John McCann/M&G

One of the worst elements of the unflinchingly harsh medium-term budget on Wednesday was just how badly the government is doing at raising the taxes it needs.

It has blamed the gaping tax shortfall on poor economic growth but analysts argue it is also because the public are fed up with corruption and wastage.

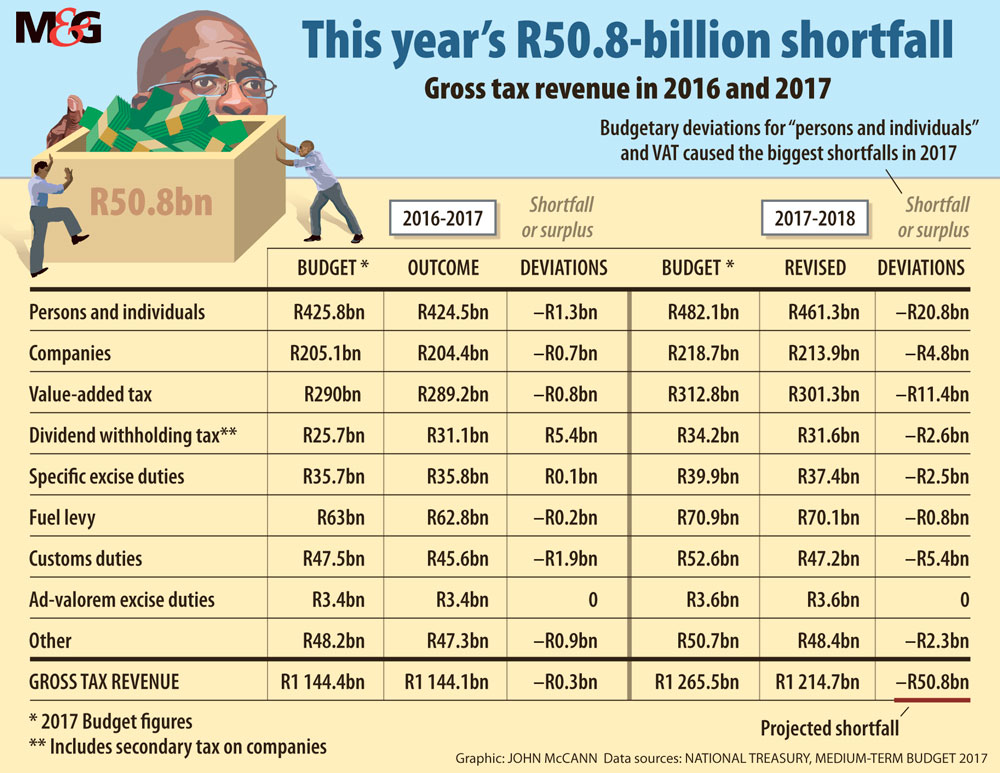

Cumulatively, the revenue shortfalls in the coming three years are expected to reach almost R210‑billion, starting with a R50.8‑billion gap for the 2017-2018 year.

This hole has forced the government to jettison promises of fiscal consolidation — or commitments to reduce the budget deficit and its reliance on debt.

The state’s borrowing as a percentage of gross domestic product is now expected to soar to almost 60% and the deficit, instead of shrinking, will hover at 4% for the next three years.

Expectations are that this will hasten a credit ratings downgrade and possibly an International Monetary Fund bailout.

Tom Moyane, the commissioner of the South African Revenue Service (Sars), said poor economic performance is responsible for the scale of the shortfall. Revenue growth rose by 5% for the first six months of the year, well below the target of 10.7%, with economic growth forecasts being slashed from 1.3% to the current 0.7%.

The real hit to revenues came from personal income taxpayers — collections undershot expectations announced in the February budget by R20.8‑billion, which is by far the largest contributor to the shortfall.

This tax category has been affected by low bonus payments, moderate wage settlements, job losses and a slower expansion of public-sector employment, according to the medium-term budget policy statement.

The link between tax collection and economic growth cannot be ignored. Tax buoyancy — the expansion of revenue associated with economic growth — has fallen sharply in the past two years, according to the statement.

Between the 2010-2011 and 2015-2016 financial years, each percentage point of GDP growth led to a 1.23% growth in gross tax revenue. But last year, tax buoyancy fell to 1.01%, despite tax policy changes intended to raise an additional R18‑billion. This year’s outlook is hardly better, with a buoyancy of only 1.02% estimated.

Nevertheless, the treasury appears to be keenly aware of the looming problem of tax morality, which has to be seen against a backdrop of scandal after scandal at state-owned enterprises and members of President Jacob Zuma’s administration being implicated in widespread allegations of state capture.

“Policy and administrative factors may also be contributing to the shortfall. Behavioural responses to tax increases may be larger than anticipated and revenue could perform below expectations even if taxes are hiked,” according to the medium-term budget policy statement.

“Compliance concerns are mounting in the context of tax administration challenges and weakening tax morality.”

Professor Jannie Rossouw, the head of economic and business sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, said: “It’s a growing concern because we see the misappropriation of our tax money and the more misappropriation that we see, the bigger this problem of tax morality, tax avoidance and tax evasion will become.”

The only way the government can address this is to instil the confidence that the government is spending taxpayers’ hard-earned money responsibly, he said.

“Press charges against the Guptas tomorrow and tax morality will improve,” Rossouw said.

This was echoed by Ian Matthews, the head of business development at Bravura, an independent investment banking and advisory firm. He said rising public concerns about corruption, wastage of public funds and inefficiencies in service delivery are clearly affecting the willingness of South Africans to comply and pay their taxes.

“Taxpayer trust and confidence levels have plummeted dramatically in recent times,” he said, citing the fruitless and wasteful expenditure on Zuma’s Nkandla homestead, the still unresolved sale of South Africa’s strategic fuel stocks, the billions of rands lost because of corruption and the inept management of state-owned entities such as SAA and Eskom.

“South Africans need assurance that government will keep expenditure in check, and even cut costs at nonperforming entities,” he said.

But the impact of tax morality on revenue is very difficult to measure or to quantify, said Nazmeera Moola, co-head of fixed income at Investec Asset Management.

“You are seeing personal income taxes surprise significantly on the downside,” she said, adding that some of this is probably the result of jobs being shed, bonuses not being paid and lower wage increases. But there might also be an element of tax morality, she said.

Rossouw said the only way to deal with these dramatic shortfalls is to cut spending.

“As with an ordinary household, if your income falls away, you have to reduce your expenditure,” he said, adding: “But this is not an [medium-term budget policy statement]; this is a wish list.”

Apart from a few measures to deal with the bad news, such as efforts to sell part of the state’s holdings in Telkom to bail out SAA and the South African Post Office, the really difficult decisions have been deferred until the 2018 February budget. Conveniently, this will also be after the ANC’s December elective conference.

The state is counting on R15‑billion more tax revenue in the 2018-2019 year, although this was pencilled in in last year’s February budget and the government has yet to say how it will achieve it. Gigaba didn’t announce any new tax measures and gave no hint of what appears to be the most likely tool — an increase in the value added tax rate.

Regarding spending cuts, any major decisions are now in the

hands of a presidential committee, which will “consider options” and make an announcement in the 2018 budget.

“This has really raised the bar for the February budget to a level that I do not think anyone can deliver on,” Rossouw said.