Victim of circumstance: Chiman Patel has thrown in the towel amid racial divisions in the province. Photo: Tebogo Letsie

Judging by the recent performance of the rand, you would be forgiven for thinking that there had been no ratings downgrade last week, and that South Africa’s last remaining investment grade rating did not hang by a thread.

In large part, the rand’s buoyancy has been attributed to growing market expectations that the ANC’s elective conference is going to be won by Cyril Ramaphosa, who is seen as market-friendly.

But, analysts say, even if Ramaphosa does win, the markets are underestimating the complexity of the problems facing the economy, which even he will be hard-pressed to fix, and another downgrade is inevitable.

He would also have to ensure that fiscal consolidation and growth-stimulating measures are cemented in the February 2018 budget if there is any hope of preventing the ratings agencies, and most importantly Moody’s, downgrading South Africa further.

Other factors that have nothing to do with South Africa’s dynamics, such as demand for emerging market assets, have helped to support the rand despite the negative news.

After initial weakness off the back of the ratings announcements, the currency rallied in the earlier parts of the week, to levels of R13.69 to the dollar and below.

In the wake of the ratings downgrade, the government has announced additional measures to ensure fiscal consolidation, including efforts to slash spending and raise tax revenues by a collective R80-billion.

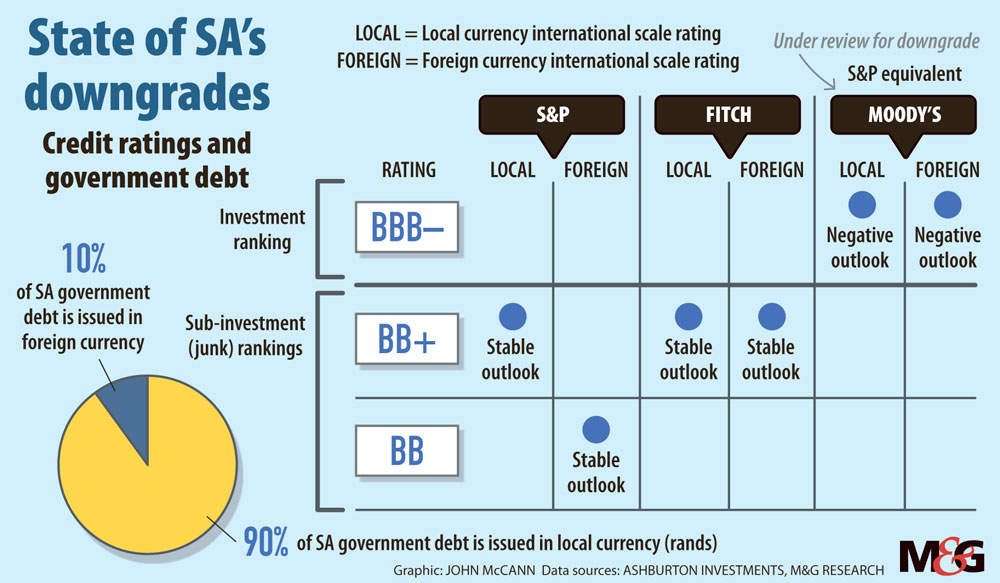

On Friday, S&P Global downgraded South Africa’s local debt to sub-investment grade (junk) status. It had already rated South Africa’s foreign debt as sub-investment but it went a step further, putting the foreign debt a notch further into junk, from BB+ to BB.

Meanwhile, Moody’s placed South Africa on a review for downgrade. It rates both the foreign and local currency debt as one notch above junk.

As a result, South Africa has yet to fall out of the Citibank World Government Bond Index (WGBI). It requires that either S&P or Moody’s must hold a country’s local currency rating at investment grade or an exit from the index is triggered.

About 90% of South Africa’s debt is issued in local currency and the rest is in foreign currency.

Moody’s lead sovereign analyst for South Africa, Zuzana Brixiova, said political uncertainty was key to the country’s inability to tackle low growth and stabilise government finances: “Both low investor confidence and limited progress on structural reforms are rooted in the uncertainty created by the fluid and unpredictable political environment.” She added that this is reflected in the lack of clarity about the government’s fiscal plans.

Moody’s said it would only complete the review once the February 2018 budget had been published, allowing it to factor in the outcomes of the ANC’s elective conference.

“Political developments may provide insights into the direction, content and credibility of the future policy framework,” Brixiova said.

“The review period will therefore also allow Moody’s to take stock of the implications of political developments for key structural reforms that could boost investor confidence in the near term and support higher growth trends over the medium and longer term.”

But even if Ramaphosa does win, a Moody’s downgrade was “almost a given”, said Isaah Mhlanga, an economist at Rand Merchant Bank. There was nothing much he could do to change the financial circumstances of the country before Moody’s 90-day review period closes.

The concerns Moody’s raised had to do with structural growth and fiscal sustainability, he said.

Given the dire state of the country’s finances, there was little that could be done in the short term to turn the ship around, Mhlanga said. There would still need to be a lot of negotiation with business and labour to address these challenges, and talks with labour could be particularly tough, as public sector workers are in the midst of negotiating for a new round of wage increases.

He predicted it is very likely that South Africa will fall out of the WGBI and, as a result, there could be an estimated $10-billion (about R130-billion) capital outflow and a possible hike in bonds yields by as much as 100 basis points.

Policy and political analyst Somadoda Fikeni said there was a general hope that, if Ramaphosa wins at the elective conference, his experience in both the labour movement and business meant he was well positioned to deal with the economy’s challenges.

But the market might not only be misjudging Ramaphosa’s chance of winning, it may also be underestimating the complexity of the deep structural problems the country faces, Fikeni said. These would need more than “just one messianic leader”. It would require an alignment of issues in the party, in the country and in the global economy.

Modern financial markets often operate on sentiment rather than fact, he said, adding that the currency’s improved performance was also a result of other factors. Whatever the outcome of the conference, the market could be growing more positive because of the groundswell against state capture, and especially because the judiciary, which has proven itself to be independent, has taken up a number of cases on the matter.

There might also be the feeling that any new leadership would be better than the present, particularly for policy certainty and cohesion, Fikeni added.

But global factors also affect the currency’s performance, including the continued attractiveness of emerging market assets, which has supported investment flows into South Africa.

Econometrix director Azar Jammine said the rand’s reaction showed foreign investors are only too keen to buy the currency at levels they see as very cheap. Currently the global economic environment is very positive and there is an appetite for risk, he said.

But if this was to change, the converse would be true, he added. Following the firing of finance minister Nhlanhla Nene in December 2015, the rand almost reached R17 to the dollar.

Although the politics of the time was important, global conditions, including plummeting commodity prices and panic over commodity linked currencies, had a major effect on the rand, Jammine said. “Politics do play a role but they are not the only factor.”

But there was some data to suggest that not every area of the economy was in dire straits, said Jammine, referring to recent growth in retail sales, which rose 5.4%, year on year.

Izak Odendaal, an investment strategist at Old Mutual Multi-Managers, said, even considering the measures announced by the government this week, until there were firm policy commitments in place, particularly in the 2018 budget, they would not carry much weight with the ratings agencies.

He agreed that, even if Ramaphosa does win in December, he could not put concrete measures in place in time, adding that South Africa’s ratings, especially by Moody’s, would still be at risk.

Moody’s gave an explicit warning that, besides fiscal consolidation measures, it wanted to see policies implemented aimed at encouraging economic growth, Odendaal said.

“In the absence of measures that will really stimulate economic growth, really harsh spending cuts might be counterproductive and the ratings agencies might view this as negative,” he said.

Ramaphosa’s new deal wins support

ANC branches in three provinces have put forward their preferred candidate to lead the party.

The Northern Cape and the Western Cape will back Cyril Ramaphosa. The Free State has backed Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, although the nomination appears to have been nullified by a court challenge that succeeded on Wednesday.

Zamani Saul, the provincial secretary for the ANC in the Northern Cape, said the focus was on the overarching ANC policy on economic transformation and not on the various contenders.

But Faiez Jacobs, the Western Cape secretary, said Ramaphosa’s economic vision had played a key role in the province’s choice.

“From a Western Cape point of view, and considering the overwhelming mandate of our branches, we must point out that, whilst NDZ [Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma] is talking the ANC economic policy talk, the very obvious reason for supporting Ramaphosa’s new deal is that he is determined to root out corruption, to put a stop to state capture and hold to account those who have made themselves guilty of looting the public purse,” he said.

The new deal is not new in terms of policy but it clearly spells out what Ramaphosa will do immediately if elected ANC president.

“Radical economic transformation [RET] must address inequality, unemployment, poverty and the concentrated pattern of economic ownership,” Jacobs said.

“ANC leaders must not use RET as a guise for looting … We want accelerated change of ownership but not only a replacement of whites with [a] few new politically connected black elites.”

In particular, the ANC Western Cape supports the new deal’s emphasis on land reform, job creation and enterprise development to get the country out of the economic doldrums it finds itself in.

The province also strongly backs a collaborative approach to fixing the country’s economic problems, which is spelled out in the new deal, he said.

The province’s choice of candidate was also driven by concerns that the ANC is at risk of losing the 2019 national elections.

As such, “Cyril Ramaphosa is a leader who can be trusted and who inspires confidence as a result of his track record,” Jacobs said. — Lisa Steyn