'More radical critics have described tax havens as a scourge that should be eradicated

Ho hum. Another day, another leak showing how big companies, the rich and the famous make use of tax havens. These leaks have become commonplace in recent years. The latest, and largest yet, are the Paradise Papers, the 13.4-million documents released this week exposing clients of the Bermuda-based law firm, Appelby which has offices in other tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands, the Isle of Man and Guernsey.

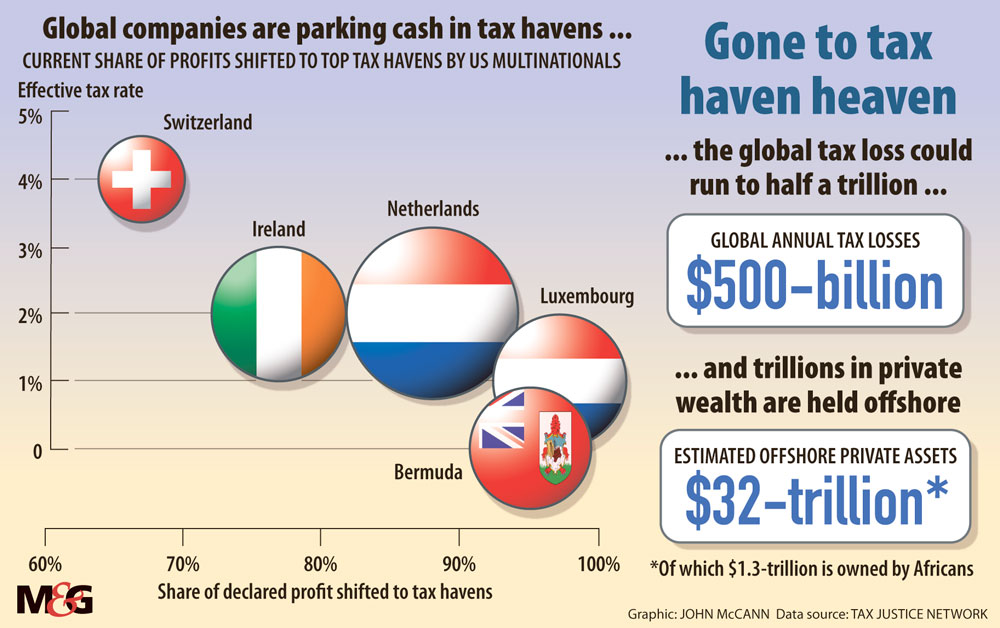

According to the latest estimates of the Tax Justice Network, governments are losing $700-billion a year in taxes because of avoidance by companies and individuals, who funnel their money through low or zero tax jurisdictions — the tax havens.

But more persistent than the leaks themselves are concerted efforts at global tax reform, especially initiatives by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which South Africa and other nations have begun to implement in earnest. So where is the disconnect?

“These leaks bring the underlying issues to life again, and then it all dies down. But the reforms have been happening all along,” said Tim Mertens, the chairperson of the Sovereign Trust, a financial services advisory company.

He and other tax experts say much is being done, describing the uproar over the Paradise leaks as “a bit of a storm in a teacup”.

But George Turner, of the Tax Justice Network, said on the organisation’s website that tax dodging persists and, where it does take place, whether legal or illegal, it is not a victimless crime. “These truly antisocial actions undermine public health and education systems, and drive inequality and corruption, leaving the poorest families and the poorest countries of the world to suffer,” he said.

“Tax Justice Network research confirms that lower-income countries bear a disproportionate share of the burden from global tax abuse — and this has direct costs in terms of everything from foregone economic growth to excess child mortality.”

Various reforms are underway.

The OECD’s Common Reporting Standards have taken effect, which requires countries to obtain information from their financial institutions and automatically exchange it (the scope of which is pre-agreed) with other countries every year. The agreement is based on reciprocity and those who do not provide quality information will be excluded. As of August this year, there were 95 signatories to it, including South Africa. But the initiative has been criticised for not considering or accommodating the needs of developing nations, many of which have not signed up.

Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba, in his mini-budget speech last month, said the first exchanges of information took place at the end of September.

The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting action plan, which is being implemented over the next few years, will also go some way towards stopping companies from abusing complex mechanisms to limit their tax liability in countries where their economic activity took place. Key to this is country-by-country reporting, which will require multinational enterprises to report their economic activity in every jurisdiction in which they are present.

Gigaba said this will begin in South Africa on December 31.

Proponents of the system appear satisfied with the progress and although nonprofit organisations lobbying against tax abuse, such as the Tax Justice Network and Oxfam, have welcomed the reforms, they say it does not go far enough. Chiefly, they claim the reforms do not seek to eradicate the use of tax havens as long as the activity there is legitimate.

“There is no question that some individuals and companies may use tax havens illegally purely to evade tax. This usually involves creating shell companies or letterbox companies with no economic activity in order to hide profits and benefit from lower tax rates than in their true home jurisdiction,” said Louise Vosloo, the lead director of international tax at Deloitte & Touche.

“Nevertheless, tax havens can be used legally in tax planning, where profits are properly attributable to the tax haven and sufficient economic substance is maintained. For example, companies seeking to operate within a tax haven should, in essence, be managed and controlled from that jurisdiction and have sufficient operations that can justify their tax residency.”

Nongovernmental organisations fighting global poverty, such as Christian Aid, argue that all too often there is little to no real economic activity attached to a multinational company’s presence in these jurisdictions.

According to Ernest Mazansky, the director of tax at Werksmans Attorneys, when the likes of Glencore and Standard Bank are found linked to accounts in low-tax jurisdictions (as is the case with the Paradise Papers), “you can bet they had proper tax advice and that these transactions were structured in accordance with the law”.

Judge Dennis Davis, chairperson of the Davis Tax Committee, said it was probably correct to say that the majority named in the Paradise Papers are operating within the law. “If you have 100 South Africans named there, 70 may be legal — but I have no doubt the illegal ones should be there too.”

More radical critics have described tax havens as a scourge that should be eradicated, regardless of whether the transactions are legal. According to an Oxfam policy document, “the consequence is that many economies are pitted against each other as to who can offer the most favourable tax environment to attract foreign direct investment”.

Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has suggested a global minimum corporate tax rate of 20% across the board to effectively deal with tax avoidance.

Mazansky argued that tax havens and secrecy are a thing of the past: “Well, it doesn’t exist the way it did five, 10, 20 years ago. The vast majority of these so-called tax havens — Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, Bermuda — they are highly regulated and highly transparent.

“If you [as a government] want to charge a low tax rate, that is your business; if someone wants to take advantage of it, that is their business.”

Mazansky said the question of secrecy is addressed by the Common Reporting Standards.

The question of whether it is moral and ethical to take advantage of a low tax jurisdiction, even if it is legal, opens up a whole other can of worms, Mazansky said. “If we are talking morality and ethics, then does the taxpayer not have the right to say, ‘Why should I pay tax to an unethical government?’ … As a taxpayer, I can also say I’m not prepared to contribute to that.”

Governments may question the morality of multinationals who exploit tax agreements, as was the case when MPs in the United Kingdom’s House of Commons criticised how the likes of Starbucks, Amazon and Google used a double tax agreement between the UK and Luxembourg.

Double tax agreements are meant to prevent taxation in two jurisdictions but in some cases the agreement is used to pay no tax at all.

Doesn’t this go against the spirit of such an agreement?

Mazansky replied: “If they don’t like it, they can cancel it — at any time they can change it.”

They don’t, however, because it works both ways. “There are people using the UK for exactly the same reason. The UK wants to attract people and draw them in with exactly the same concessions,” Mazansky said.

Authorities follow the leads

The Panama Papers leak of 2016 has had some impact on the world. The Tax Justice Network says, after the leak, 79 countries opened more than 150 inquiries. As of December, authorities had 6 500 taxpayers under investigation and had recouped $110-million in unpaid taxes and asset seizures.

In July this year, the Pakistani Supreme Court removed Nawaz Sharif as prime minister following an investigation linked to the Panama Papers.

Liz Nelson, the network’s director of tax justice and human rights, said the effect on the Panamanian law firm involved, Mossack Fonseca, has been dramatic — partners were arrested, offices were closed and reputations lost.

Ernest Mazansky, head of tax at Werksmans Attorneys, said the leaks led to Panama signing up to the Common Reporting Standards, which it had at first refused to do. Dubai also signed up shortly thereafter.

The South African Revenue Service (Sars) said, from the data retrieved from the Panama Papers, it found 1 917 cases involving South African residents.After removing the duplicates — those who have more than one offshore investment or play more than one role in one or more offshore structures — 1 666 cases remain.

“Thus far 1 290 of the 1 666 South African residents have been matched against the Sars taxpayer register. An overwhelming majority are individual taxpayers. Sars is in the process of verifying the relevant income tax declarations of these affected taxpayers against the Panama data,” Sars said this week.

So far, 814 cases have been “risk profiled”, of which 701 cases meet the risk criteria, which includes under-disclosure or no disclosure of foreign assets or income.

“Of these cases, it became apparent that the offshore structures of 603 of the 701 cases were facilitated by a single South African intermediary,” Sars said.

It is quantifying the tax revenue recovered from the work done on the Panama Papers so far. Sars said it will approach the Paradise Papers in the same manner as it did the Panama Papers. — Lisa Steyn