Leading the way: Mineral Affairs Minister Susan Shabangu

As a parking novice in Cape Town, I was astonished by the R132 invoice that awaited me when I returned to the car I had left in front of Parliament some hours earlier.

I was more surprised, however, by the parking marshal, who saw my treasury-branded nametag and wanted details on Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba’s medium-term budget policy statement. “Did he say he is going to fix SAA?” he asked as he processed my card payment. “Yes. kind of,” I replied. “But did he say he is going to stop giving them money? Did he say it like that?”

Alas, Gigaba did not say it like that. He expressed the government’s frustration over poorly managed state entities coming cap in hand to the treasury, and said it needed to stop. But he also said SAA would get another R4.8-billion, on top of the R5.2-billion it had received in recent months.

Evidently, talk is cheap and contingent liabilities are not.

The treasury’s fiscal risk statement, which last year was an additional handout handed out to the media, is now a nine-page annexure to the policy statement document.

In it, the treasury maps out risks to the fiscus. From further ratings downgrades to spikes in inflation, higher-than-anticipated public service wage settlements and weak financial management in municipalities — there are many things that could throw the tightly balanced budget out of kilter.

But the contingent liabilities involving the state-owned companies pose one of the biggest threats to the budget and the country as a whole.

A contingent liability is a potential liability that could occur because of a future event. The government’s major explicit contingent liabilities are its guarantees, the treasury said.

Its total guarantees issued are R688-billion, but its total guarantee exposure is R445‑billion, because several entities have not fully used their available guarantee facilities.

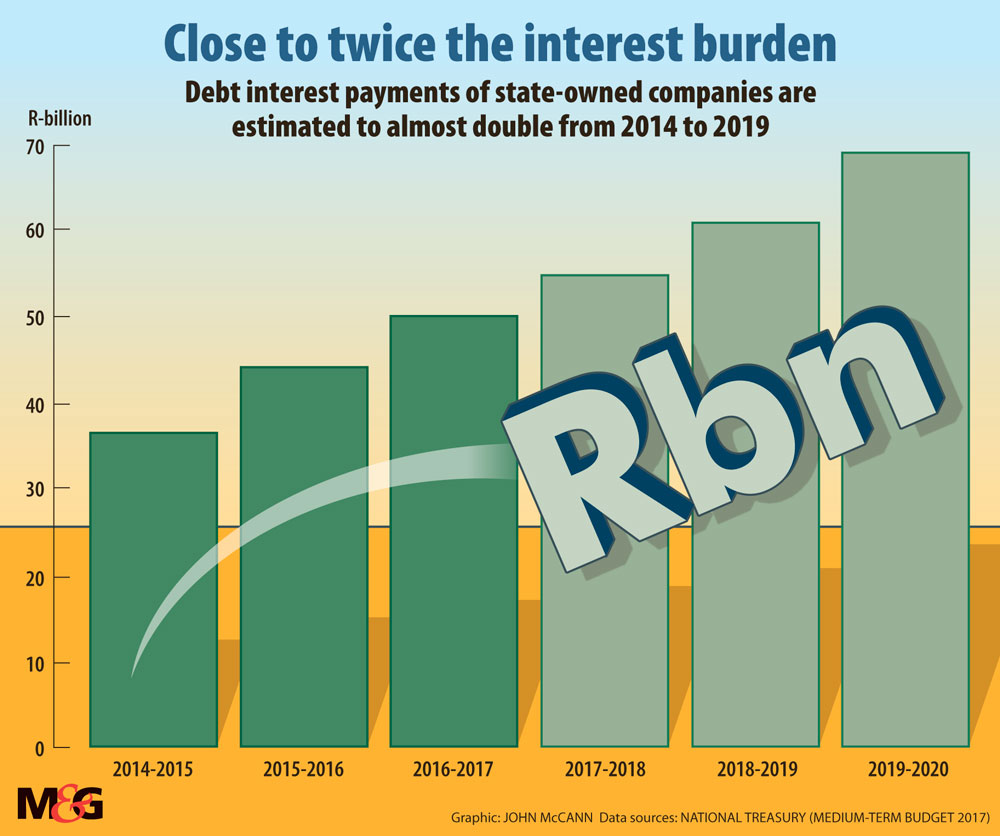

Also, state-owned companies are not faring well when measured by profitability, dropping from a 7.5% return on equity in 2011-2012 to 0.2% in 2016-2017.

“Lenders, alarmed by governance failures, are taking a more active stance,” the treasury said in the statement. “As a result, state-owned companies are having difficulty raising debt, or are forced to refinance debt at higher rates.”

In the case of the embattled SAA, lenders refused to roll over their debt, forcing the government to inject R5.2‑billion, largely to prevent SAA from defaulting. Another R4.8‑billion will be transferred to the airline by March 31 next year.

On Wednesday, the carrier said 60% will be used to pay local lenders partially and the remainder will be used as working capital. It said it is committed to a turnaround, noting the appointment of critical personnel, including the recent replacement of the airline’s discredited chairperson, Dudu Myeni.

But even after the capital allocation, the government’s exposure to SAA’s debt is significant at R15‑billion. “There is a risk that if SAA’s financial fortunes do not improve, there will be further calls on the remaining guarantee,” it said.

But by far the most worrisome contingent liability listed in the treasury’s fiscal risk statement is too-big-to-fail Eskom. The utility holds the largest state guarantee — R350‑billion — to support its capital investment programme. It has been plagued by weak governance, leading to a qualified audit opinion and a violation of some debt covenants with lenders. Eskom is at risk if the National Energy Regulator (Nersa) doesn’t grant the tariff hikes the utility has applied for and electricity sales growth underperforms.

“Any of the options required to stabilise Eskom could have significant fiscal implications,” the treasury said. High tariffs that slow economic activity could negatively affect tax collections but, if Eskom does not secure a tariff increase that is sufficient and its financial position weakens, it will seek government assistance.

Speaking to media before delivering his speech in Parliament on Wednesday, Gigaba said the budget was unable to bail out the likes of Eskom.

The Mail & Guardian reported earlier this year that, if Eskom failed financially, South Africa might have to seek financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund.

It is hoped that Nersa’s decision will put Eskom in a better position and that governance concerns will be addressed.

Other contingent liabilities on the list include:

- The South African National Roads Agency Limited was given a R38.9‑billion guarantee to expand its toll roads portfolio. This included the Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project, a controversial e-tolling project that has met with marked resistance from the politically sceptical and financially stretched public. Collections are lower than projected, making it difficult for the agency to service its debt. “Over the long term, an improvement in toll revenue collection is needed to ensure Sanral’s sustainability,” the treasury said, adding that if tolling is not used to fund major freeways, there will have to be difficult trade-offs to avoid the deterioration of the national road network.

- Arms manufacturer Denel faces refinancing and risks defaulting on government-guaranteed debt of R1.85-billion. Denel has struggled to refinance debt because of concerns about corporate governance failures and corruption. The government has extended its guarantee to the end of September next year. The treasury noted that Denel has made some strides: it has abandoned the Denel Asia Joint Venture, which it entered into with the Gupta-linked VR Laser Asia, and it has withdrawn a related court case it launched against the treasury and the minister of finance.

- The government has issued a R25.7‑billion guarantee to the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority. The agency relies on the department of water and sanitation’s water trading account to settle obligations with lenders. But the department’s poor financial management is threatening the agency’s ability to meet its commitments and raises the likelihood of a call on the guarantee. In the long term, the government’s ability to deliver water infrastructure could be compromised, the treasury said.

- The Road Accident Fund has been insolvent for more than 35 years and its total liabilities continue to grow to unsustainable levels. “An immediate concern is claim amounts that have been settled in court but not yet paid,” the treasury said. “These amounted to about R8.5‑billion at the end of 2016-2017 and are forecast to grow over the medium term.” A replacement scheme is in the works that will significantly reduce costs but it will not reduce the accumulated liability of the fund.

The fiscal risk statement also notes long-term funding commitments. Regardless of what form new policy initiatives take, the treasury expects that tertiary education will require more funding in the future as the call for free higher education persists.

Public health spend in general is anticipated to grow as a share of gross domestic product but, with the adoption of National Health Insurance, public health spending is expected to increase significantly — to 6.8% of GDP by 2025-2026.

Social grants, it is projected, will support 23.5‑million recipients by 2030-2031 and the cost that year will account for at least 3.5% of GDP.

Long-term funding has also been committed to bolster the defence force, which has deteriorated severely because of a lack of funding over the years. The recommendations of a 2015 document, the Defence Review, if implemented in full, would add R53‑billion to defence expenditure over the next six years.