Ultimately

The R321 cuts straight through the centre of the Theewaterskloof Dam in Caledon. Before you approach the bridge that traverses the water, the scene looks more like the Namib Desert than it does a dam. Dry white sand, kicked up by the Cape winds, fills the air. Below, dunes embrace ashen and dead tree trunks.

A short drive on is the Theewaterskloof Sports Club, which is eerily quiet. Picnicking and swimming are permitted, but boats may no longer be launched into the water — understandably so: it is bone dry at the jetty and the russet water is now some distance away.

This dam is at the centre of the Cape water crisis. It is the largest feeder of drinkable water to the residents of Cape Town.

It is also the emptiest. With a 480‑billion-litre (or 480 000-megalitre) capacity, Theewaterskloof amounts to 53% of all dam-water storage for the city. But at 27% full, it is at the lowest level of all the dams. This time last year, it was at 51% of its capacity. The year before that, it was at 74%.

Overall, the City of Cape Town’s dam levels this week totalled 38.2% — keeping in mind that the last 10% of water contains sludge and organic matter and is not usable.

Cape Town is experiencing its worst drought since 1904, and the next rainy season for the region is several months away.

The day the dams run dry, dubbed Day Zero, is expected to arrive in March next year. In the run-up to that moment, consumption is likely to be as low as it will go — 680-million litres a day, against a target of 500-million litres. It’s also improbable that leaks in the water infrastructure will be improved much further. (See “Waging war on leaks won’t win Mother City’s water battle”.)

The task now is to find other water sources before the taps run dry.

The city is pursuing several options but, because of its proximity to the sea, desalination is key to mitigating the crisis. But the process is already incurring delays at a time when they can be ill afforded.

Tenders put out for small-scale temporary desalination plants received nonresponsive bids and have had to be readvertised.

Desalination experts say plants that will fulfil the city’s needs take at least six months to get going. In August, Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille said 500‑million litres a day — the targeted water consumption level for the city — would be produced with new technology, including desalination, water reuse and extracting groundwater from aquifers.

“Unfortunately, there are no quick solutions. There are no plants waiting around to be deployed,” said Chris Braybrooke, the general manager of Veolia Water Solutions and Technologies.

Veolia has built several desalination plants in South Africa, including the country’s largest in Mossel Bay. “Something like what we built in Mossel Bay would take two years to be deployed,” he said.

Cape Town had been exemplary in its day-to-day management of the water system, he said, but desalination projects take time and “ideally” the tender should have gone out six or nine months ago.

The Mossel Bay plant was built in response to a 2010 drought and was up and running in 2011. It can produce 10-million litres of drinkable water a day. But, like many desalination plants that are built in response to a crisis, it is now idle. “Many of the dry regions of the world are in the process of building or have desalination plants,” said Claire Pengelly, water programme manager at Green Cape. “But the big fear is – what happened in Australia – there is a massive drought, everyone starts panicking, desalination is built and then the rains come.”

In an emergency, things can move a little faster, Braybrooke said — although, with desalination plants, environmental impact assessments still need to be done and marine consultants must be brought in.

Sea water differs in composition, so each desalination plant must be adapted to ensure the pretreatment is correct, Braybrooke said. The West Coast, in particular, is high in organic content and includes phenomena such as red tides, and a desalination plant must be able to deal with that. To put a standardised plant up and expect it to work could be a total disaster, he said.

He added that Cape Town is well aware of the complexity of establishing a desalination plant. Still, Cape Town is confident it can pull off the water augmentation programme, which it describes as being “unpre-cedented in scale”.

“We are doing in months what it would usually take years to do,” the city said in a statement. “We are able to progress because of our proactive long-term planning and good governance mechanisms.”

If the city taps did run dry, industry will have to shut down and poor sanitation could see the rapid spread of infectious diseases.

“I think desalination is an absolutely valid approach to follow now, given the crisis. In Cape Town, there are no more sites to dam. Berg River Dam was touted to be the last dam — from there on, Cape Town should save water,” said Kobus van Zyl, a University of Cape Town professor and hydraulic engineer.

“The problem with desalination is just the cost,” he said.

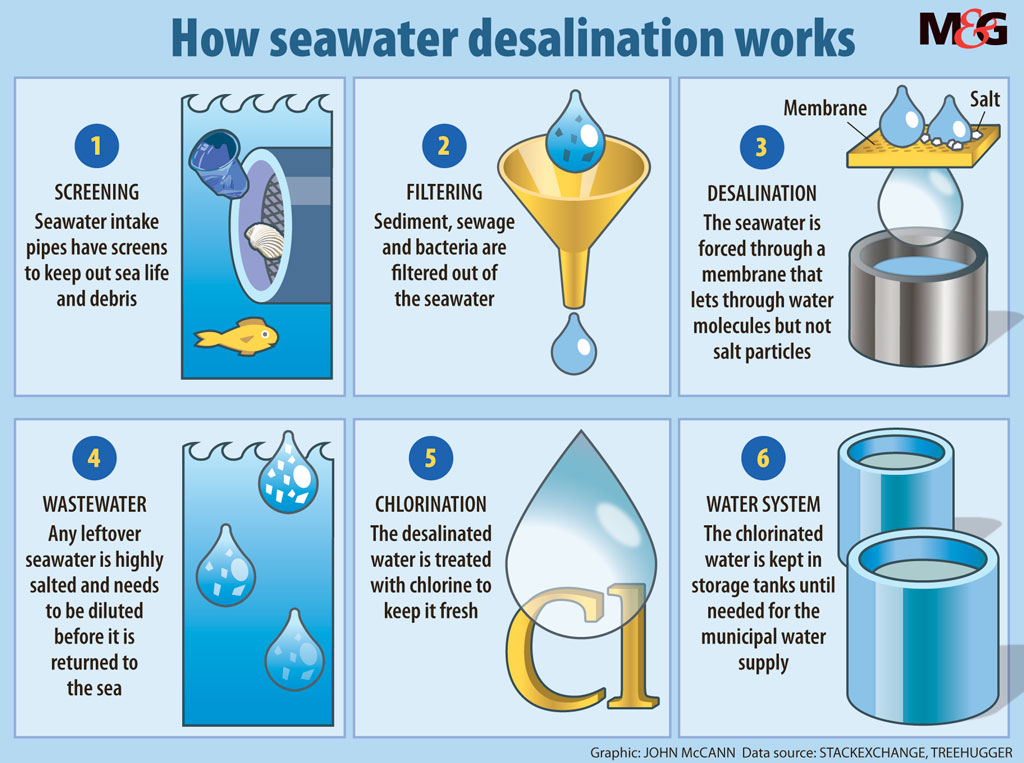

Apart from the cost of building a desalination plant, the cost to produce potable water can be six times higher because forcing seawater through a membrane is an energy-intensive process.

According to the Water Research Commission, under normal circumstances Cape Town can produce water for R1.25 per 1 000 litres using a mix of water sources. But the cost of producing water from a large desalination plant at the coast is between R5.80 and R8.30 per 1 000 litres.

“What people forget is that, in a drought, the cost of treatment will go up regardless,” said Braybrooke, adding that when there is a shortage you can’t be choosy about the quality of water.

There are also costs related to shutting off a desalination plant, he said. “This technology does not like to be turned on and off.”

For one, he explained, you are working with membranes, each of which is expensive. When mothballed, they need to be preserved with special chemicals to ensure they don’t lose their functionality.

Whatever the measures, fulfilling the city’s water needs is not going to be cheap. It was originally estimated that Cape Town would have to divert R3.3-billion from its budget to institute the first phase of emergency measures. Approval for a diversion of funds was granted by the national treasury this week. However, the city cannot yet say how much the emergency programme could cost, other than to say it is a “multibillion-rand” initiative.

“The total cost of the programme will be available when the various procurement processes have been completed. It is currently a fluid process based on tender inputs,” said Johan van der Merwe, the city’s mayoral committee member for finance. He said the city is confident it can finance the emergency programme by reprioritising funds and using savings and cash reserves.

“Bringing so many new technologies online simultaneously at multiple sites around the city is expensive and, as such, under the Municipal Finance Management Act, our finance team is working on making funding sources available, including cash, reprioritisation of existing water projects, a concessionary loan from an external funder, and curtailing expenditure elsewhere in the administration,” he said.

Tariffs, including water and rates, have been established for 2017-2018 and cannot be adjusted, which means consumers will not face higher costs for the remainder of this financial year.

“While the city will do everything in its power to curb expenditure across the administration to reduce the impact on future tariffs, we can expect tariff increases significantly above inflation in the 2018-2019 financial year,” Van der Merwe said.

But the city is concerned that a user-funded approach will not be sustainable without large population growth, which would produce more favourable economies of scale, so it is exploring other funding models that won’t overburden residents financially, Van der Merwe said.

The treasury’s green light will also allow the city to bypass some red tape and speed up procurement processes.

Waging war on leaks won’t win Mother City’s water battle

Minister of Water Affairs and Sanitation Nomvula Mokonyane met Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille and other officials early last month and urged the city to fix leaks as a way to further prevent unnecessary losses.

But experts say, at this stage, it’s no silver bullet to solve the city’s problems.

Kobus van Zyl, a hydraulic engineer in the University of Cape Town’s department of civil engineering, said, in fact, the city has the best water infrastructure in the country when it comes to leaks.

“You can’t get leakage to be zero in any system. There will always be some and you won’t find them all, because some will be hidden from view underground.”

The infrastructure leakage index rates how leaky a system is. Cape Town, at 2.2, is the best in the country, said Van Zyl. Johannesburg is at about eight.

“If the city spent all the money in the world on leakage reduction, they could get it down to maybe 8% instead of 16%. That is part of the solution, to continue to reduce leakage. But if you can spend the same money and get people to use water more efficiently, that is a better solution,” he said.

“For the same money, you could replace all shower heads with water-efficient shower heads. As a water manager, there are various things you can do. It is about how to spend the available money in the best way to get where you want to be.”

In a water crisis, you reduce consumption and look for short-term gains in supply, which is what the city is trying to do, he said.

Reducing pressure in the pipes reduces stress and helps to contain leakage. But intermittent supply, dubbed water shedding, as a general rule is very bad for the water system. When water is shut off, pollutants can enter externally into cracked pipes. The air in the system also increases the incidence of burst pipes by 300%, Van Zyl said.

“Cape Town has been pretty good in resisting instituting intermittent supply. What they are doing now is probably the right thing to do. This is really an emergency short-term measure … It’s not a good thing, but not as bad as the alternative.”

Ultimately, Cape Town faces a large technical failure brought on by a failure to plan for the worst, he said.

Van Zyl said planning water infrastructure to meet projected water demand is critical and the custodian of that, the department of water affairs and sanitation, should be the driver of long-term planning and thinking about water resources.

The department has said it will fast-track the implementation of the Berg River-Voëlvlei augmentation scheme, which it hopes to complete by the winter of 2019. There are also plans to start work on the raising of the Clanwilliam Dam wall.

The minister has described the water shortage as “the new normal”. — Lisa Steyn