(Graphic: John McCann)

NEWS ANALYSIS

Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba’s maiden budget speech was ripe with agricultural references about how South Africa must sow the seeds to eventually enjoy the harvest. But the medium-term budget policy statement was scant on who will be sowing what and when.

While he was reiterating his policy statement platitudes about how all stakeholders need to roll up their sleeves and get to planting, during a breakfast hosted by Independent Media’s Business Report at the swanky Mount Nelson Hotel on Thursday morning, the rand continued to weaken and the government’s borrowing costs continued to climb.

On Wednesday morning, the rand was at 13.70 to the dollar and, as Gigaba delivered his speech, it went past 14. By Thursday morning, it had reached 14.23 — its highest level since November last year.

If former finance minister Pravin Gordhan was the minister who could calm the markets, Gigaba seems to be the one who can distress them.

He explained away the tanking of the rand at the breakfast briefing, saying several factors influenced the exchange rate and that it was important to focus on fixing the economy.

But the government’s 10-year bond yield (which is a benchmark indicator of how risky a government is viewed as being and what interest rate the market would demand when lending to it) shot up too, from 8.88% before Gigaba took to the floor to past 9% during his speech. It went past 9.4% within an hour of the market opening on Thursday morning, nearing the levels of 9.7% when former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene was controversially axed.

Speaking on Thursday, Gigaba said although he would have liked to have been the bearer of good news, “the books are as they are”.

Certainly, the numbers are bad. The revenue shortfall is enormous — R50.8‑billion less than estimates presented in February’s budget. The consolidated budget deficit will now grow to 4.3% of gross domestic product rather than 3.1%. Growth for the year is likely to come in at 0.7% instead of the 1.3% projected. It’s now only expected to reach 1.9% in 2020.

“The news is shocking; the markets are shocked,” Gigaba said.

Bad as they are, the numbers were not unexpected. The poor growth, revenue shortfall and larger deficit were all anticipated by market watchers, although they did come in at the upper end of many estimates.

But, analysts noted, it was the treasury’s lack of commitment to fiscal consolidation that alarmed investors.

“The treasury has seemingly given up fiscal consolidation in the absence of improved policies and politics,” Nedbank’s group economic unit said.

Thanks to a R10‑billion cash injection for poorly managed SAA and R3.7‑billion for the South African Post Office, the expenditure ceiling has been breached and now the state will have to sell its Telkom shares to try and plug the hole.

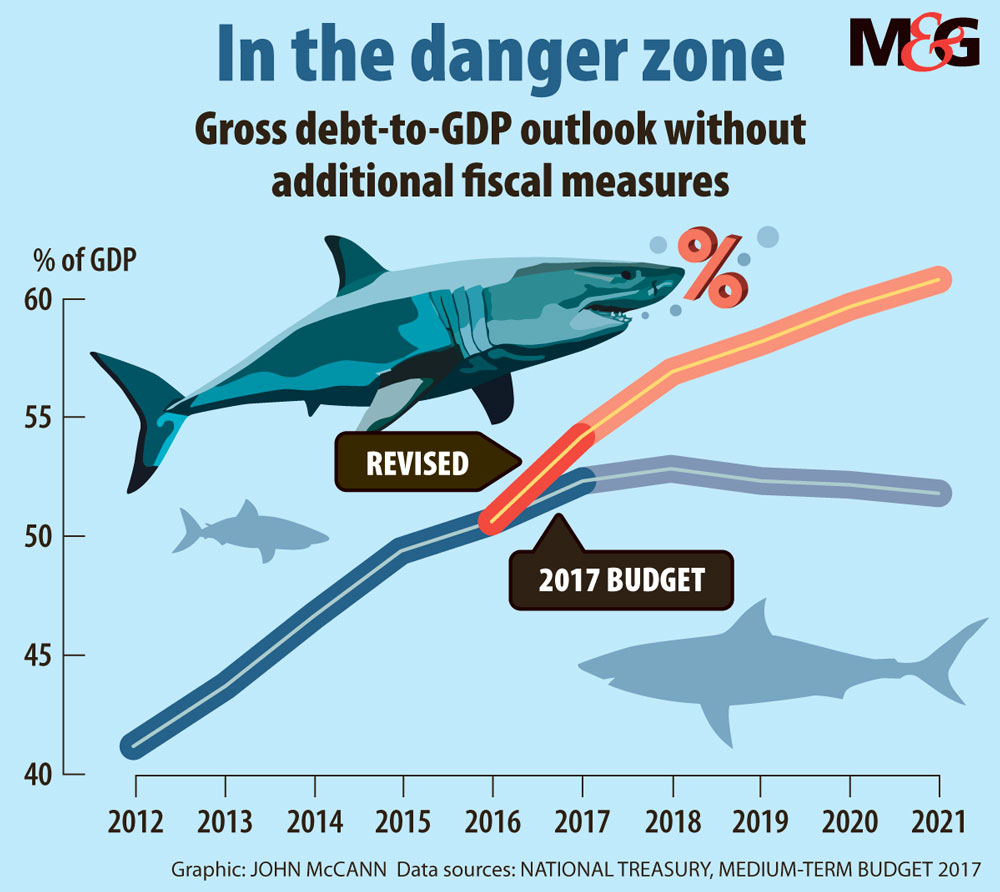

The treasury’s policy statement projects that gross national debt will continue to rise and reach 60% of GDP by 2022 (from 54% previously), and the handling of SAA left investors wondering how robustly Gigaba will tackle poor governance at state-owned entities.

“The market was hoping for bolder moves in this regard,” said Kwaku Koranteng, the acting head of asset consulting at Absa Consultants and Actuaries.

“While he [Gigaba] has highlighted the importance of [parastatals] in the development and transformation of the economic landscape, SAA’s recent and further anticipated bailouts leave question marks around the direction of the entity and what will be done to ensure the sustainability of these institutions and the impact on the fiscus.”

A famine of ideas — or convincing assurances that some were to come — also perturbed investors.

Although Gigaba did say the dismal economic trajectory could be changed with the right interventions, he was scant on the detail.

Asked at a media briefing what tough decisions he would take, he referred to the Cabinet’s 14-point plan. It did little to impress investors when it was announced in July and was criticised as being nothing new or simply inadequate.

Ultimately, Gigaba’s mini-budget offered little vision or hope.

Some observers felt that Gigaba and the medium-term policy statement were perhaps hamstrung in the run-up to the ANC’s elective conference in December, but the minister dismissed this.

“The economy is in crisis now, not on December 22. Right now,” he said, reiterating that action must be taken immediately.

Analysts do not anticipate that the credit ratings agencies (which will be in the country next month) will view the policy statement positively. So the likelihood of further credit rating downgrades remains, which would aggravate the dire situation of the economy.

“Not only is the market likely to hate it but Standard & Poor’s may well downgrade our domestic credit rating in November,” said Nazmeera Moola, co-head of fixed income at Investec Asset Management.

FNB senior economist Mamello Matikinca said her team believed further sovereign downgrades are inevitable and it is increasingly possible that the ratings agencies will act in the next review window (late November and December) rather than in 2018 as they had expected.

This medium-term budget policy statement is a clear acknowledgement of the treasury’s limitations and starkly lays out the likely path if no dramatic action is taken, said Moola.

“You reap what you sow” is no doubt the well-worn adage that inspired Gigaba’s mini-budget speech this week, but it would appear that all that’s on offer is dust.