(Graphic: John McCann)

POLITICS

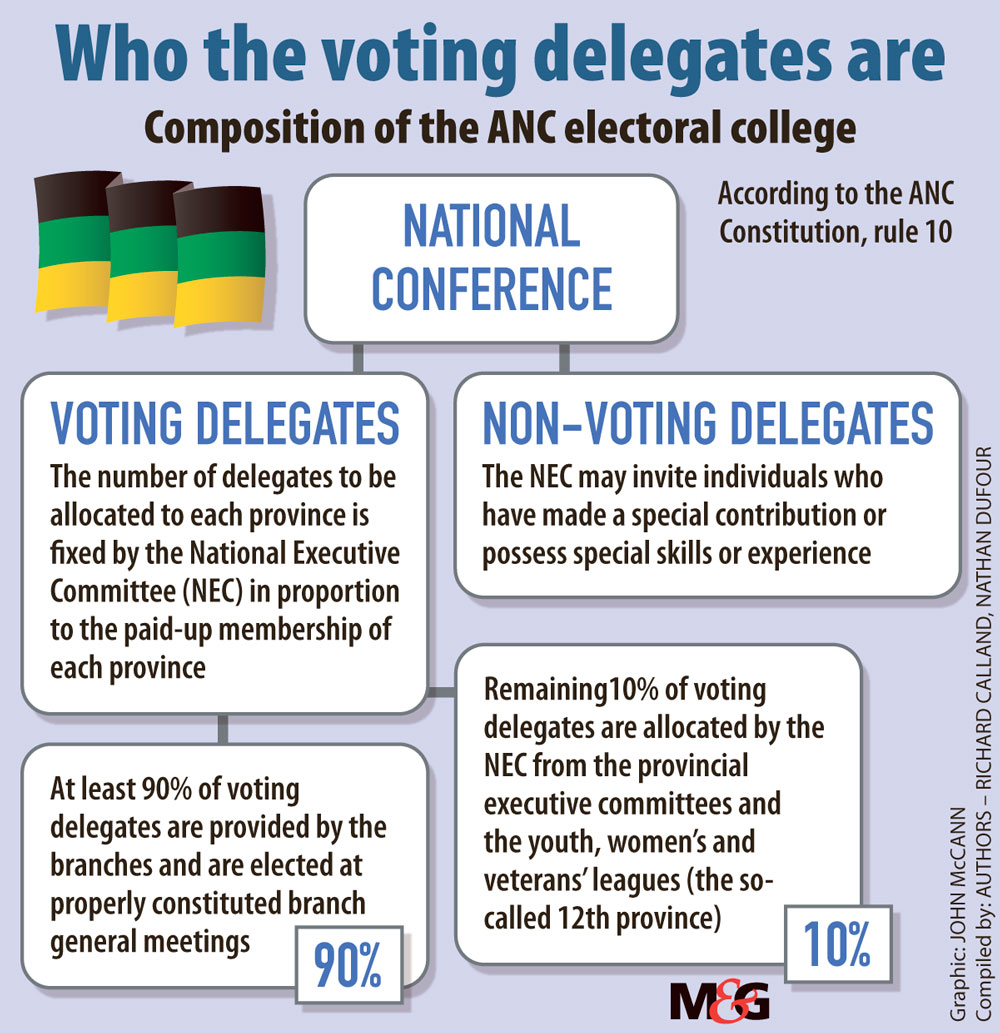

Since 1994, power has shifted dramatically within the ANC. The ruling party’s electoral college (see graphic below), which in December will elect not only Jacob Zuma’s successor as leader of the party but also the all-important 80-member national executive committee (NEC), is notably different from two decades ago.

And, significantly for the ANC’s legitimacy and electoral prospects in 2019 and beyond, its own political balance may have parted company with that of South Africa. Arguably, it no longer represents or reflects the political, economic and demographic landscape of the country.

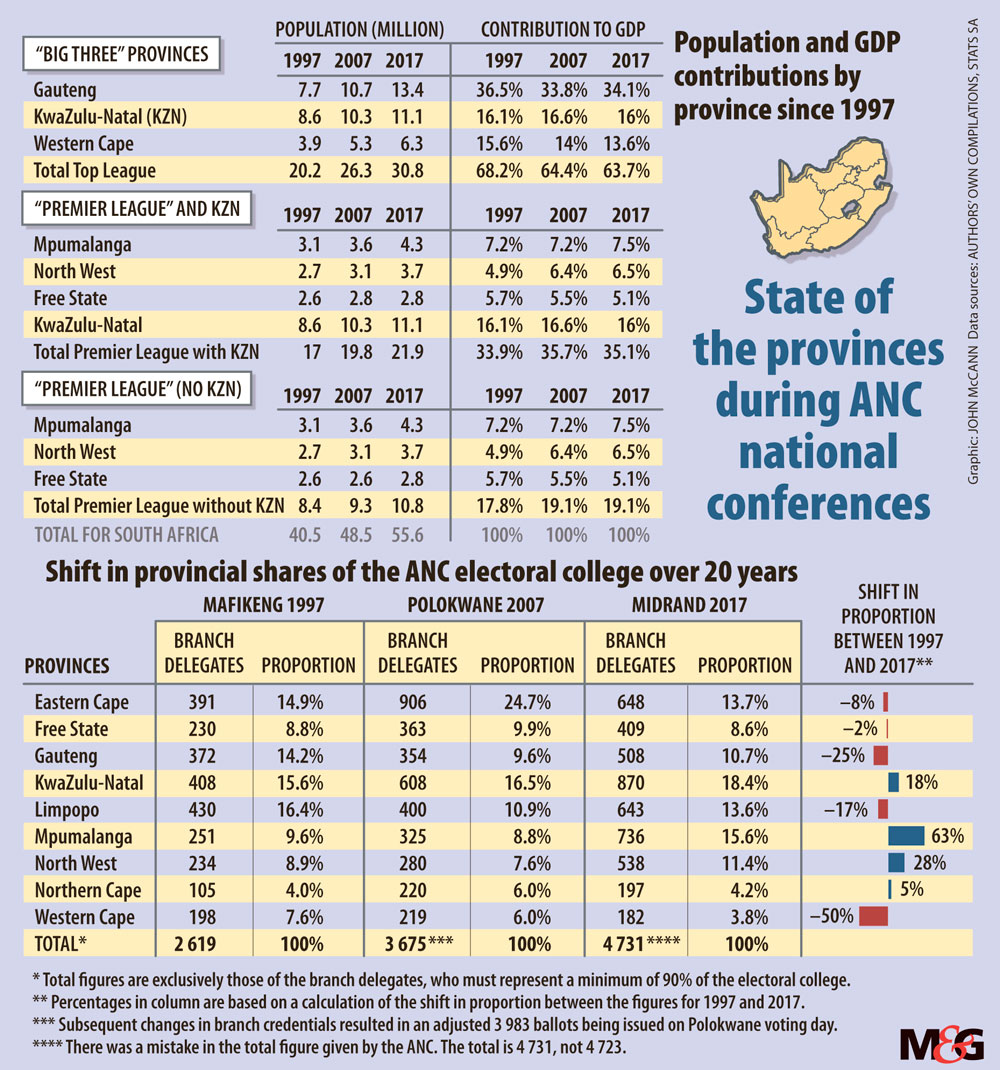

As internal ANC power has moved to provinces such as Mpumalanga and North West, and away from the economic heartbeat of Gauteng and its traditional heartland of the Eastern Cape (see table), interesting questions arise about whether the ANC’s internal democracy is fit for the purpose of leading South Africa.

The political weight of the so-called “premier league” of provinces (Free State, North West and Mpumalanga, plus the additional “founder member”, KwaZulu-Natal) within the ANC family has grown exponentially in the 20 years since Thabo Mbeki triumphed at the 1997 Mafikeng conference. This demands scrutiny as the party heads for what is clearly going to be a watershed five-yearly national elective conference.

So, the two landscapes deserve to be compared: the country’s on the one hand, and the ANC’s on the other.

With more than half the total population of South Africa and nearly 65% of South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP), the provinces of Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape — with their respective metros Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni, Tshwane, Durban and Cape Town in particular — together constitute the economic and demographic epicentre of the country.

Looking at the way the ANC’s NEC attributed the number of branch delegates per province to attend national conferences (electoral colleges) in the past two decades, one could legitimately question whether South Africa’s demographic and economic spread of power is properly converted into a political one in the ANC’s leadership electoral process.

Although the premier league, with or without KwaZulu-Natal, remains a relative outlier from a demographic and economic perspective — accounting for less than half of the big three provinces’ contribution to national GDP and between one-third (without KwaZulu-Natal) and two-thirds (with KwaZulu-Natal) of its demographic weight — it is now punching way above its political weight, representing a massive 35% of all voting branch delegates.

KwaZulu-Natal complicates this analysis. On the one hand, clearly it is a powerful province from an economic and demographic point of view. Thus, the significant power it enjoys within the ANC electoral college (having increased its 15.6% share of the ANC’s electoral college in 1997 to 18.4% now), is in fact a better reflection of the province’s place in the country as a whole. But it is also a founder member of the premier league and a part, therefore, of the project to shift power away from the “cosmopolitan” dominance of the so-called “1996 class project” and the Mbeki years.

In other words, KwaZulu-Natal — especially, of course, during the Zuma era — has claimed greater political power within the ANC for very particular factional and ideological reasons, especially when it is seen as politically joined at the hip with the core premier league faction of the North West, Free State and Mpumalanga.

Since 1994, the big three’s political power within the ANC has seen a sharp overall decrease in voting power within the ANC electoral college, with Gauteng and the Western Cape having lost respectively 25% and 50% of their respective shares of the ANC electoral college since the 1997 Mafikeng national conference.

Meanwhile, the share of the premier league has increased from 27% in 1997 to 35% in 2017 (without KwaZulu-Natal), and from 42.9% in 1997 to a majority share of 54% in 2017 when KwaZulu-Natal is included in the equation.

So, although the big three’s fall in share of the electoral college (from 37.4% to 32.9% over the past 20 years) matches its fall in its collective contribution to GDP (down from around 68% to 63% over the same period), there is now a remarkable disparity between its contribution to GDP and its share of the votes in the ANC’s electoral college.

This dramatic increase in the power of the premier league has never appeared more clearly than during the current ANC electoral process. Although the premier league’s contribution to GDP is still under 20%, even including KwaZulu-Natal, and has only increased by about 2% in the past 20 years, its share of the electoral college is now over 50%.

But if data collection allows one to clearly identify and quantify these trends, what are the implications for South Africa’s democracy and its political direction?

In spite of the ANC’s record decline in support at the 2016 local government elections (see our analysis at The Paternoster Group), it has been in the driving seat of the country for more than two decades. Questions about the democratic legitimacy of its leadership deserve careful scrutiny, not least because of this leadership’s control of the selection process of those who sit in Luthuli House or occupy key functions in the public administration and, to a lesser extent, in the judiciary.

In other words, the ruling party’s dominance of electoral politics and therefore government means that the process by which it elects its leaders deserves to be in the spotlight — not least because, as we have seen during the Zuma years, the political character and composition of the NEC has a huge impact on the power of the president of the ANC and, thereby, the president of the country. Zuma has survived several attempts to recall him as president of South Africa because he retains the support of a majority in the NEC, who owe their power to Zuma’s patronage.

Put even more clearly: whoever controls the ANC’s electoral college controls South Africa, especially without a viable electoral alternative in national elections, or at least in the five national elections held since 1994.

At least those who run Luthuli House seem to have recognised the significance of this internal trend and the effect of the growing influence of some provinces within the ANC’s electoral college.

And, indeed, the ANC has been moving quickly in recent weeks to empower its branches to withstand interference from the provincial and, to a lesser extent, regional leaderships. In previous ANC elections, it was clear that the provincial structures remained powerful gatekeepers and intermediaries between the branch general meetings and the actual national conference. That is why there has been such a fierce — and at times, deadly — contest for provincial power in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga, in particular.

Based on the current trends at the branch, subregional and regional levels, it seems that the branches are trying to make the best use of this new window of opportunity to play their role as the basic unit of the ANC’s huge machinery, with some openly disobeying the choices expressed by the provincial leadership. But the potential backlash from this could well be a dangerous rise in political instability at this late stage of the nomination process.

On the other hand, provincial and regional leaderships have retaliated by expressing their intent to proceed with their provincial executive council, regional executive council and other provincial general council meetings despite the NEC order not to hold such meetings less than two months before the national conference.

This trend of ever-growing political control at the periphery over the economic and demographic core of the country seems to be counterintuitive, particularly when one looks at countries such as France, where poorer regions struggle for attention against affluent urban centres, with huge political consequences, such as the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the victory of Donald Trump in the United States.

Indeed, the success of Trump’s presidential campaign in convincing those at the periphery that Washington had overlooked them for too long bears a certain resemblance to what is happening in South Africa: a parasitic, populist faction appears to have eaten its way into the very core of the ANC, with profound consequences for South Africa and the ruling party.

Nathan Dufour is a senior research associate with the Paternoster Group: African Political Insight. Richard Calland is a founding partner of the Paternoster Group and author of Make or Break: How the Next Three Years Will Shape South Africa’s Next Three Decades (2016) and The Zuma Years (2013)