(John McCann/M&G)

A state job may be cushy, but paying civil servants is becoming a major problem for the fiscus.

The public service’s soaring wage bill is one of the key risks to the state’s ability to keep the country’s finances on a sustainable path, according to a bleak medium-term budget policy statement delivered on Wednesday.

Spending on state remuneration has grown more quickly than the overall budget over the past eight years, and now accounts for 35.3% of consolidated expenditure, up from 32.9% in the 2008-2009 financial year, according to an analysis of compensation trends that accompanied the budget update.

The average public servant’s salary is almost R338 000 a year, or just over R28 000 a month. This is about 47% more than the average monthly earnings of a worker in formal, non-agricultural employment, which was just over R19 000, according to Statistics South Africa’s latest quarterly employment survey.

According to the treasury’s examination of tax data, public servants in general also received better remuneration than taxpayers at every income level, except at the very top.

The income of the median taxpayer in 2014 was just under R100 000, but that of the median public servant was more than R260 000, according to its analysis.

Only taxpayers in the 95th percentile, who earned about R682 000 a year, did better than public servants who earned about R563 000.

Only interest payments have grown faster than the wage bill, according to the treasury, and the combination of these two factors has resulted in much slower growth in spending on other things such as capital investment and goods and services.

Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba was reluctant to put a figure on how much the state could stomach in the upcoming wage negotiations with public servants.

“We will not go to unions to say: ‘Accept a wage cap at this level,’” Gigaba said, adding that the government would outline what sacrifices and pains it would make to meet unions halfway without spelling out what these would be. He said the government was still formulating its position on negotiations and did not wish to make any pronouncements before the talks.

However, the medium-term budget policy statement did allow for an increase of 7.3% over the coming three years to accommodate improvements in conditions of service. This is far below the 10% to 12% wage increases that public-sector unions are seeking.

The treasury warned that many departments “are already at risk of exceeding this limit, even assuming that personnel numbers do not increase”.

Despite the souring of political relations with the unions because of the deterioration of relations within the tripartite alliance, Gigaba said the unions were “quite alive to the challenges we are facing”.

Although labour is aware of the financial challenges faced by the state, trade union federation Cosatu differs from the state about how to address them.

“Unions are not blind to the fact that you can’t have the whole budget going to wages,” said Matthew Parks, Cosatu’s parliamentary co-ordinator.

But he said the state could not negotiate smaller increases for workers without, among other things, addressing a bloated Cabinet of 78 ministers and deputies, or dealing with the billions of rands in irregular or fruitless and wasteful spending flagged by the auditor general.

The state also needed to consult workers to determine which posts were critical for service delivery and which were not, Parks said.

“It is difficult to have faith in government when it freezes critical health and education [posts] and wants to reduce police posts, yet we see a massive rise in the size and budget of the presidency and other policy departments,” he said.

The analysis of remuneration trends revealed that increases in spending have been driven mainly by salary increases and not by an increased headcount.

Between 2008-2009 and 2016-2017, compensation spending increased by about 37% in real terms, the treasury said, but about a quarter of the increase resulted from expanded employment, with the remaining three-quarters due to higher remuneration.

State employment peaked at about 1.3‑million in 2012-2013 and has since fallen by about 22 000. Despite the number of employees stagnating, real remuneration for each employee has continued to rise, reflecting an implicit trade-off between headcount and salaries, it said.

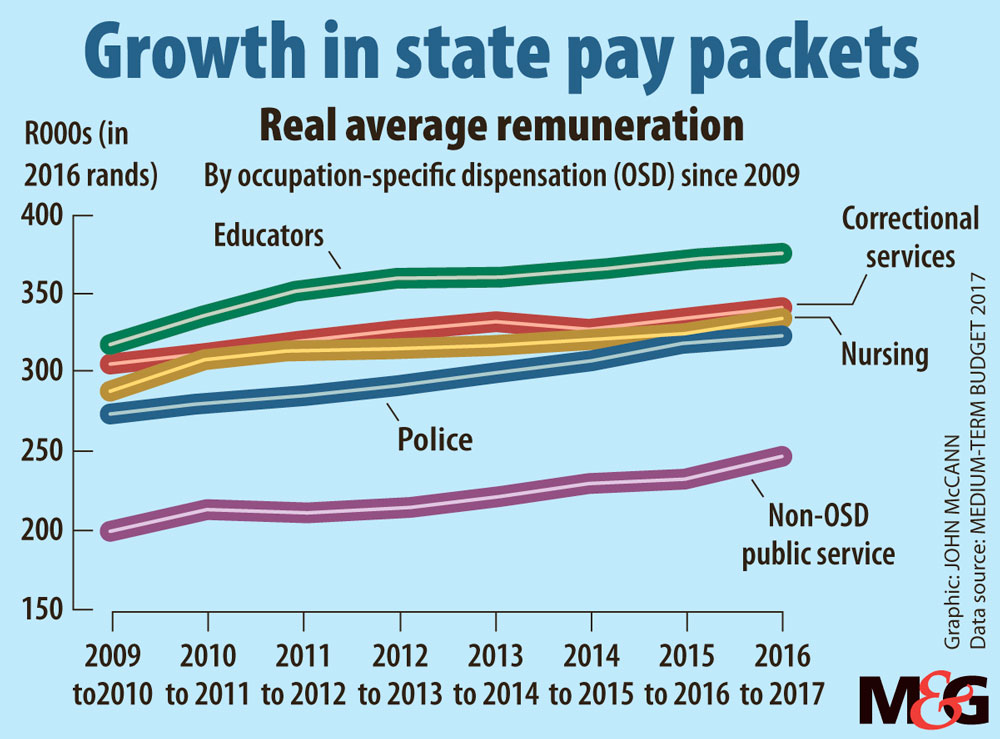

According to the treasury, the rise in remuneration was driven by several factors, including above-inflation increases to basic salaries because of annual cost-of-living adjustments; the introduction of occupational specific dispensations (OSDs), which led to a “level shift” in the pay and conditions of service of teachers, nurses, police officers and others; and human resources policies, such as promotions and salary progressions, which have led to an upward drift in the distribution of personnel across pay scales.

Progression and promotions are intended to be incentives linked to performance but in many sectors they have become automatic, and on average increase the government’s wage bill by 1.5% each year, according to the treasury.

These human resources practices include notch progression (when employees move up the scale within their salary level); promotions as vacancies arise and the upgrading of personnel in line with revised job descriptions; and the wholesale promotion of personnel from one salary level to another.

The treasury cited the example of 2013-2014, when all clerks were upgraded from salary levels one to four to level five, and those on level five were upgraded to level seven.

As a result of these policies, in the past eight years the proportion of public servants in the lowest four salary levels fell from 26.8% to 20%, and the proportion of staff in the middle to higher salary level rose from 43.8% to almost 51%.

The introduction of OSDs in 2008, which was designed to attract skilled employees to the public sector and retain them, has also been an important factor. Non-OSD public servants earn significantly less than designated occupations, with teachers earning more than any other large OSD group, the treasury said.