Kebby Maphatsoe believes some members of the ANC’s NEC may be spies because they ‘use a different language’.

Deputy Minister of Defence and Military Veterans Kebby Maphatsoe has taken some hits in his time, perhaps more hits even than the Daily Sun got on its website for the naked picture of him, apparently snapped by a younger lover in a Cape Town hotel room, which went viral last year.

The paper gleefully described him as the “mapona [naked] minister”.

He has been involved in public spats, including calling former public protector Thuli Madonsela a CIA spy and accusing former intelligence minister Ronnie Kasrils of being a “counterrevolutionary” who had “handpicked” Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo for a honeytrap mission that led to the 2006 rape charges against Jacob Zuma.

Maphatsoe has had to apologise often and, in some instances, put his money where his mouth has led him. In 2016 he paid Kasrils R500 000 to settle a defamation claim following his slurs.

But Maphatsoe is still around, his mouth motoring at 180km an hour to defend Zuma — a man who he says taught him to handle criticism — against all detractors, and working tirelessly for Nxamalala’s ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, to succeed him as president of the ANC.

Last year, the Umkhonto we-Sizwe Military Veterans Association (MKMVA), which Maphatsoe leads, was one of the first ANC structures to proclaim its support for Dlamini-Zuma’s presidential ambitions.

The announcement drew criticism. Ndindeleni Ratshitanga, chairperson of the MKMVA’s Vhembe region in Limpopo, says Maphatsoe had acted prematurely and did not represent the views of structures on the ground. “We, as MKMVA, are not supposed to pronounce on leadership issues before the ANC branches have spoken because we are the vanguard of the revolution and the defenders of the green, black and gold. We must be the last to pronounce.”

Ratshitanga said his region was supporting ANC deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa for the party’s top position.

Maphatsoe further divided MK veterans when the MK Council, which includes struggle luminaries such as General Siphiwe Nyanda, accused him of being re-elected to lead MKMVA at a fraudulent June 2017 conference attended by delegates who had never belonged to the People’s Army.

Maphatsoe says all delegates were accounted for and attributes this criticism to people wanting to “run parallel structures”. He says he has tried, and failed, to bring the MK Council into the fold: “Our differences are generational, not ideological,” he says.

In his home, tucked away in a gated community in Alberton, south of Johannesburg, Maphatsoe dismisses any criticisms as “character assassinations” that emerge “before every ANC conference” in an attempt to discredit him because “I defend President Jacob Zuma”.

Zuma, according to Maphatsoe, has been unduly criticised by “comrades who have a hatred” for the president because they are actually agents of Britain, France and the United States. These countries are concerned about Zuma’s championing of the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) bloc and its repercussions for their own countries and companies, says Maphatsoe.

He describes ANC presidential hopeful Ramaphosa as a “representative of white people” whose “new deal” for the South African economy, which was announced in Soweto this week, merely entrenches Western business interests.

Dlamini-Zuma is the only candidate capable of implementing the “radical economic transformation needed to change the lives of our people”, he says.

The ANC, according to Maphatsoe, has been infiltrated by foreign intelligence forces “to divide us … These people have planted the enemy agents within, to make sure that they destroy the ANC … that is why we have these challenges emerging,” he says. This infiltration has inhibited radical economic policy and hampered the ANC’s ability to deal with unemployment and poverty.

He refuses “to go there” when asked how many of the ANC’s current national executive committee members may be spies “because I don’t want to cast aspersions and say so-and-so is an agent, but I am saying that it worries [us] when NEC members use a different language from the collective”.

And who are the people using a “different language”? Critics of Zuma, including former finance minister Pravin Gordhan, former tourism minister Derek Hanekom and current Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, among others.

An MKMVA leader, who asked to remain anonymous because of ANC protocol, describes Maphatsoe as being driven by self-interest. He says Maphatsoe is demonstrating his political ambitions by defending Zuma and supporting Dlamini-Zuma. “I think he is doing all this for his personal ambition and to secure his government position in the future.”

Ratshitanga describes Maphatsoe as “an intelligent, wise and well-trained MK soldier who, when he wants something, pushes for what he wants. He doesn’t have a point of no return.”

Maphatsoe, whose own branch has nominated Ramaphosa as its presidential choice, says the ANC is weaker today than it was going into the 2007 Polokwane elective conference where Zuma was elected president. The ANC is bereft of political education and is suffering because “most of the branches are not democratic”, he says.

Such is Maphatsoe’s eagerness to underline his struggle credibility — from marching with the students in Soweto on June 16 1976 as a 14-year-old to detailing his first-hand experiences of skirmishes and battles in Angola — that our hour-long interview bleeds into three. He is convivial and engaging throughout.

Born in Soweto on December 31 1962, Maphatsoe says his growing politicisation led to two arrests and subsequent exile in the early 1980s: first to Lesotho, then Zambia and, in 1986, to Angola, where he underwent military training at the Barney Molokoane camp in Malanji. In 1989 he was redeployed to Uganda.

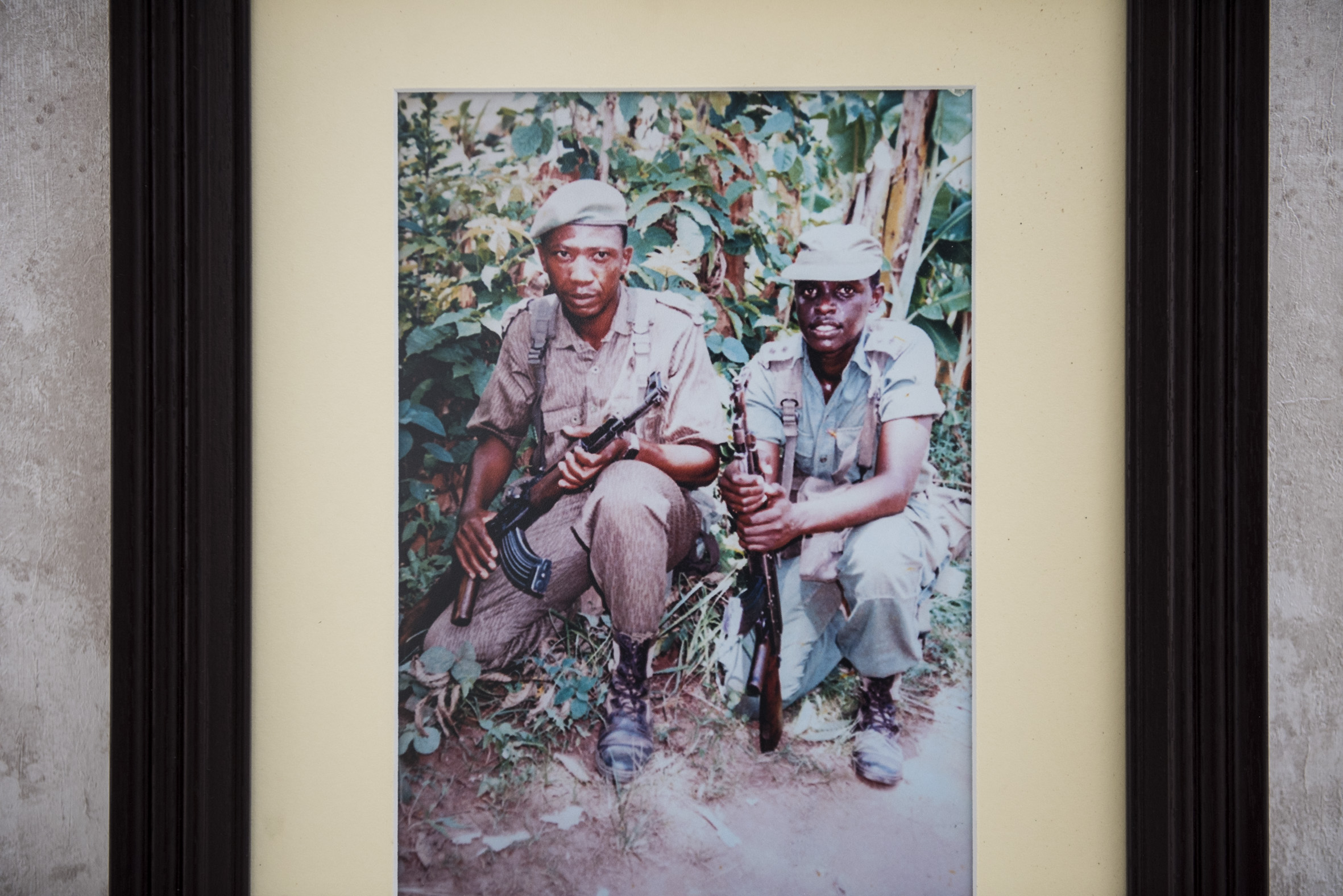

[A young Kebby Maphatsoe (left) during military training. (Delwyn Verasamy)]

There, living conditions were untenable. In a macabre reflection of the Heart of Darkness experiences MK soldiers sometimes faced, Maphatsoe recounts his comrades finding “many remains of human beings, people killed by [former Ugandan dictator] Idi Amin” near their camp.

“Comrades would take the skulls and other remains and sit under the tree and clean them and they would say: ‘This one was beautiful, hey. No, this one was ugly … Some comrades would throw the bones and make prophesies,” says Maphatsoe, describing it as “abnormal behaviour” induced by the pressures of isolation and guerrilla warfare.

The material conditions in Uganda improved, he says, but there were political issues at play, which he refused to describe “unless the ANC gives me permission”. This “political stuff” led to a concern that “we would have a second mutiny”.

So he, together with a group of MK soldiers, left their camp and travelled to Johannesburg in 1991 to tell the ANC leadership about their problems. Heading towards Kenya, they were mistakenly fired on by a Ugandan army patrol, he says.

Maphatsoe was shot in the right arm and bled so heavily that it had to be amputated. He says this mission has been revised to fit the “deserter” narrative that Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema latched on to a few years ago.

Malema described Maphatsoe as a mere “cook” in MK who shot his mouth off more often than he did guns while serving in the People’s Army. Allegations that Maphatsoe deserted MK linger in political circles, and are often used to deride him.

He rails against these accusations: “This is 1991 [when we left Uganda], when the headquarters of MK is right there in Johannesburg. I am deserting? To join whom?” he asks.