the book does little to complicate his biography as a European photographer living and working in an apartheid city — Johannesburg — during the 1950s. What did it mean for his photography to enjoy privileged access and possess the means to travel?

Schadeberg’s claim that the African photographers he encountered “certainly did not know photography” confuses photography with photojournalism. In fact, African photographers worked in diverse ways.

Although much work still needs to go into excavating this field, we can speculate that African photographers were often itinerant or working for the administration; some worked for presses run by the missionaries or for other black-owned presses.

Then there were multiracial camera clubs out of which came photographers like Ranjith Kally (1925-2017). There were entrepreneurs like Ronald Ngilima (1914-1960), typically kept out of the city centres, who ran his family photography business in Benoni. Then there were black technicians who became internationally recognised photographers, like Ernest Cole (1940-1990) and Santu Mofokeng. Historic black women photographers from that era are yet to emerge.

The Way I See It has the potential to make it seem as though there was no African photography before the advent of Drum, and that is not true. What is true is that Schadeberg did not exist as a photojournalist before he came to South Africa from Germany and started working for Drum.

Drum was one of Africa’s earliest black lifestyle publications, which was also produced and read in Nigeria, Ghana and in other parts of West, Central and East Africa. Schadeberg started there as a photojournalist in 1951, just before the magazine came under the ownership of Jim Bailey and the editorship of Anthony Sampson. Schadeberg was responsible for Drum’s “magazine production, schedules, layouts and picture editing”.

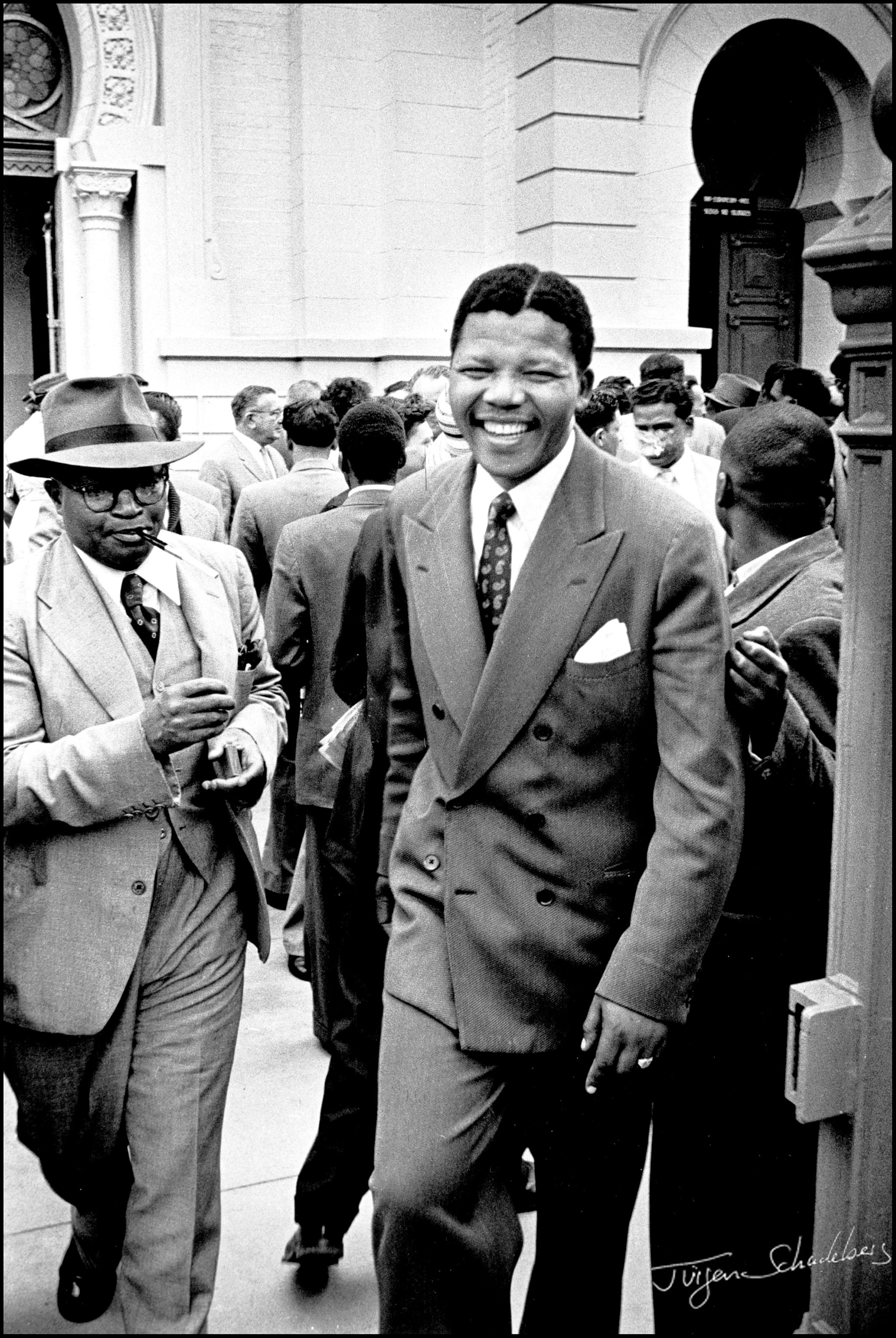

He was also its chief photographer in Johannesburg, where he photographed some of the country’s defining moments and figures like Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Alfred Xuma, Yusuf Cachalia, Ruth First, the Defiance Campaign, the Sharpeville massacre funeral and the Sophiatown removals.

[Nelson Mandela at his 1958 treason trial (Jürgen Schadeberg)]

He also staged iconic photographs with some of the culture makers of the time who surrounded him, like Dorothy Masuka, Can Themba, Es’kia “Zeke” Mphahlele, Arthur Maimane, Bloke Modisane and Casey Motsisi. The Way I See It tells of Schadeberg’s experiences making these iconic images and lets us in on the secrets behind pictures like Dolly Rathebe’s portrait on the “beach” and Miriam Makeba’s portrait at the microphone.

The Way I See It is decorated with the names of prominent black intellectuals and activists, artists, writers and politicians who posed for him. This makes Schadeberg a historic photographer whose book is important for the medium because photographers’ biographies are almost nonexistent here.

But the trouble with Schadeberg’s iconic status and with his photographs of icons-in-the-making is that it also gives his life story and his Drum photographs the dangerous tendency of standing in for history itself.

Schadeberg once sighed in an interview about “being typecast as a Drum photographer”. After eight years at the magazine, he left in 1959 and set out for new frontiers after establishing himself as a freelancer. That same year, Schadeberg read of a University of the Witwatersrand “expedition” to the Kalahari, led by Phillip Tobias (1925-2012). Schadeberg had recently discovered an interest in the San, so he decided to join Tobias and travel to his research site located 900km from Johannesburg in a place called Ghanzi, in the middle of the Kalahari desert.

Schadeberg writes that “different members of the expedition team had different tasks. Some were charged with weighing the San, some with taking measurements of their skulls, jaws, teeth and noses. Tobias and one of his female colleagues took one of the San girls into the bushes to measure her genitals. Another activity was to give them a tray filled with sand and ask them to draw various objects presented to them.”

[Schadeberg captured moments such as Hans Prignitz’s handstand atop a Hamburg church in 1948 (Jürgen Schadeberg)]

The Way I See It makes little distinction between what Schadeberg bore witness to as a photojournalist of urban African life in Johannesburg and what he saw in his encounter with the Kalahari San, who were used as primitive subjects of research.

These complexities are kept outside the book, which should be read like any photograph, keeping in mind what is shown and also asking about what is not shown, like Schadeberg’s images from his 1959 expedition, which are not published in the book.

The trouble with The Way I See It is that it tends both to conceal and reveal. The book requires the reader to look outside its pages for the vulnerabilities of Schadeberg’s career and its risks to his reputation, for instance, given the recent insights into scientists like Tobias.

Christa Kuljian’s 2016 book Darwin’s Hunch: Science, Race and the Search for Human Origins (Jacana) suggests that, as early as the 1930s, photography stood alongside the taking of face masks as a recording method in physical anthropology.

Kuljian’s book lifts the veil on the history of accepted research practices conducted by Tobias, who described San people as “living fossils”. He also “argued that physical anthropologists in South Africa did not contribute to the racist policies of apartheid”. His research is said to have furthered the study of human biology, but it also meant the erasure of San life histories.

Photography was complicit in this enterprise. The photographs of L Schultze, L Fourie, AM Cronin and MC Burkitt, published in Isaac Schapera’s The Khoisan Peoples of South Africa: Bushmen and Hottentots (1930), are typical examples of photo studies that are often the only visual record of these people’s existence in Southern Africa.

Eight years before Schapera’s book was published, Australian anatomist Raymond Dart (1893-1988) arrived in Johannesburg to lead the anatomy department at the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School, and he began conducting expeditions to the Kalahari. According to Wits historian Bruce Murray, Dart’s research has been credited with helping to build the university’s global reputation for “comparing the anatomy of different racial groups, and for bringing the search for human origins to Africa”.

Tobias succeeded Dart as the head of the anatomy department in 1959 and undertook his expedition to Ghanzi with his research team. One year later, “a woman reporter” wrote an account of her trip with Tobias in an article for Panorama magazine, published by the apartheid-era information service. The article, headlined “University team with Bushmen of Kalahari”, does not mention that Tobias measured San girls’ labia, nor that Schadeberg took photographs.

Yet the article is illustrated with a set of uncredited photographs that observe San subjects being assessed and their bodies measured, and of scientists camping in the bush and conducting these primitive tests.

The article begins with the line: “Jürgen, look, there’s something in the road”, and is followed by a photo essay of images of San people dancing around a fire at night that resemble those in Schadeberg’s 1982 book Kalahari Bushmen Dance.

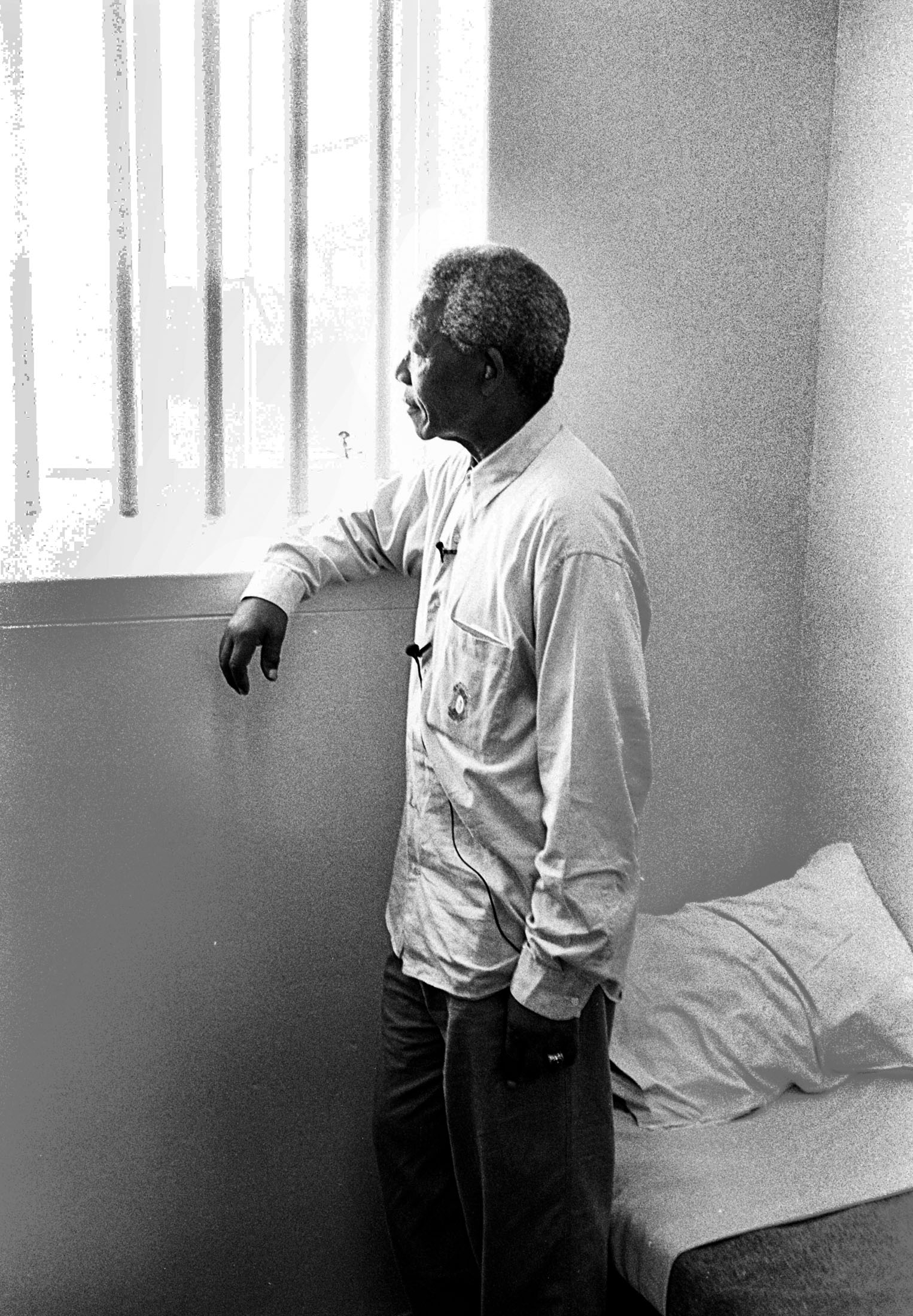

[A pensive Nelson Mandela in his Robben Island cell in 1994. (Jürgen Schadeberg)]

He got into trouble for this book, which he has chosen not to include in the list of his publications that appears on his website. The Way I See It reveals that Schadeberg doctored these images, altering the appearance of the small white identity discs that were assigned to the San who participated in Tobias’s study. The discs were attached to leather straps and were worn like necklaces that marked participants as coded specimens. Schadeberg had retouched the discs to look like shells, because he thought they were “distracting for my pictures”.

The Way I See It is a brave book, revealing much about the practice of photography. Schadeberg should also be commended for returning to South Africa in 1982 to claim back the negatives he had left behind in 1964, for taking credit for his Drum photographs, and for defending their authorship in his name.

He did what more South African photographers of his generation should do. But what does his entitlement mean for black photography’s struggles with the question of visibility? Were Schadeberg’s efforts to seek justice purely self-interested? Why does The Way I See It not reflect on the current predicament of the Drum archive, which claims to be “a people’s archive”, yet it costs R95 an hour to access the physical collection?

The Drum photo collection forms part of the Bailey’s African History Archive. The archive today holds material from Drum dating from 1951 to 1984, including items published in its Anglophone African counterparts. It also includes material from four local sister publications: the Golden City Post, Trust, True Love and City Press.

The Drum photo collection is largely populated by anonymously authored photographs. Most of the photographers whose images are in the collection have not been identified, which means that their images circulate in books, films and exhibitions like stock photographs. They serve to ensure the visibility of this historic brand, but simultaneously reinforce the invisibility of its lesser-known photographers, who are mostly black.

Schadeberg is part of the archive’s origin story. In The Way I See It, he writes about how he discovered the Drum archive in chaos and neglect, kept in a “dilapidated farmhouse” on Bailey’s estate. By then, Bailey had sold the magazine to Naspers.

“I showed him what I had found and what I was going to take,” Schadeberg writes after finding his Drum negatives and squaring this with Bailey.

The newly retrieved negatives immediately put Schadeberg to work on a dummy for a photo book. It drew little interest from the publishers he targeted in London and Amsterdam, despite their active anti-apartheid movements, but a chance encounter with Bailey on Chelsea Bridge in London changed all that. Schadeberg showed him the dummy and Bailey invited him back to South Africa to “sort out the archives”.

The Way I See It describes Schadeberg’s laborious, yearlong efforts to build the “newly organised archive” that spawned his curatorial output of the 1980s and 1990s. During that time he published books, made films and wrote a few failed movie scripts that reinvented him as a curator.

The trouble with Schadeberg’s reinvention is that, through Drum photography, it also reinvented South African 1950s history before the end of apartheid. South Africans were still fighting for freedom when his 1987 book The Finest Photos from the Old Drum was published. It predated Beyond the Barricades: Popular Resistance in South Africa (1989), published by anti-apartheid collective Afrapix and featuring the work of 21 South African photographers.

The Way I See It makes no mention of these historic moments in photography that provided the photographic context for his curatorship. This neglect is symptomatic of the book’s failure to admit that Schadeberg’s ability to look back (then and now) when the country looks forward is a responsibility best left for those invested in the outcome.

So, believe the title. The Way I See It is the only way Schadeberg sees himself and the country that invented him.