Is Eskom, and by extension the country, facing a financial reckoning? The beleaguered utility is deemed to be too big to fail, given the government’s exposure to its debt and the fact that it is the economy’s major supplier of power.

But in light of the state’s poor financial position, outlined in the recent medium-term budget policy statement, it may be too big to bail out.

Eskom gave assurances this week that it is not running out of cash and that its “projected liquidity is at manageable levels”. This followed a report by Moneyweb that the company wants to sell part of its loan book to the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), querying whether Eskom is in trouble.

But the treasury said in reply to questions that it “is very concerned with the liquidity position of Eskom and has been working closely with [the department of public enterprises] and Eskom’s treasury … to ensure that the entity remains financially sustainable”.

The National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) is currently considering an application by Eskom to increase tariffs by 20% for the coming year and a decision should “greatly improve Eskom’s financial position”, the treasury said.

Since the utility announced its financial results in July, the question whether its financial state may be worse than expected and may require a government bailout refuses to go away. Concerns have been compounded by governance failures, a qualified audit opinion and allegations of corruption at Eskom.

These have alarmed the PIC, which sees Eskom as a material risk to its clients, it has said.

The PIC holds more than R84‑billion in Eskom bonds on behalf of its largest client, the Government Employees Pension Fund.

“Repeated governance failures by the board and Eskom’s executive management, as well as the institution’s long-term debt accumulation, do present material risks to the PIC’s clients who are exposed to Eskom bonds,” said head of corporate affairs Deon Botha.

The state-owned asset manager is developing a framework to better manage how it invests in Eskom and other state-owned enterprises.

In an analysis of Eskom’s latest financial results, consultancy firm Eton Group found that the utility is having to service debt without the financial means to do so. “Eskom is not generating enough cash through operation and electricity sales revenue to cover the interest on its borrowing,” the report said. “This equates to using one credit card to pay off another.”

Eskom’s reliance on borrowing was flagged at its annual results presentation by its now suspended chief financial officer, Anoj Singh.

“It’s common cause that we are in a net borrowing position and our ability to continue as a going concern is premised on the basis that we have continuing access to debt capital markets,” he said.

“If something catastrophic had to happen tomorrow that limits our access to debt capital markets, which we are not aware of currently, then we would have to approach treasury.”

But Eskom’s ability to raise funds on capital markets since Singh delivered these words is not clear.

For the 2017-2018 financial year, Eskom planned to raise R71.7‑billion. At the start of the year, it said it had secured just over R32‑billion, the bulk of which — R27.4‑billion — came from deals with development finance institutions (DFIs). Eskom said it had secured about 53% of its funding requirements for the year, which included about R6.3‑billion in available bank facilities.

It was seeking further funds from other sources, including R15‑billion from domestic and international bond issuances.

But the company has not issued bonds on public auction since August 2014, thanks to private investors’ reluctance to take them up, even with government guarantees.

There is some speculation that there may be a discrepancy between the funds Eskom said were available at the beginning of its financial year and what has actually been committed, said Nazmeera Moola, the co-head of fixed income at Investec Asset Management.

There is also concern that some of the committed funds announced at the beginning of the year may now be on hold because of lenders’ concerns about the utility’s governance, notably because of the qualified audit report and the poor performance of its board.

In response to questions, Eskom said that, to date, it has secured 57% of the funding required for this financial year, although it would not disclose where the relatively small amount of additional money has come from.

But reports suggest lenders, including banks, do appear to be flexing their muscles and are threatening to freeze the company’s credit lines unless its governance crisis is resolved. Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba, in his medium-term budget, promised that Eskom would have a new board in place by the end of November.

Given the qualified audit opinion and other governance concerns, Eskom did not answer the question whether any of the committed funding for the year — notably the R27.4‑billion from DFIs and the R6.3‑billion in available bank facilities — is now in doubt.

But it said its liquidity is not dependent on the banks’ facilities or its debt being rolled over.

The treasury said it is working with Eskom and the department of public enterprises to help the utility to secure the funding identified in its funding plan.

The government has issued R355‑billion in guarantees to Eskom, about R210‑billion of which has been used. Should the utility be unable to pay its bills, this could trigger a call on the guarantees, which would be too large for the fiscus to handle.

“As government is guarantor of a significant portion of Eskom’s debt, it has become a significant risk to the entire economy,” Gigaba said in his speech last week.

Moola cautioned that it is very difficult to ascertain Eskom’s true funding position because of the lack of visibility surrounding its arrangements.

If Eskom is able to draw down on all the funds announced as committed, then the company should get through this year without a liquidity issue, she said. But if some of the facilities have been withdrawn because of lenders’ concerns and particularly if Eskom does not have a new board by November, then the utility could be facing a liquidity issue, she said.

However, if there were liquidity concerns, they would probably have been tabled in the mid-term budget statement, she added.

Given the constraints on the budget, there are few ways for the government to support Eskom in the short term. It could borrow more — and widen the deficit. Assets could be sold, but this would involve a process and it is unlikely that it would be completed by the end of the financial year, she said.

In public hearings on the tariff applications, civil society, industry and economists have focused on Eskom’s financial state.

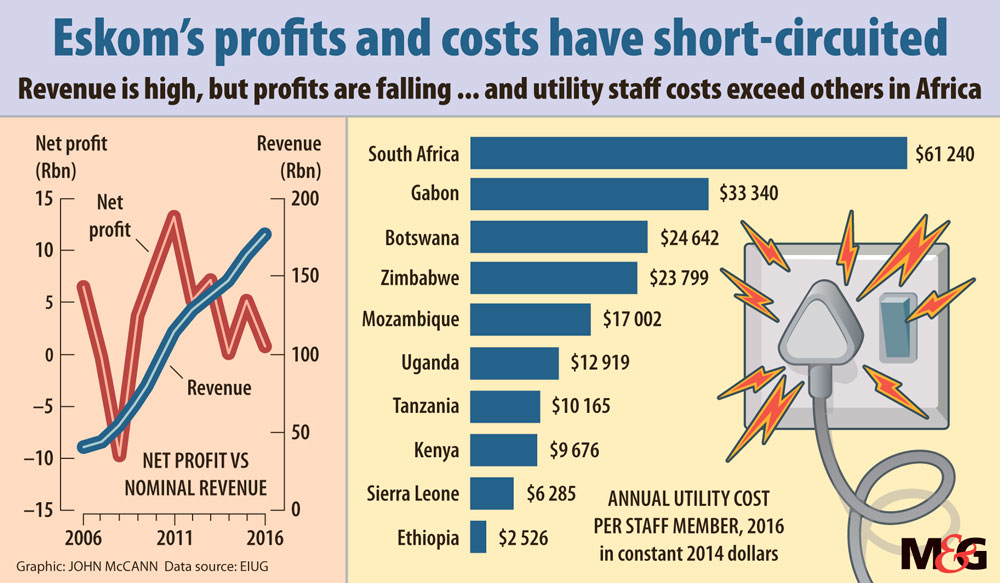

The government and Eskom appear to be counting on a favourable tariff decision to stabilise Eskom but stakeholders have warned that the economy cannot sustain further steep increases. They are particularly critical of Eskom’s poor cost controls and its crippling capital expenditure programme, which is increasingly being seen as unnecessary given the decline in demand for Eskom-generated electricity.

Experts warn that dramatic and difficult decisions about Eskom’s future have to be taken. In a presentation to the Nersa hearing, Grové Steyn, of Meridian Economics, said one way for Eskom to stabilise its financial position would be to decommission some of its older power stations and halt its completion of the Kusile power station’s units five and six. This could free up about R17‑billion, in spite of possible claims by contractors, according to his preliminary research.

“My impression [of Eskom’s financial position] is that it is dire,” Steyn said.

Eskom poses a systemic risk to the country because of the government’s guarantees and the exposure of government pensions, he said, also pointing to the utility’s importance to the economy as its major electricity supplier.

It is not clear whether Eskom is, in fact, facing an imminent funding crisis, he said, but it is clear that, in the long term, the company has to stop the haemorrhaging — and cutting back on its costly capital expenditure programme is a way to do this.

PIC frets about its parastatal exposure

The Public Investment Corporation (PIC) this week said it is extremely concerned about Eskom’s continued corporate governance failures, given the risks that the utility poses to its investors.

The corporation is developing a framework to direct how it should invest in state-owned entities in future. Preliminary research and legal analysis on this has been concluded and presented to the PIC board. This will be discussed with its clients, after which it will be referred to the finance minister for consideration on how best it could become a policy directive for future PIC investments.

The public asset manager invests on behalf of a number of clients, including the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF). The fund, which has about 1.27‑million active civil service members and 437 000 pensioners and beneficiaries, holds almost R86‑billion in Eskom bonds and bills.

Eskom is heavily reliant on raising funds but it and other parastatals have been struggling to sell their bonds in the open market. This has led to concerns that the PIC has become the buyer of last resort, although both it and the GEPF strongly deny this.

The repeated governance failures by Eskom’s board and its executive management, and the utility’s long-term debt accumulation, present material risks to the PIC’s clients, head of corporate affairs Deon Botha said in reply to questions.

“At the same time, it must be understood that Eskom, to date, has not defaulted on any of the PIC’s bond investments,” he said, adding that the majority of Eskom’s bonds are government guaranteed.

In response to reports that the PIC and other lenders have instructed Eskom to appoint a new board by November, he said that, legally, it cannot prescribe when and how the current Eskom board should be reconstituted. Nevertheless, he highlighted the minister of finance’s recent comments in the medium-term budget policy statement that, in its current operational state, Eskom presents a significant risk to the fiscus.

“Given its exposure to Eskom debt, the PIC trusts the institutional, governance and financial management problems at Eskom will be dealt with urgently by government as the shareholder,” he said. — Lynley Donnelly